Good owls come in strange places

When I tell my non-birding friends that we saw quite a few owls in Costa Rica, many of them are surprised. The common perception is that owls are indeed woodland creatures, but that’s “normal” woods — not, you know, the “jungle.” I suspect this monolithic concept of owls — where “owl” pretty much equals “great horned owl” — arises in part from our being exposed from early on to things like halloween images of owls perched in leafless trees over tombstones, defining owls glibly as creatures not only of the night, but of deciduous woodland. For many, it even takes some getting used to think of owls as desert creatures, living in and on saguaros, and eating scorpions and other Sonoran fare.

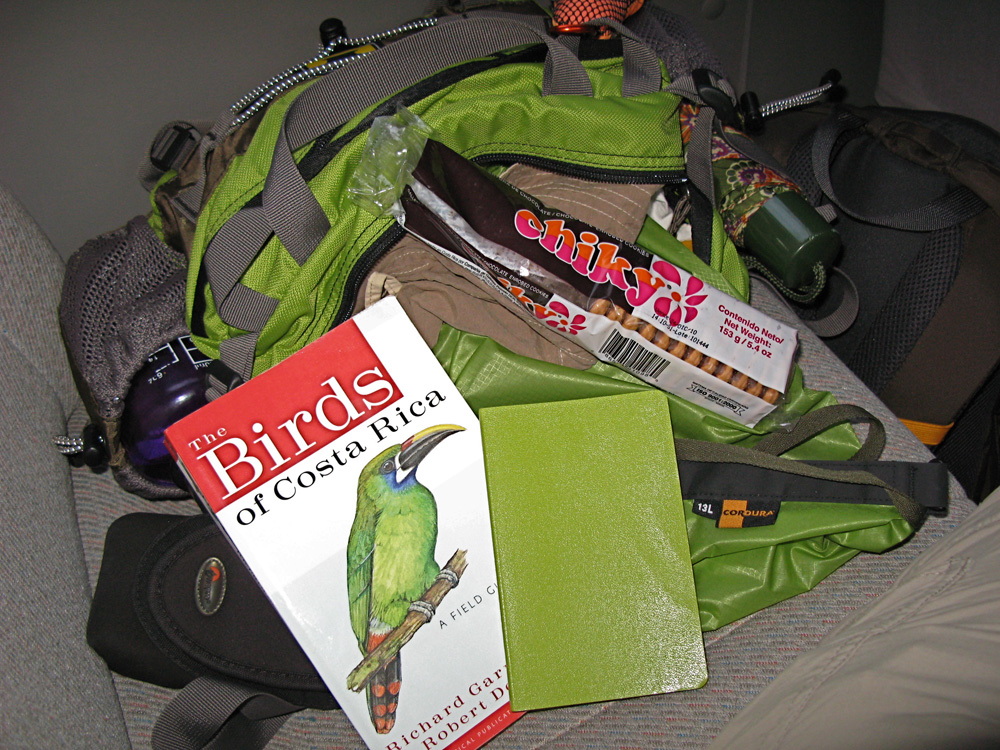

So the concept of tropical owls takes many people by surprise. Of course, owls are at home in rain forests as much as woodlands and wetlands and tundra. Just not the same owls in all of those places, for the most part. There are in fact  many species of tropical owls in central America, some endemic to Costa Rica, others widespread in tropical habitats from Mexico to South America.

many species of tropical owls in central America, some endemic to Costa Rica, others widespread in tropical habitats from Mexico to South America.

One of the latter is the aptly named Black and white owl (Ciccaba nigrolineata). They are birds of moist forests. They also can be found in urban and suburban habitats within that range, much the way Great horned owls successfully exist in proximity to human settlements.

<< Black and white owl scratching its itchy face (digiscoped by C.Gómez)

This Black-and-white owl was roosting in the central city park in the town of Orotina CR, high in a tree it was sharing with a sloth, spending the middle of the day preening itself and scratching its face with its strong-toed yellow foot. It could only be seen by standing directly below its branch and looking straight upward.

From an owl’s viewpoint, a city park is a good place to hunt large insects, like cockroaches, and small mammals, like mice and bats. From a human point of view, it was humorous to be enjoying such an excellent owl in such an urban setting: we were surrounded by ice-cream vendors, mothers strolling their babies, pan-handlers, too-cool teenagers eyeing each other, and romping, boisterous children, as we craned upward in broad daylight at an owl who seemed to care nothing for all the traffic noise and people far below it. The owl’s primary concern seemed to be that its face itched. As it scratched like a cat, rapidly kicking at its facial disc with a talon or two, bits of down fluff, owl dander, and even a contour feather drifted down unnoticed onto the activity and bustle in the park below.