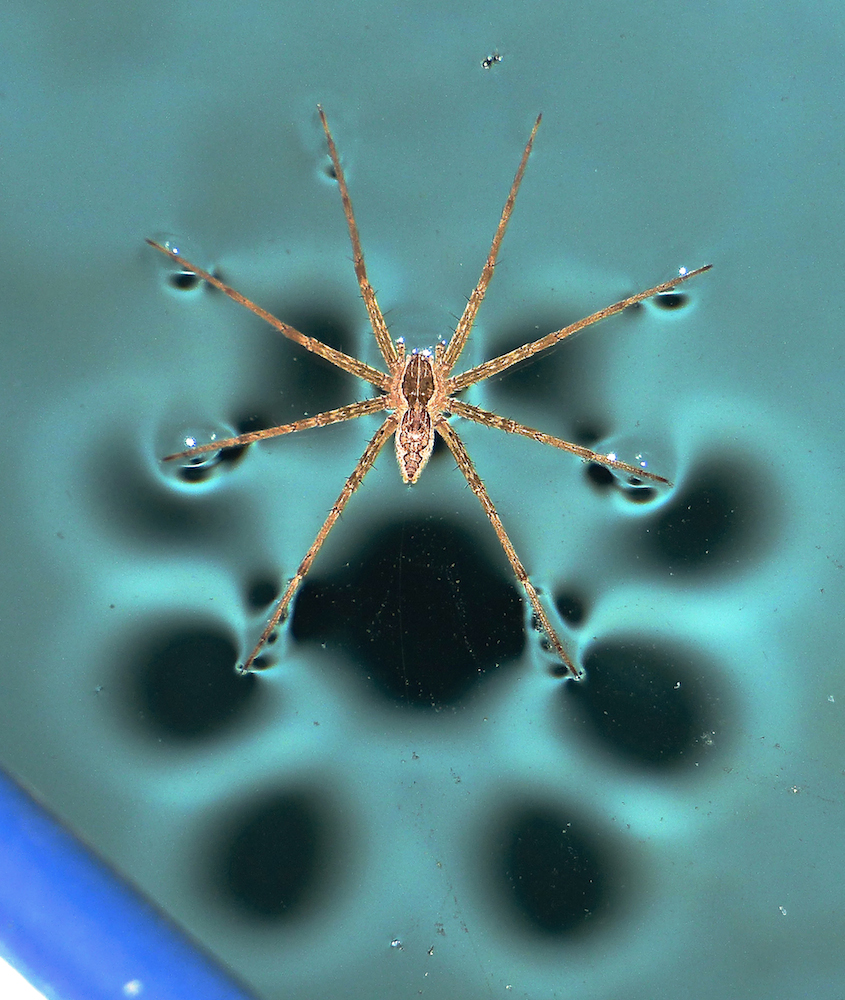

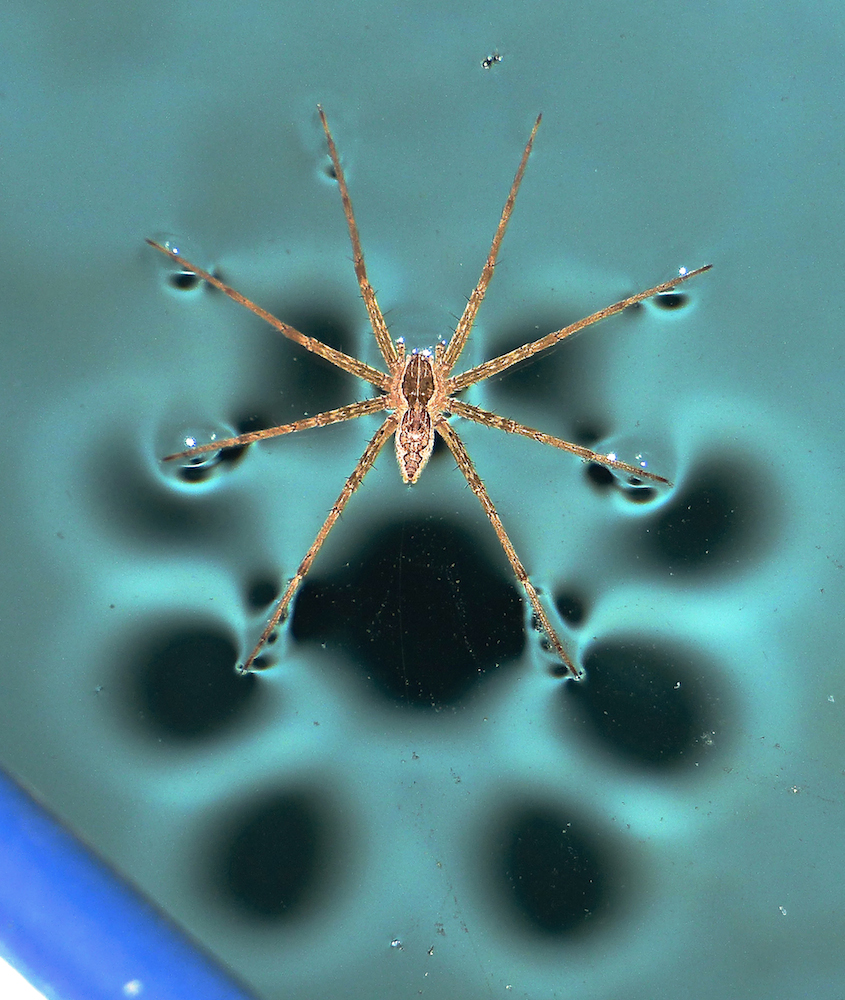

IMPORTANT UPDATE: The internet is full of mis-identified things, and I don’t wish to add to them. I’d like to correct my original mis-identification of the large fishing spiders who share our pool. They are Nursery-web spiders, Tinus peregrinus, and NOT Six-spotted. Happy to have had an expert’s id on this amazing arachnid.

The largish Six-Spotted Fishing Spider who took up residence in our swimming pool this summer has been missing for a couple of days. For the past two nights, I’ve gone out with a flashlight to look for him with no success, running the beam along the cracked tile edges and around the cement block angled on the top step for accidental swimmers to find a way out. I joked with E that maybe a lady fishing spider had found him to her liking.

But it turned out that was no joke. Tonight when I searched, there he was — lurking above the water on the side of the block ramp just like the last time I’d seen him. Then, looking more closely, I saw too many legs, and not in a good way. It seems the Cap’n had met his First Mate, who was also his last. His body was limp, hanging upside down from her grasp, or at least tangled in her limbs. I’m not an arachnid expert, it was dark and beginning to rain, and details were hard to make out. But here’s a photo (if you’re brave you can click on it to enlarge):

>> Fishing spiders in our pool. One of them is enjoying a little post-date predation. (Photo A.Shock)

Certain species of Fishing spiders are known for their male’s “self-sacrificing” mating habits, and that’s how I’m interpreting this poolside homicide. I suppose it could have also been a territorial dispute — I’ll never know. But if the “last supper” theory is correct, the lady is now gravid, perhaps explaining the gleam in her eye. (Actually, the tiny reflective gleam that’s visible if you enlarge the photo is my flashlight reflecting back from one of her retinas, like a cat’s eye in the dark).

Here’s some colorful literature on the “obligate death” scene of a Nebraska cousin (Dolomedes tenebrosus).

Swimming after dark in our pool is currently an adventure, because we’re not the only ones in the water. The local Coast Guard makes frequent forays across the shipping lanes, issuing from his snug berth in a cavity between the edge-tiles at the shallow end.

Here is the Coast Guard himself:

He’s a sizable male Six-Spotted Fishing Spider (Dolomedes triton, photo A.Shock). We think he’s male because of his trim abdomen and long leg-to-body ratio. And sizable as in “would-sit-on-the-palm-of-your-hand-with-only-a-little-to-spare.”

We’ve always had these handsome but intimidating spiders living around our pool — one, sometimes two at a time, each at opposite ends — holed up during the day and visible only as hair-thin leg-ends curled subtly around the edge of a cracked tile inches above the water. At night, however, they hunt, either hanging by their back legs with their sensitive front legs spread across the water, waiting for a surface-trapped insect to struggle by, or by speedily skittering across the taut surface, gleaning the day’s “tar-pit” casualties.

Fishing spiders are intensely aquatic, and will catch and eat anything they can subdue, including small fish — an item not on the menu in our pool, but there’s plenty of small invertebrates to feast on. The Coast Guard clearly finds plenty of nourishment: he’s grown quickly since we first noticed him earlier in the warm season.

Six-spotted Fishing Spiders are common water-side natives of Arizona and much of the United States. And in case you’re wondering, his eponymous spots are on the underside of his cephalothorax, but I’m not flipping him over to count!

Close-up of a Sphinx Moth caterpillar. Green. Giant. Loves chile plants. (photo A.Shock)

Fall is a second spring in the desert, and things are wandering.

Immature but already full-grown birds hatched this year are making their first migration, or seeking a permanent residence away from the parental sphere. Young mammals, too, are moving to new locations on their own. Some creatures are fanning out looking for mates, such as tarantulas (right) and other arthropods.

Although many make it, this can be a perilous diaspora, and it brings visibly increased mortality along roads as young inexperienced animals or adults driven by an impulse stronger than their understanding of speeding vehicles try to cross busy highways.

In our yard the main hazard — other numberswiki.com

than waiting predators — is the swimming pool. The male sunspider below (possibly Eremochelis bilobatus) fell into the pool sometime during a nocturnal rambling and couldn’t get out. With luck, he’d found a female before he succumbed, and was able to do his part to continue the local population.

People often ask how big they are, so I’ve included my hand for scale. (Click to enlarge to see his bristly glory and fierce mandibles. Both photos, A.Shock). Driven to find out more about Solpugids or sunspiders? Check this website. For the record, taxonomists consider them more closely related to Pseudoscorpions than to spiders.

I haven’t been posting here much recently, due to circumstances.

Circumstances like deadlines, ants, and the fact that I may be about to lose the entire file structure of my photos on the computer as a result of trying to solve the problem of a broken DVD player (a chain of events as obtuse as it sounds) — all the standard impediments to writing. So instead of shrieking, I choose to post this photo of an excellent organism we saw yesterday in the skirts of the Pinal Mountains:

You can tell by its spectacular comb-like antennæ that it’s a moth — the imago of a Grapeleaf Skeletonizer (Harrisina sp.). In this adult format, the metallic blue moth is harmless enough, here sipping nectar from a milkweed flower. It will only live a few days, which it will spend mating and laying eggs, which will hatch into beautiful caterpillars that will efficiently denude plants like grapes and virginia creepers of their foliage. Meanwhile, it wants you and any other looming predators to think it’s a wasp and leave it alone — a strategy that works pretty well, until you notice those telltale pectinate antennæ, a dead giveaway for mothliness.

(Photo A.Shock)

The New Camera has enabled me to take shots that the beloved, well-used but limited Old Camera couldn’t handle. Both are pretty good at macro, but zoom is the strength of the new camera. Effective zoom has made it possible for me to get a shot of something I’ve wanted to capture for a long time: the lovely paper wasps who float like little golden sea-planes on the surface of the pool.

Above, Paper Wasp afloat: no pontoons needed — its light body weight, waxy coating, and ability to create floatation cushions under its feet by not breaking surface tension, enable it to bob on the water while it collects mouthfuls to build with — you can see from the surface distortion in the photo above that this wasp has its mouthparts on the water, actively taking it in. Once it’s tanked up, the insect will rise nearly vertically off the surface to fly back to the nest. They almost never swamp, even in the chop I make swimming laps.

These golden sea-planes are Polistes wasps, commonly called Paper Wasps because of the papery, multi-cellular nests they build. Ours are probably Polistes flavus, but I’d need confirmation from someone who knows more about wasps than I do, to be certain. They seem to be peaceable sorts, and tolerate us moving around their space. In our experience, they’ve never acted aggressively, even once when E was tugging up the dead lemon grass where unbeknownst they’d built their nest. A few of them flew up and out of the fibrous clump. He scampered away, but there was no trouble — none of them even bothered to escort him away from the scene. Paper wasps are good for a garden: the adults drink plant nectar (and hummingbird food) for their own nutrition, but they are tireless predators of small voracious caterpillars and other soft-bodied insects which they prepare by chewing and deliver as food balls to their young waspy larvæ.

These golden sea-planes are Polistes wasps, commonly called Paper Wasps because of the papery, multi-cellular nests they build. Ours are probably Polistes flavus, but I’d need confirmation from someone who knows more about wasps than I do, to be certain. They seem to be peaceable sorts, and tolerate us moving around their space. In our experience, they’ve never acted aggressively, even once when E was tugging up the dead lemon grass where unbeknownst they’d built their nest. A few of them flew up and out of the fibrous clump. He scampered away, but there was no trouble — none of them even bothered to escort him away from the scene. Paper wasps are good for a garden: the adults drink plant nectar (and hummingbird food) for their own nutrition, but they are tireless predators of small voracious caterpillars and other soft-bodied insects which they prepare by chewing and deliver as food balls to their young waspy larvæ.

(Both photos A.Shock — Do click to enlarge, especially the upper one. There’s lots of good detail to be gained, like sparly water drops on its abdomen.)

<< The last post was a photo-op provided by the death of a Tiger Whiptail by drowning. But today I saw the tiniest slip of a whiptail — maybe fresh from the egg — snapping up ants on the back porch. Life goes on.

<< The last post was a photo-op provided by the death of a Tiger Whiptail by drowning. But today I saw the tiniest slip of a whiptail — maybe fresh from the egg — snapping up ants on the back porch. Life goes on.

This morning, when I opened the pool skimmer basket, a female Palo Verde Root Borer Beetle more than three inches long was swirling around inside, caught in the suction whirlpool. She looked defunct. I fished her out, arrayed her on a large ammonite fossil, and took some macro shots. Just as I was finishing up a couple of her feet started flexing and waving. These are very tough creatures: this isn’t the first time moribund subjects have resurrected during a photo session. I put her in a sheltered place to recover or to complete her expiration and fulfill the local ants’ devotion to energetic thrift. I recently read that although the robust and destructive larvæ of this beetle can live underground for several years chewing on tree roots like Niddhog gnaws Yggdrasil, the adult beetle will only live the span of a single monsoon season. It’s entire purpose is to mate, fertilize or lay eggs, and die.

Here’s a raccoon’s-eye view of her (all photos A.Shock):

When I checked again later, she was gone. I’m not sure what scavengers are abroad in daylight hours who are large enough to nab her — the foxes and raccoons won’t come out until after dark, so maybe she revived and crawled away

When I checked again later, she was gone. I’m not sure what scavengers are abroad in daylight hours who are large enough to nab her — the foxes and raccoons won’t come out until after dark, so maybe she revived and crawled away  to burrow down into the soil to lay her eggs. Here’s a foot on the second pair of legs, like a grappling hook. These sticky hook-feet come in handy since the beetle’s favored method of travel is to bomb around through the moist monsoon air until it hits something, then cling. If one hits your face, it hurts, even though they generally just bounce off. >>

to burrow down into the soil to lay her eggs. Here’s a foot on the second pair of legs, like a grappling hook. These sticky hook-feet come in handy since the beetle’s favored method of travel is to bomb around through the moist monsoon air until it hits something, then cling. If one hits your face, it hurts, even though they generally just bounce off. >>

Finally, below is an image I posted here previously called “Convergent Evolution”. This is the other “drowning victim” I mentioned earlier, the one who fully revived as I was photographing her (see the blurry foot? That was just the first indication). The pinchy mouthparts have nothing to do with eating. They are for battle — males use them to vanquish competitors, and to subdue females. The larva does all the feeding for this species. How much does that animal look like a pair of pliers? Clearly convergent evolution.

Robo-fly or Robber fly? This handsome ærial predator was basking on the parsley in the garden this morning. I’m armed with a new camera, just getting acquainted, and marauding for likely subjects. Still learning — in fact, I hadn’t figured out how to shoot in Macro mode at this point, but the standard shooting mode digitally cropped for a zoom did a fair job. It’s hard to see, but I believe this bird has lunch in its mouthparts; I spy extra wings under the crook of that front leg. And check out the grappling-hook feet!

Robber fly, family Asilidae (photo A.Shock)

It’s squishy and voluminous, bulbous-headed and bulgy. Plus, it engulfed every single leaf of a poor little potted chile, covering the soil below with drifts of black frass, but… it’s REALLY GREEN, and I think it’s pretty spectacular, in its way. It’s a hornworm — I’m not sure which — which makes it the larva of one of the Sphinx moths. Two days after I took this photo (do click to enlarge, I loaded a file as monstrously huge as this caterpillar is), it disappeared: it must have plopped to the ground below the plant to bury itself a few inches down in the soil to pupate. Then it will emerge as a moth. I’m trying to imagine what it looks like when a full-grown sphinx moth — a creature of the night air — emerges from dirt. Imagine!

Check the sparse, sparkly polyester-looking hairs on its back, the bristles on the “feet” of its fleshy, blunt prolegs. And the golden “portholes”. What a machine! We’re watering the now leafless chile plant, hoping the frass dissolves and the plant can re-process the nutrients from its own devoured, caterpillar-bypassed leaves to grow more. (Photo A.Shock)