The desert pops

Lots of rain, sunshine, and warm temperatures after a tough winter have started the desert’s flower-fueled engines, pumping poppies out of “nowhere” like magician ‘s flowers.

‘s flowers.

<< View across Bartlett Lake to SB Mountain in the Mazatzal Wilderness area. The bright orange wash just below the high peaks is poppy fields. The bright green on the lower right edge of the image is chartreuse lichen on the “Yellow Cliffs”.

E and I entered the flowery fray on Sunday, in search of blooms. The west side of Bartlett Lake was our destination — we realized we’d never been there in all these years — and it was good. To those searching solitude, I should explain that the lake itself is potentially off-putting; not its actual self, or setting, or vistas, which are spectacular, but because on weekends speed boats and jet skis and other motorized etceteræ mix with the sound of the breeze in the saguaro needles, and the blue calm of the water.

and other motorized etceteræ mix with the sound of the breeze in the saguaro needles, and the blue calm of the water.

>> Roadside mix of orange and less common white Mexican Gold Poppy (Eschsholzia californica ssp. mexicana, see last photo below for portrait of a white poppy)

This early in the season this traffic is bearable since it’s nowhere near the height of the boys-with-toys influx and fossil fuel frenzy which will invade after school’s out and with warmer temps. But here you’re on the edge of wilderness, not in it. Fortunately, the shoreside trail we chose to explore was near a non-motorized cove, which meant most of the motorcraft were inaudible on the opposite side of the lake, and the hardy, self-powered paddle-boarders and unexpected numbers of distance swimmers  braving the winter-cold riffles were impossible to object to.

braving the winter-cold riffles were impossible to object to.

<< More Mexican gold poppy and Coulter’s Lupine (Lupinus sparsiflorus).

The annual bloom seemed near peak, scattered in the granite gravelly bits among tough perennials like Chuparosa, Brittlebush, Pink Fairy Duster, Buckwheat, and Desert Lavender. The saguaros and other spring-blooming cactus haven’t begun yet here, but the Ocotillo are in leaf, and in a week or two their hot-poker flowers will ignite their branch tips.

New to us was the subtle but spectacular Mentzelia (probably involucrata, Sand Blazing Star), which we missed on the outward bound walk but caught on the back-track — probably because it opened its transluscent cream-colored flowers mid-morning, after we passed them earlier on. >>

cream-colored flowers mid-morning, after we passed them earlier on. >>

Lizards were the only reptiles we encountered — including the largest Tiger Whiptails I’ve ever seen! — and birds were active with spring pursuits. Most were “the usual suspects”: the locals like Northern Cardinals, Verdin, Rock and Cactus Wren, Common Ravens, an American Kestrel hunting for shoreline grasshoppers from a lake-side snag. There were some newly-returned breeders, like a Bell’s Vireo emitting its chewy song from within the brush, Black-tailed Gnatcatchers, Ash-throated Flycatcher, and a spectacular male Vermilion Flycatcher performing his rising, stalling, and calling nuptial flight, glowing red like a stoplight against the blue sky (click here to view an excellent slo-mo video of a male feeding). There was even a Turkey Vulture doing an impression of a shorebird (photo E.Shock)>>

(click here to view an excellent slo-mo video of a male feeding). There was even a Turkey Vulture doing an impression of a shorebird (photo E.Shock)>>

Chia buds were up and only beginning to open, but the curled necks of purplish Scorpion weed (Phacelia ambigua, below) nodded over the trail in places, as well as Woolly Daisies, two species of Camissonia, Whispering Bells, Fiddleneck, Blue dicks, Gilia, Cream cups, and Desert Marigold.

<< Scorpion weed (photo E.Shock)

About three roundtrip miles of hiking and a trip up the road yielded around twenty species of annuals either in bloom or about to bloom (no doubt more for those with more expertise).

For dessert, below is a close-up of a fully open, satiny white poppy, agitated by both bees and the breeze, dusted with its own pollen.

(All photos by A.Shock, unless noted. Be sure to click on each, in some cases to enlarge, but also because clicked-on images in WordPress generally have better resolution than images embedded in the text.)

Fiery forest revisited

Exactly one year ago this month, the White Mountains of eastern Arizona were ablaze with the Wallow Fire, the largest fire in state history. The human-caused fire scorched more than 530,000 acres in four counties in Arizona and one in New Mexico, significantly damaging or destroying hundreds of thousands of acres of wilderness habitat, as well as historic and residential buildings, water and timber resources, and range-land.

This weekend, E and I hiked and camped in the high-altitude mixed conifer-aspen, near-alpine grassland biome near Mt. Baldy, curious to see how the fire had affected some of the areas we know and love. In the few days we were there we found big changes, but perhaps not as drastic as we feared. We were able to camp and hike in favorite places, each scarred but not destroyed by the wildfire’s effects. The campground was only marginally burnt. I would love to know if this close call was a natural quirk of fire topography, or if firefighters saved the campground.

The campground was only marginally burnt. I would love to know if this close call was a natural quirk of fire topography, or if firefighters saved the campground.

<< aspen and ponderosa forest damaged by the 2011 Wallow Fire (Photoshopped edit, A.Shock photo)

Our relief that things weren’t worse than they were is the result of a non-technical, tourist viewpoint. For residents, both human and wildlife, the fire changed the landscape in ways that will not be restored in our lifetime. Blackened trees stand everywhere, some killed outright, others damaged and struggling. Fallen trees — some reduced to a trunk-sized trail of ash — criss-cross the forest floor. Some of the downed trees were felled as part of federal and state agencies’ safety strategies intended to make the most seriously burnt areas safer for hunters, hikers, and fishermen: many hazard trees near roads, structures, in campgrounds, and along trails have been cut down and piled into charred heaps by feller-buncher equipment and saw-crews. Bright yellow signs posted at every trailhead and forest road junction caution people venturing into the back country that flames are not the only dangers of fire: once the fires are out, flash flooding, falling trees and branches, and landslides are the legacy of wildfire for seasons to come.

But not all of the forest suffered equally: crown-fire areas, where the flames jumped from treetop to treetop, burnt hotter than others and show more severe damage. Ground-fire areas burnt  spottily, while other places were only lightly toasted. Some pockets were not touched by flames at all. Yet each of these places shows a welcome resurgence of life.

spottily, while other places were only lightly toasted. Some pockets were not touched by flames at all. Yet each of these places shows a welcome resurgence of life.

>> a foot-tall aspen regrowing in the shelter of a charred ponderosa trunk (Photoshopped edit, A.Shock photo)

Although Ponderosa pines appear to be hard hit in many places, aspen trees and firs growing alongside them often seem to have sustained less damage. In addition, 2012’s snowmelt and spring rains provided most areas with a green carpet of grass, re-sprouted shrubs, and young trees. Elk cows trail gangly calves, and busy Barn swallows, Hermit thrushes and Brewer’s blackbirds have bug-filled beaks, carrying food back to their nestling broods. A pair of Bald eagles has built a nest in the woods crowning a peninsula of a popular fishing lake: a joyful reason for an area closure, unlike the parts of the forest still closed to recreation because of severe fire damage.

unlike the parts of the forest still closed to recreation because of severe fire damage.

<< watercolor sketch of small aspen that survived the fire (A.Shock)

The flame-colored sky in the background of the top image is reminiscent of the fires that swept through the area last year. But it’s just a mid-June sunset glowing behind the aspens and Ponderosa pines where we camped. Ironically, the blazing sunset is caused by smoke particles in the air, wafting from wildfires currently burning in Arizona and New Mexico — the Poco fire near Young, AZ, and the enormous, lightning-caused Whitewater-Baldy Fire in New Mexico’s Gila National Forest , now classed as the largest fire in the history of that state.

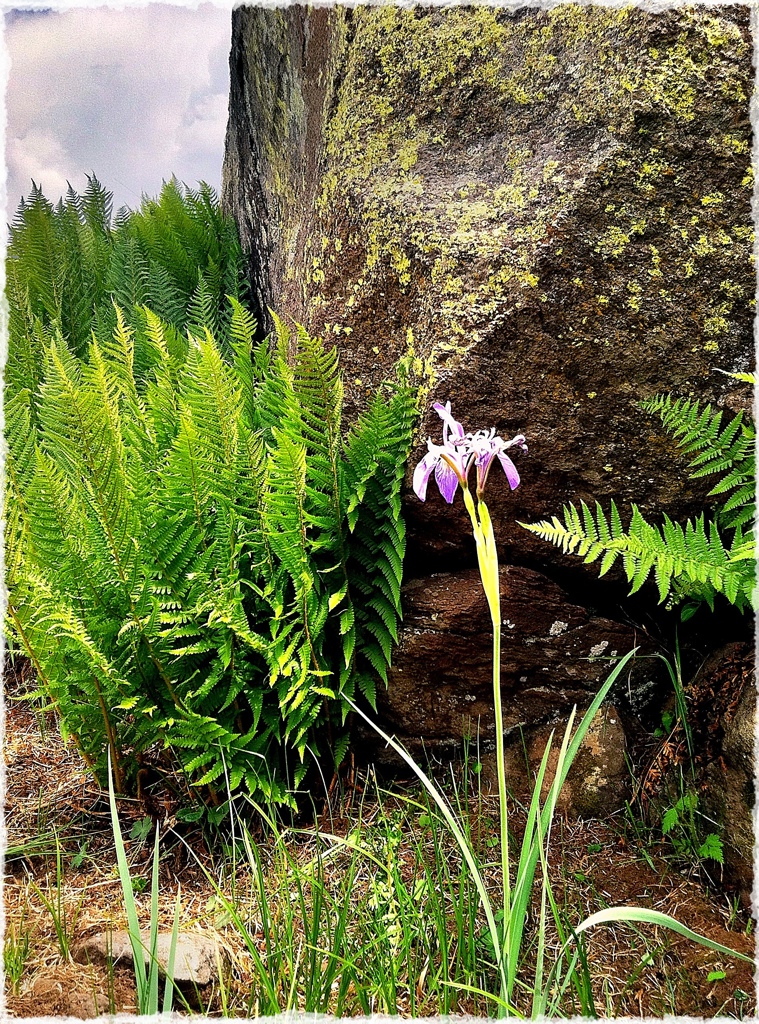

Secret rock

An outcrop in a high treeless field, slightly moister than the flat ground around it, sheltered ferns and flowers: golden columbine, and clusters of wild iris. The columbine was just starting, but the iris was spent, each stalk bearing a papery brown remainder of spring. All but this late blossom, which was still blue against the lichen spotted boulder. I’m glad we stopped — it would have been easy to just keep going. (photo A.Shock)

Up with the sunflowers

Low desert mornings are beautiful in May and June, the air still cool and crisp before the slight sogginess of monsoon season sets in later in the summer. The real desert is even cooler, but here in our corner of Phoenix there is enough open saguaro-y space in nearby Papago Park and few enough lawns in the ‘hood to maintain a deserty feel in the air.

space in nearby Papago Park and few enough lawns in the ‘hood to maintain a deserty feel in the air.

Sunrise this morning was prime, overseen by a waning gibbous moon still high in the sky, and I wandered into the back garden early to see who was around. I found a pair of complementary blooms: a passion flower winding up a sunflower — sunrise and moonset together on a garden scale.

While I was admiring them, tiny Lesser goldfinches flew into the sunflowers to fress. We put out nyjer thistle in feeders for them, but even still they’re always hungry enough to rifle the seedy charms of a sunflower. So we let the reseedlings take over the herb garden in the summer, and allow the basil plants and mexican hats go to seed for the little yellow dinosaurs, who repay us by spreading the seeds around for next year’s crop.

The Lesser Goldfinch below came within feet of me to feed. Her boldness can be interpreted as lack of experience — she’s a juvenile, and not as jaunty as the big boys, but she’ll do. (Photos A.Shock: upper, with iPhone4/Camera+app; lower, with Canon EOS xti, 55-250mm zoom)

A sketchy bird list

Not keen on enacting the Mad Dogs and Englishmen scenario, E and I lounged for a couple of hours during the heat of the day in the shade of a wild palm grove last weekend.

the heat of the day in the shade of a wild palm grove last weekend.

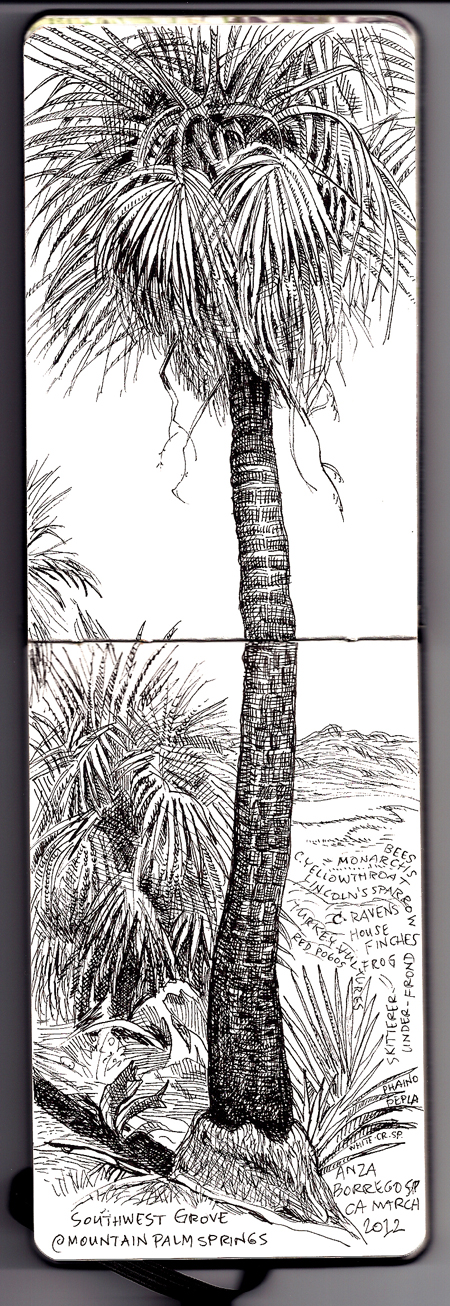

<< Southwest Palm Grove, Tierra Blanca Mountains, Anza-Borrego State Park (photo A.Shock)

This is a well-known oasis, and not terribly remote — but a destination doesn’t have to require too much hiking before you can expect to have the place primarily to yourself, especially if it’s slightly uphill. With only occasional others wandering through, we ate lunch and waited for the heat of the day to subside so we could march back across the desert to our campsite in the low sun.

wandering through, we ate lunch and waited for the heat of the day to subside so we could march back across the desert to our campsite in the low sun.

E doesn’t sit still very well, but he was amenable under the circumstances: just feet from the moist green calm of the grove, the white desert glared through dark trunks, reminding us of the hot, spiny, and hard path home. He read, and poked around the substantial grove with his camera. There was plenty to look at: like windmills, palm trees have a quality which readily vacillates between stateliness  and creepiness according to wind, light, and the observer’s mood. At noon on a calm day, these palms seemed merely sleepy and obliging, providing shade and coolth to travelers, both human and animal. I sat on a rock, choosing this outlier palm to scratch into a small Moleskine sketchbook with an excessively-finepointed pen, fussing over capturing the complicated but orderly rhythm of shadow and light on the pleated, fringed fans, and considering how to show the blackness of the trunk without losing the way the sun picked out its checkered texture. Slatted shadows wheeled around us as the sun rolled across the afternoon sky.

and creepiness according to wind, light, and the observer’s mood. At noon on a calm day, these palms seemed merely sleepy and obliging, providing shade and coolth to travelers, both human and animal. I sat on a rock, choosing this outlier palm to scratch into a small Moleskine sketchbook with an excessively-finepointed pen, fussing over capturing the complicated but orderly rhythm of shadow and light on the pleated, fringed fans, and considering how to show the blackness of the trunk without losing the way the sun picked out its checkered texture. Slatted shadows wheeled around us as the sun rolled across the afternoon sky.

Sitting still is a wonderful way to see birds, especially at a frondy desert oasis with high perches for cawwing ravens and low cover for furtive Lincoln’s sparrows and simultaneously sneaky and showy Common yellowthroats. Instead of keeping a list in a notebook, I wrote species’ names as they manifested in the palm’s portrait. It was possible to use a cramped scrap of background for this because bird diversity was low — the list was quite short, even with non-avian species like ants and butterflies included, and the few words provided the perfect coarse-textured, mid-range value for the desert beyond the grove.

<< Look closely, this isn’t just a landscape, or a portrait of a stately middle-aged California fan palm (Washingtonia filifera), it’s a bird list (click, twice, to enlarge).

Normally, previous years’ fronds cloak the trunks of Washingtonia palms to the ground, giving them a mammoth-legged look: sturdy, shaggy and brown. But this grove had burned sometime in the past few decades, leaving the surviving older palms bare-legged and carbony black, smooth and manicured like well-behaved resort palms. Little palms grew up around them, a decade or two old themselves, and bearing all their previous fans on their trunks naturally, indicating they’d sprouted after the last fire.

resort palms. Little palms grew up around them, a decade or two old themselves, and bearing all their previous fans on their trunks naturally, indicating they’d sprouted after the last fire.

>> glowing spines (photo E.Shock)

We timed the return trip well, and eventually hiked back to camp with the low sun behind us. It back-lit the cholla with a golden haze, and ignited the early Scott’s orioles perched on red ocotillo tips into melodious yellow flames. But the orioles wouldn’t hold still for a photo, and there was no time for a sketch; darkness falls abruptly in the desert.

The desert between

It exhibits questionable judgment to leave Phoenix right now when the Sonoran desert is so beautiful, but we did. In a fit of really-needing-to-get-out-of-town E and I enacted a spur of the moment plan for a busman’s holiday of camping in the Colorado desert*. We took off down I-8 in the footsteps of Juan Bautista deAnza himself, headed towards a bit of California desert between our desert in Phoenix and the desert under the currently snow-capped Peninsular peaks east of San Diego (see photo below, be sure to click to enlarge).

It exhibits questionable judgment to leave Phoenix right now when the Sonoran desert is so beautiful, but we did. In a fit of really-needing-to-get-out-of-town E and I enacted a spur of the moment plan for a busman’s holiday of camping in the Colorado desert*. We took off down I-8 in the footsteps of Juan Bautista deAnza himself, headed towards a bit of California desert between our desert in Phoenix and the desert under the currently snow-capped Peninsular peaks east of San Diego (see photo below, be sure to click to enlarge).

<< our tent above Bow Willow (all photos A.Shock unless noted)

Between. We arrived at the south end of Anza-Borrego State Park between weekends (it was spring break at ASU, so E was more or less at liberty mid-week). The weather was a slice of unseasonable summer between winter and spring, topped by a dry blue sky between pacific storms and a tarry, star-salted night sky between moons. It was a waiting wing of a moment, a pared-down parcel of between, when all that was in the desert was what was always there, the patient bare granite bones, the sun, cactus, creosote, and cool, rustling palms: the permanent residents. Ephemerals — the summer-breeding birds and annual wildflowers — hadn’t appeared in any numbers, yet.

bare granite bones, the sun, cactus, creosote, and cool, rustling palms: the permanent residents. Ephemerals — the summer-breeding birds and annual wildflowers — hadn’t appeared in any numbers, yet.

>> Overlooking the Carrizo Valley and the snow-dusted Tierra Blanca Mtns from the notch at the end of Smuggler’s Canyon

Arriving in any desert for peak wildflower bloom or migration at an oasis is serendipitous: we’ve managed it occasionally, sometimes by accident and sometimes on purpose — once for a songbird jam at Butterbredt Springs in the Mojave and twice for “jubilee” blooms in Death Valley only a few years apart. These were times we effortlessly tripped over the attractions and high points, unable to look away from showers of jewel-colored orioles and tanagers and thick carpets of bright petals. This between season was different: we had to look hard and close for things — the serendipity took more effort.

from showers of jewel-colored orioles and tanagers and thick carpets of bright petals. This between season was different: we had to look hard and close for things — the serendipity took more effort.

Ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens) being very splendid indeed; this one was about 10 feet tall >>

But the desert seldom disappoints and though between, this trip was no exception. The beavertail prickly pear, studded with fat pink-green buds, were clearly about to burst into glorious magenta bloom only after we were gone. But the tips of the Ocotillo were in flame, and in the few days we were there their thorny bleached stems scaled over with green leaves. Little fishhook cactus rocked coronas of creamy blossoms that looked glued onto their heads like fake straw flowers on a hat.  In places, a tide of tiny goldfields washed around the feet of gray wintery shrubs (see photo at bottom of post). The mesquite and desert willows were still bare, but the Elephant trees (Bursera microphylla) were green with their incense-scented leaflets, and deer vetch, creosote, and desert lavender were all blooming. Tangles of red-flowered chuparosa scrambled over granite boulders, and in tight crevices fronds of “resurrection plant” or desert mossfern (Selaginella sp) unfurled, instantly green and pliant after recent rains.

In places, a tide of tiny goldfields washed around the feet of gray wintery shrubs (see photo at bottom of post). The mesquite and desert willows were still bare, but the Elephant trees (Bursera microphylla) were green with their incense-scented leaflets, and deer vetch, creosote, and desert lavender were all blooming. Tangles of red-flowered chuparosa scrambled over granite boulders, and in tight crevices fronds of “resurrection plant” or desert mossfern (Selaginella sp) unfurled, instantly green and pliant after recent rains.

<< “Fishhook cactus” Mammillaria (probably) dioica. They need no more than a fracture in rock for a foot-hold, and seem to require no soil at all.

Birds were also in a between season: Rock wrens and Black-throated sparrows, present year-round on the rocky hillsides, were ubiquitous and vocal, along with Cactus and Canyon wrens, Costa’s hummers, quail, and ravens.  There were only occasional passers-through: a Lincoln’s sparrow in the palm oasis; surprising numbers of Sage thrashers moving through the Bow Willow wash. But the summer visitors were barely starting to trickle in — we found a couple of male Scott’s orioles alternately singing their ringing song and molesting nectar-oozing Ocotillo flowers, a Common Yellowthroat working the dense understory at the palm grove, and an Ash-throated flycatcher k-brkk‘ed near the campsite.

There were only occasional passers-through: a Lincoln’s sparrow in the palm oasis; surprising numbers of Sage thrashers moving through the Bow Willow wash. But the summer visitors were barely starting to trickle in — we found a couple of male Scott’s orioles alternately singing their ringing song and molesting nectar-oozing Ocotillo flowers, a Common Yellowthroat working the dense understory at the palm grove, and an Ash-throated flycatcher k-brkk‘ed near the campsite.

A Black-throated sparrow; who says sparrows are plain? (photo E.Shock) >>

Surprisingly, we were between when it came to snakes, too — we saw none, but I’m sure they were out. On the other hand, lizards were plentiful. Blue-bronze Granite Spiny lizards basked, and we were ignored hard by a harlequin Baja California Collared lizard sunning on a boulder right next to the trail.

<< Baja California Collared lizard (Crotaphytus vestigium) is a species of collared lizard found only in a small range in the US, as its name indicates.

The only disappointment of being between was that our transportation was between, too: we discovered after arriving that the truck’s four wheel drive wouldn’t lock in, leaving us with high-clearance passage but wimpy traction. This wasn’t an emergency but it ruled out more remote, difficult roads — we could only go where two-wheel drive or our two feet could take us, which turned out to be plenty for the short time we had. But we missed some interesting habitat like the Carrizo Marsh, and intriguing, fossiliferous geology that E is itching to check out.

We’ll have to get that 4-wheel drive fixed so that instead of between, next time we’ll definitely be smack-dab.

Low carpet of yellow wildflowers I know only as “Goldfields” >>

* The term “Colorado Desert” generally refers to the portion of the Sonoran Desert that lies within the state of California.

What luck!

This morning, I found a golden egg, high up in a tree.

This morning, I found a golden egg, high up in a tree.

Nestled into the rough bark of our backyard mesquite, a magical bird had laid a golden egg. This was excellent: what a windfall! — my fortune was secured, if only I could reach it.

But it was too far over my head, so I had to satisfy myself with longing for its golden curves through binoculars.

And guess what, it wasn’t an egg at all, but some type of -quat or other: kum-, or perhaps lo-. Yes, that was what it was: a small orange fruit, probably a loquat since a neighbor has a tree, wedged into somewhere safe by a bird, or maybe a squirrel, to be retrieved later.

Who would do such a thing, hiding a golden treasure in plain sight? The jammer would have to have sufficient strength, beak/jaw gape, toe-grasp, cleverness and agility to handle hauling a small fruit into a tree, and stashing it on a vertical trunk. There are several candidates, but I strongly suspect the Curve-billed thrashers, who have just fledged their ravenous brood and are working incessantly, combing every crevice in the yard to feed their greedy-gaped offspring. These industrious foragers will eat anything, seed, suet, bug, or fruit. And they have an eye for treasure, just as golden as loquats.

but I strongly suspect the Curve-billed thrashers, who have just fledged their ravenous brood and are working incessantly, combing every crevice in the yard to feed their greedy-gaped offspring. These industrious foragers will eat anything, seed, suet, bug, or fruit. And they have an eye for treasure, just as golden as loquats.

(All images A.Shock).

Boojum moon

“In the dark was a boojum, you see,” to paraphrase Lewis Carroll.

“In the dark was a boojum, you see,” to paraphrase Lewis Carroll.

The javelinas, bats, and skunks get to see it like this all the time. But before last friday night, I’d never seen a boojum in the moonlight.

Turns out waxing gibbous is a good look for the strange tree.

(Boojum, Fouquieria columnaris, or cirio in Spanish, “candle”. Photo A.Shock, Boyce Thompson Arboretum)