Through the woods

The calendar presses on our shoulders and breathes down our necks, as hard to evade as a lap-seeking, too-hairy cat who won’t take no for an answer. Progress escapes us in our habitual surroundings. But a change of scene can help, letting concentration in and familiar domestic distraction out through the scathole. So, pursued by deadlines, E and I fled uphill towards a working getaway for the weekend.

The calendar presses on our shoulders and breathes down our necks, as hard to evade as a lap-seeking, too-hairy cat who won’t take no for an answer. Progress escapes us in our habitual surroundings. But a change of scene can help, letting concentration in and familiar domestic distraction out through the scathole. So, pursued by deadlines, E and I fled uphill towards a working getaway for the weekend.

On the way we sped through the state’s last fifteen minutes of winter (above, snow and pines above the Rim). And we eyed the sacred, cloud-shawled San Francisco peaks above golden grasslands << before landing in our digs, a comfy set-up in a hotel with a good restaurant in a plain-faced old Arizona town.

We were bound to get something done: it was raining and there were few distractions. It’s not that there’s nothing to see around  here — there’s a big hole in the ground made by a hurtling chunk of space rock, ancient homes whose stones stud the hills and whose builders’ descendants still live nearby, and an entire forest that petrified where it fell.

here — there’s a big hole in the ground made by a hurtling chunk of space rock, ancient homes whose stones stud the hills and whose builders’ descendants still live nearby, and an entire forest that petrified where it fell.

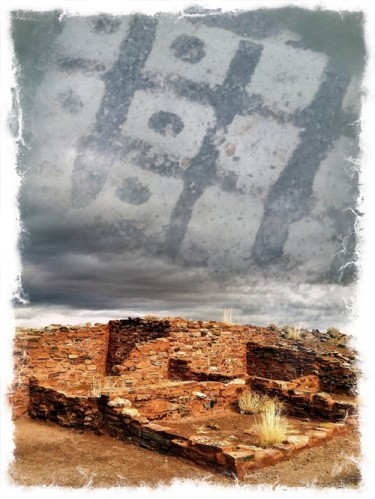

<< Homol’ovi State Park, Pueblo #2 with a painted pot sherd superimposed on the stormy sky.

But for tourists interested in more than just “standin’ on the corner”, the main attraction of the old town is the grand hotel we’re staying in: La Posada sits on the rail line, so there are intermittent trains to ogle on the BNSF’s Seligman sub (supposedly up to 70 a day!), and occasionally they whistle or croak as they pass, like the ravens lodged in the high tops of leafless cottonwoods on the hotel grounds. The gardens must be beautiful in warm months, but on Saturday its sodden hay-bale labyrinth looked dreary in drizzle and mud.

The building itself is a labyrinth, but not at all dreary. It is a labor of love layered by laboring love — two stories of imagination, design, and money lavished on the last Fred Harvey Company railway hotel: the first time from the ground up by architect Mary Colter during the original construction — stuffed full of furniture and curios as if the resident ravens had plundered the continents in their forays; and the second time from the inside out by its current owners who are still restoring it in the spirit of Colter’s ambitious fantasy. It’s a daunting effort, cleaning up and re-constructing the huge building after a couple of decades of use and abuse as the Santa Fe railroad division

design, and money lavished on the last Fred Harvey Company railway hotel: the first time from the ground up by architect Mary Colter during the original construction — stuffed full of furniture and curios as if the resident ravens had plundered the continents in their forays; and the second time from the inside out by its current owners who are still restoring it in the spirit of Colter’s ambitious fantasy. It’s a daunting effort, cleaning up and re-constructing the huge building after a couple of decades of use and abuse as the Santa Fe railroad division  offices, when it was gutted, divided into cubicles and otherwise desecrated. Here’s a historic photo of the “Ball Room” during the office days above a photo of its current manifestation.>> The ceilings tell the whole story: one, a hideous lowered acoustic tiled, fluorescent-fixtured horror, the other a lofty arched and painted heaven.

offices, when it was gutted, divided into cubicles and otherwise desecrated. Here’s a historic photo of the “Ball Room” during the office days above a photo of its current manifestation.>> The ceilings tell the whole story: one, a hideous lowered acoustic tiled, fluorescent-fixtured horror, the other a lofty arched and painted heaven.

There’s plenty of distraction in exploring the details and contents of the building, a work-in-progress for the restorers, but the calendar still lurks in the corner of our eyes, waiting to pounce, and E and I return to the room between walkabouts to push forward our own work in progress.

a detail of the ballroom’s turquoise corbels and copper designs on the rafters>>

The Mystery of the One-armed Bandit and other Tales of the Cold War

Just a few days ago, we experienced a rare deep-freeze in the Southwest deserts. During a normal winter it can get cold in the low desert — not Canada cold, or even Iowa cold, of course — but this was an unusually lengthy and deep cold for our desert, sinking well below freezing for several nights running, and not warming up past the mid-40s during the day. One spot in our yard went below 20F for three nights in a row. That’s enough to cause trauma and die-back even in hardy native plants. Birds spend long daylight hours feeding frantically at both natural and human-provided food sources; mammals, too, unless they’re equipped to shelter in cavities, crevices, or caves, or underground like the local reptiles and arthropods.

One spot in our yard went below 20F for three nights in a row. That’s enough to cause trauma and die-back even in hardy native plants. Birds spend long daylight hours feeding frantically at both natural and human-provided food sources; mammals, too, unless they’re equipped to shelter in cavities, crevices, or caves, or underground like the local reptiles and arthropods.

<< Old-school thermometer hung in a young saguaro in the cold part of our yard

Cold-powered hunger also can make animals “tame” — fearless hummingbirds slurp at feeders as they’re being carried out to the trees, and aloof night-time hunters like owls and coyotes will boldly stretch their workdays into sunlit hours, and onto back porches and front yards. This boldness can increase success in finding nourishment, but it also increases exposure, which can be risky for animals who rely on not being seen for both safety and effective foraging. Traveling in California during an extreme coldsnap many years ago, E and I saw three bobcats in a week, because the stealthy nocturnal predators were out in daylight hours hunting sparrows and small mammals themselves made unusually unwary by the desperation of hunger.

But a mitigating feature of desert freezes is how quickly warmth follows cold. There’s no lengthy spring warm-up. Within a day or two of our arctic chill, daytime temps have already bounced up to the 70s, 10F degrees above the seasonal average. Expert survivalists don’t waste this advantage: as soon as the sun can warm air and soil again and melt pools and trickles, animals re-appear in search of food. This morning I spotted a coyote foraging in the neighbors’ front yard in broad daylight. After a cold snap, temperatures may rebound quickly, but cold leaves many animals hungrier than usual, and without whichever of their plant or small-animal food resources that succumbed to the cold. In the days and weeks afterwards, sometimes extraordinary tactics are required for survival.

in search of food. This morning I spotted a coyote foraging in the neighbors’ front yard in broad daylight. After a cold snap, temperatures may rebound quickly, but cold leaves many animals hungrier than usual, and without whichever of their plant or small-animal food resources that succumbed to the cold. In the days and weeks afterwards, sometimes extraordinary tactics are required for survival.

>> An aloe blossom that survived, and a female Lesser Goldfinch who didn’t (photo A.Shock)

That might explain E‘s sighting of a Stripe-tailed scorpion (Hoffmannius/Væjovis spinigerus) scuttling about on our driveway the other evening at sunset. We seldom see scorpions moving around in our yard — believe me, I’ve tried, black-light and all. Sadly, most of our encounters with these efficient nocturnal predators are with drowning victims in the pool. And NEVER in winter — they seek shelter as soon as the weather gets cold, and don’t reappear until it’s balmy again. For an exothermic organism, there’s no point in being out and about in the cold, expending energy at a time when their arthropod prey is hibernating, making it hard to recover the calories lost in fruitless hunting.

Yet, here was a striper in our driveway. Maybe it was forced by the cold to come out to try for a m eal to boost its caloric resources so it could survive the rest of its hibernation. Maybe its lack of left-hand grasping pincer meant it had gone into winter with fewer reserves under its exoskeleton. What its story is we’ll never know for sure. But my hunch is that our efforts at salvaging succulents contributed to its untimely emergence. We had stashed most of E’s tender cactus and succulents in the garage when the temps plunged. Maybe this guy was wintering in a planter, and tempted by the relatively warm dark of the garage, wandered out trying to steal a march on spring. E snapped a couple pix for me, and let it go on its way, to whatever resolution it could manage.

eal to boost its caloric resources so it could survive the rest of its hibernation. Maybe its lack of left-hand grasping pincer meant it had gone into winter with fewer reserves under its exoskeleton. What its story is we’ll never know for sure. But my hunch is that our efforts at salvaging succulents contributed to its untimely emergence. We had stashed most of E’s tender cactus and succulents in the garage when the temps plunged. Maybe this guy was wintering in a planter, and tempted by the relatively warm dark of the garage, wandered out trying to steal a march on spring. E snapped a couple pix for me, and let it go on its way, to whatever resolution it could manage.

Good luck to it in its wanderings to find dinner and a new refuge. But I wonder what that hunger sharpened coyote was rummaging for so hopefully across the street “after hours” this morning? Sometimes it’s the late bird that gets the worm.