The Ganskopf Collection: Epilogue

(This is the FINAL final episode, the Epilogue to an eight part series. To read all the episodes, click here: The Ganskopf Incident or on The Ganskopf Incident category in the sidebar to the left. The earliest posts are at the bottom, scroll down to read them chronologically from the bottom up.)

(This is the FINAL final episode, the Epilogue to an eight part series. To read all the episodes, click here: The Ganskopf Incident or on The Ganskopf Incident category in the sidebar to the left. The earliest posts are at the bottom, scroll down to read them chronologically from the bottom up.)

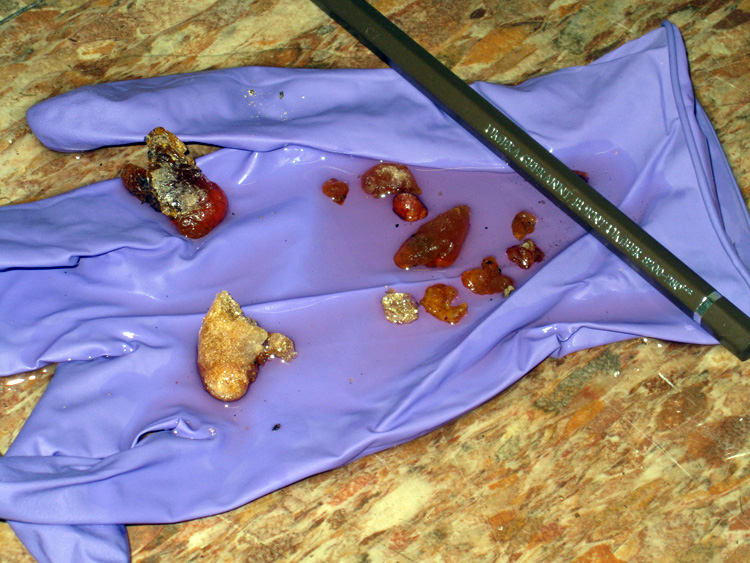

“That’s what conservation departments are for.”

That remark by Dr. Danneru stayed with me a long time, quite as long as the shock of seeing the fragile amber “fetish” destroyed by infinitesimally improbable misfortune and scofflaw beverage consumption. His controlled tone was either supremely insensitive or genuinely kind: either a willful effort to deny the magnitude of the loss, or a desperate reassurance intended to put things in perspective for us. I’ve never been able to decide which. Coming from the person most responsible for the disaster, it was certainly self-serving.

a long time, quite as long as the shock of seeing the fragile amber “fetish” destroyed by infinitesimally improbable misfortune and scofflaw beverage consumption. His controlled tone was either supremely insensitive or genuinely kind: either a willful effort to deny the magnitude of the loss, or a desperate reassurance intended to put things in perspective for us. I’ve never been able to decide which. Coming from the person most responsible for the disaster, it was certainly self-serving.

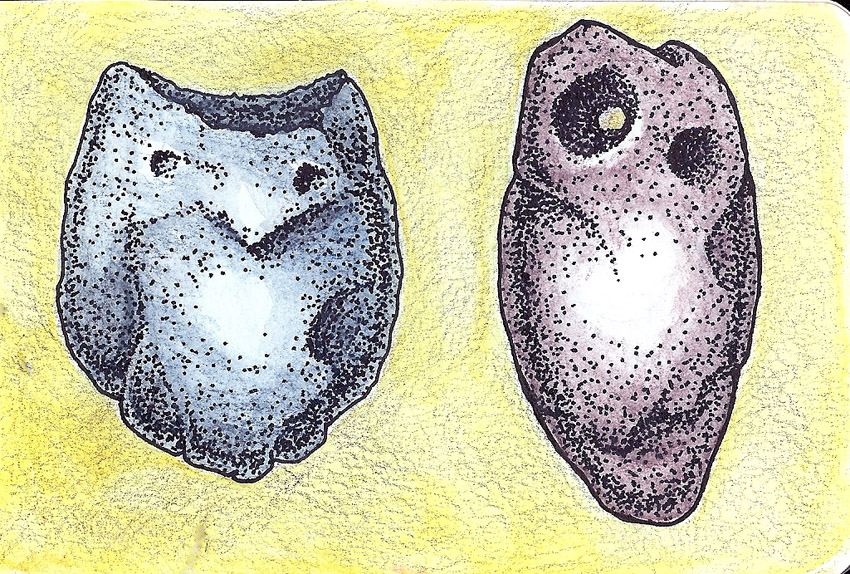

In any case, the statement was mere bravado – the piece was unrecoverable, as he must have known. My stained, smeared drawing of it was used as evidence in the insurance inquiry and subsequent lawsuit, and I had to return to Lassiter for a day in court where I answered a lot of questions asked by precisely-speaking men in expensive suits. Surprisingly, the question of tea never came up. Apparently ranks had been closed in the face of investigation, perhaps agreements reached. Museums, collectors, academia, and the legal profession are a squabbling ménage, yet they perennially cohabit, with law enforcement and insurance their prying neighbors, ears pressed hard to the walls.

where I answered a lot of questions asked by precisely-speaking men in expensive suits. Surprisingly, the question of tea never came up. Apparently ranks had been closed in the face of investigation, perhaps agreements reached. Museums, collectors, academia, and the legal profession are a squabbling ménage, yet they perennially cohabit, with law enforcement and insurance their prying neighbors, ears pressed hard to the walls.

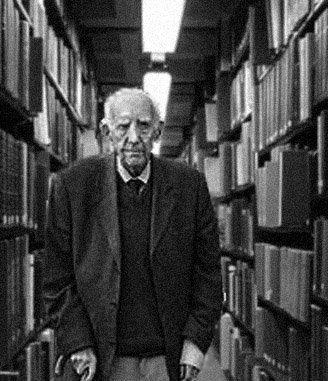

I never heard the outcome of the case, but I was fascinated to hear that the monetary figure in question – the insured value of the shattered piece – was put at an amount well above what I could earn in a year. This official valuation had been provided by an unexpected expert witness: Dr. Darius Danneru, PhD, MacCormack University, member ESSA, ICER, fellow of the Szeringka Institute, etc etc, who, it seemed to me, was hardly impartial in the matter but who turned out to be the world’s leading expert on the subject, which explains a lot.

MacCormack University, member ESSA, ICER, fellow of the Szeringka Institute, etc etc, who, it seemed to me, was hardly impartial in the matter but who turned out to be the world’s leading expert on the subject, which explains a lot.

Except for a final payment for the straw owls drawing, I never heard from Dr. Harrower again, or went back to the Ganskopf Collection to draw. I don’t know if this was because the project was finished anyway, or if it ended precipitously as a result of the calamitous mishap. There had been dialog between us concerning the drawing of the archaic stone owls, which Dr. Harrower insisted he hadn’t requested, and so did not intend to pay for. Rather than pressing for payment, I called him to ask for the drawing back. In a refined Texas drawl, he politely agreed to send it, but the only thing the mail ever brought was an apology from him with a message that he seemed to have misplaced the drawing. I let it drop at that.

him with a message that he seemed to have misplaced the drawing. I let it drop at that.

My other drawings of owl “fetishes” eventually appeared (without credit, to my astonishment and irritation) in a popular archæology magazine – a news stand “glossy” – accompanying a fluffy article about mystery artifacts by Dr. Harrower, confirming the moonlighting theory. I thought the illustrations looked pretty good, despite the printer having used a heavy-handed red in the page (nobody thought to send me the color proofs to check), and the layout was a welcome addition to my portfolio. Of course I’m no expert, but the text seemed somewhat trivial to me; and I keep recalling that poorly restrained, haughty sniff Dr. Harrower’s colleague had emitted at the mention of his name.

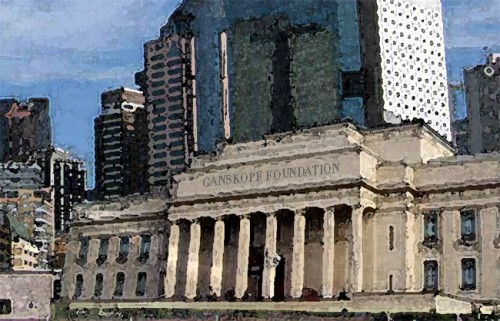

Strangely, not long after the incident I received a cold-call from someone named Rory Zohn at NEMECH, the New Elgin Museum of Cultural History, inviting me to interview for a full time position as Illustrator for the Unsecured Antiquities Collection. The interview got off to an odd start: Dr. Zohn’s first question wasn’t to see my portfolio or about previous job experience, but to ask me to recount the Ganskopf incident, even though he seemed to already know a lot about it. I didn’t leave anything out or spare anyone, including Dr. Danneru and his illicit mug of tea, and when I got to the comment about conservation departments, my interviewer just shook his head, muttering something that sounded like “supercilious bastard,” but clearly smiling behind his beard. I got the job, and I’ve been working there since, now fully acquainted with what “unsecured antiquities” are, and glad to not be surviving on freelance work alone. Stranger still, just last week while rummaging through a flat file at work, I found the archaic stone owls drawing. Rory said he’d had it for quite a while but had forgotten, and I was supposed to take it home. Somehow, distracted by his bad joke about the owls finally coming home to roost, I never heard how they had come to him.

but clearly smiling behind his beard. I got the job, and I’ve been working there since, now fully acquainted with what “unsecured antiquities” are, and glad to not be surviving on freelance work alone. Stranger still, just last week while rummaging through a flat file at work, I found the archaic stone owls drawing. Rory said he’d had it for quite a while but had forgotten, and I was supposed to take it home. Somehow, distracted by his bad joke about the owls finally coming home to roost, I never heard how they had come to him.

I’ve always wondered what happened to Miss Laguna – almost immediately after the incident, her name was gone from the staff roster on the Gankopf Foundation website. I couldn’t find out if the poor woman had been fired, or if she had quit. Perhaps she had fallen back  on her night job. I wondered if anyone – like for instance the person whose carelessness had lost her her career – had made any effort on her behalf. Considering his apparent lack of concern about the shattered “fetish”, it seemed unlikely. Yet, thinking of my own out-of-the-blue offer of a plum job at NEMECH, I had to admit it wasn’t impossible.

on her night job. I wondered if anyone – like for instance the person whose carelessness had lost her her career – had made any effort on her behalf. Considering his apparent lack of concern about the shattered “fetish”, it seemed unlikely. Yet, thinking of my own out-of-the-blue offer of a plum job at NEMECH, I had to admit it wasn’t impossible.

One thing I know with certainty: whoever replaced Miss Laguna as Ganskopf Librarian is bound to be a dragon for regulations concerning food and drink in the reading room. That was one damn costly mug of tea.

End

_________________________________________________________________

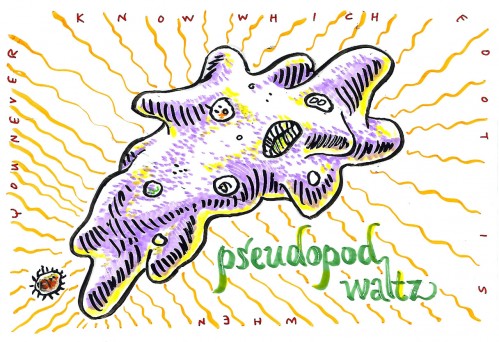

Coming soon, the next series, a prequel to the Ganskopf Incident: