A few days ago, we drove far out into sage-covered lava rocks to check out some hot springs on the east side of the Sierra Nevada. After walking to the top of the hill, walking around the next hill and between two other hills, seeing what birds were around and  about, and while E was nearby doing Science in Hot Water, I felt I’d had enough wind — since we were above 7000′ feet, it was a cold wind — so I sheltered in the cab of the truck.

about, and while E was nearby doing Science in Hot Water, I felt I’d had enough wind — since we were above 7000′ feet, it was a cold wind — so I sheltered in the cab of the truck.

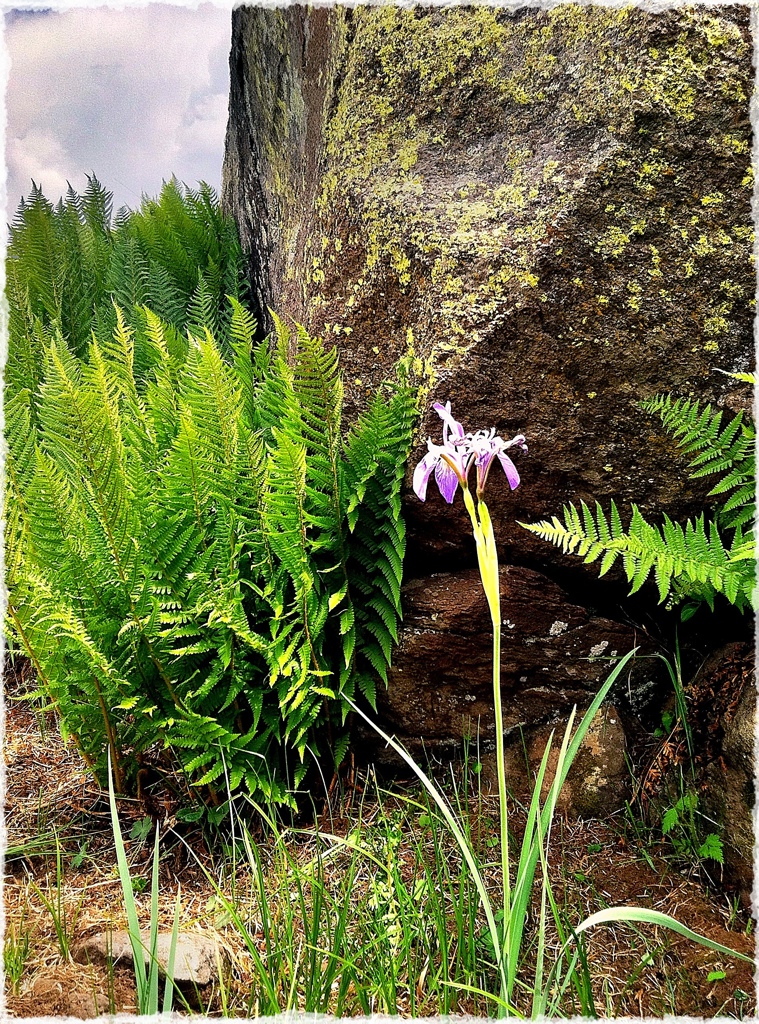

The rock I watched >>

If this seems like a nature-phobic sort of thing to do, let me recommend it: a vehicle makes a wonderful blind, great for observing otherwise human-wary wildlife. I watched a Wilson’s warbler, a sweet scrap of yellow with a smart black cap, struggle in the gusts from one juniper tree to another right in front of the hood; an Audubon’s warbler, too, was getting buffeted about in the same nearby trees. And, next to the truck was this large Rock (top photo). I studied it, thinking about making a sketch.

truck was this large Rock (top photo). I studied it, thinking about making a sketch.

<< Ground squirrel and spiny lizard (far right edge of rock)

It was clear that this rock had been heavily used — most obviously by people, who’d built fires under it, but also by plants who’d sprouted in its cracks, lichens crusting its surfaces, and by animals, who were sunning themselves on it.  Although I never made a sketch, I was able to watch and photo a series of species — seven in all, ultimately, although I only could photo five — as they used this rock as viewpoint, shelter, sunning place, food storage or source. (All photos A.Shock; be sure to click on each image to enlarge for better viewing.)

Although I never made a sketch, I was able to watch and photo a series of species — seven in all, ultimately, although I only could photo five — as they used this rock as viewpoint, shelter, sunning place, food storage or source. (All photos A.Shock; be sure to click on each image to enlarge for better viewing.)

Birds landed on it briefly, including the Wilson’s warbler, and a vivid Western tanager male.

<< male Western tanager on the Rock

Being hydrothermally altered (so I’m assured by E), it was porous and full of useful cracks and refuges. A small movement caught my eye, and in the darkest crack in the darkest center of the sooty overhang, a Piñon deermouse  had packed the crevice with soft needles and moss, and was turning this way and that in its snug, sheltered nest, running tiny paws over its big ears.

had packed the crevice with soft needles and moss, and was turning this way and that in its snug, sheltered nest, running tiny paws over its big ears.

<< Piñon deermouse in crevice nest in the Rock

Best yet, I happened to look over at the upper dark hole in the rock just in time to see this little face peering out, checking on how things were in the middle of the day. It’s a Long-tailed weasel, a native here (unlike in New Zealand), but still an active and industrious predator. I was alarmed when the ground squirrel above made a short trip into the very hole the weasel had just gone back inside. But there was no disaster, and the squirrel came right back out again, presumably with all its parts, and with no dramatic nature-show confrontation music to mark the event.

came right back out again, presumably with all its parts, and with no dramatic nature-show confrontation music to mark the event.

Long-tailed weasel outside its hole in the Rock >>

The seventh species I observed on the Rock was Homo sapiens. It was one of the two dudes that came by in a battered Isuzu Trooper (like the one I drove for years). Although I didn’t get a picture of him up on the top of the Rock, we were particularly glad to see this human being: something you won’t often hear me say. The reason he was a fine sight on this backcountry, rocky road? That’s another story. I won’t tell it here, except to say that it involved jumper cables…