Passing on the shnorr-gene

Hoover, the semi-tame African Collared Dove who hangs out in our neighborhood, has been a bachelor for a while. But earlier this summer, we observed him in the company of a female dove who appeared to be a smallish Eurasian Collared Dove, a naturalized old world species that has become very numerous across the US. African Collared Doves are also non-native but less common; our Phoenix-area neighborhood just happens to sustain a small population probably descended from birds released in nearby Papago Park a couple decades ago.

We wondered if these two had something going on. We may have had our answer this morning, when Hoover showed up for his daily handout with Offspring. Darker than its parent, the young one was just starting to develop the black neck-ring that both of its parents have. The little dove didn’t fall very far from the branch; after some jostling, both birds settled in for a feed on E‘s outstretched hand.

The young one has the typical gangly, big-beaked look of an immature dove. (Photo A.Shock)

By the way, I don’t recommend hand-feeding wild birds. Hoover was initially hand-tamed by soft-hearted neighbors. We inherited the “responsibility” sort of accidentally, while caring for our neighbor’s yard a while ago, and have continued it out of the same soft-hearted impulse. Now the behavior seems to be being passed on to the next generation. Time will tell if the youngster will learn Hoover’s in-your-face-wheedling technique of zooming low over our heads whenever we’re outside and he’s in the mood for safflower seeds.

By the way, I don’t recommend hand-feeding wild birds. Hoover was initially hand-tamed by soft-hearted neighbors. We inherited the “responsibility” sort of accidentally, while caring for our neighbor’s yard a while ago, and have continued it out of the same soft-hearted impulse. Now the behavior seems to be being passed on to the next generation. Time will tell if the youngster will learn Hoover’s in-your-face-wheedling technique of zooming low over our heads whenever we’re outside and he’s in the mood for safflower seeds.

The night of the enormous centipede

Last big monsoon event brought rain and a spadefoot to our Phoenix area yard. Tuesday night’s big monsoon event brought even more rain and a centipede.

Last big monsoon event brought rain and a spadefoot to our Phoenix area yard. Tuesday night’s big monsoon event brought even more rain and a centipede.

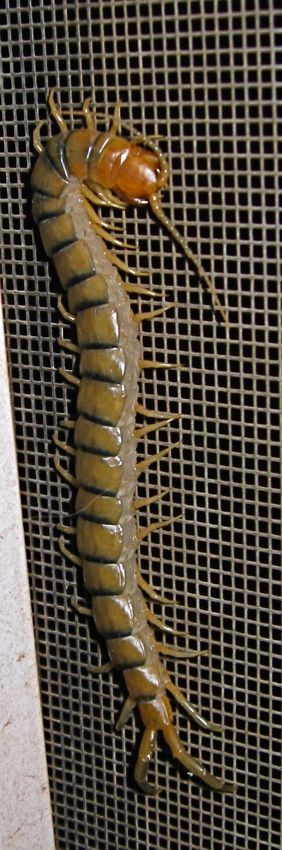

This guy is a Scolopendra polymorphus, a Sonoran centipede, sometimes called a tiger centipede. This one is about 4 inches long (they can grow up to about 7 inches), and has crawled up the outside of our back door screen, possibly in search of prey, or maybe to escape flooding in the nearby soil, where it very likely dens up.

It’s a beautiful animal, although I have to admit I’m not partial to centi- or milli-pedes (it may be all the pointy little appendages) but as this one’s a neighbor, I’m trying to be inclusive. Apparently, I’m not the only one who has a hard time liking them. Our cat, Hector Halfsquid, spent the evening on the inside of the wet screendoor alternately approaching hesitantly and hurriedly backing away from the centipede, giving the impression of being simultaneously fascinated and repulsed by it.

(Photos A.Shock)

In fact, even today he’s still giving occasional neurotic “creepy hops” where from deep sleep he suddenly jumps out of his skin, apparently having received Gary-Larson-esque “cumulative willies” from the many-legged visitor. Hector’s wariness is probably justified, as these guys can deliver a powerful and venomous bite; not dangerous in most cases, but certainly painful.

Further fun with spadefoot

Saturday night in our yard, a Couch’s spadefoot emerged after a substantial monsoon event, and used our swimming pool as his stage to advertise his availability to females, and sovereignty to other male spadefoots. (See previous post.)

sovereignty to other male spadefoots. (See previous post.)

<< Spadefoot in the pool net, after exciting dawnzerlylight rescue orchestrated with dramatic Great horned owl background music (photo A.Shock). Look at those eyes — better than dichroic glass!

Swimming pools are not terribly good for wildlife. Wonky chemistry + steep sides = unfriendly locale. At two in the morning, however, I was not able to fish out the wary spadefoot, who fled to the bottom every time I approached with the soft mesh pool skimmer to rescue him. Eventually he swam right to the very deepest depths of the deep end, where even the long-handled skimmer pole could not not reach.

So, I assembled an impromptu spadefoot ramp. Mr. Spadefootdude had been calling consistently from one spot at the edge tiles of the shallow end, so rustling up a four-foot one-by-ten and some bricks, I put the structure there in the hopes he’d return to his  stage after I’d gone away, and climb out if he wished.

stage after I’d gone away, and climb out if he wished.

<< Spadefoot ramp. Like purpose-made cat toy, not used by spadefoot.

Sunday morning, I got up at dawn to check on his progress. After the rain it was cool enough to shut down the AC and open doors and windows, so the Great horned owls duetting from the alley phone pole had awakened me anyway. These were very late hours for them, as the sky was lightening, and the Brown crested flycatchers and Abert’s towhees were already up, brrting and chnking. Sure enough, the spadefoot was still in the pool, strongly kicking along the bottom of the deepest part with its sturdy legs.

By now I was more awake (and more coordinated), so using both the pool brush and the skimmer, I managed to gather the spadefoot gently in the net and lift him up to the surface. He paused for the photo portrait above, then competently took himself off hopping, to find a sheltered hiding spot for the day.

If you are wondering why the word “toad” doesn’t appear in these spadefoot posts, it’s because, toadly as they look, spadefoots are not true toads. On the

basis of structural differences, they have been assigned their own family, Pelobatidae, which means spadefoot in Greek. More info here.

Coincidentally during that very spadefoot night I’d done a smoke firing, and in the bin were two batrachian images, frogs to be sure (prominent tympanum instead of parotoid gland), but still in the ballpark.

<< Here’s one of the whistles, very Couchy. They’ll be offered at Southwest Wings Birding and Nature Festival in Sierra Vista next week (object and photo A.Shock).

I hope the spadefoot doesn’t make a return appearance on his watery stage tonight; I might not hear him again, if the windows are closed. I guess that toadramp will be staying in place a little longer. “wraaaaaaah”

Good owls come in strange places

When I tell my non-birding friends that we saw quite a few owls in Costa Rica, many of them are surprised. The common perception is that owls are indeed woodland creatures, but that’s “normal” woods — not, you know, the “jungle.” I suspect this monolithic concept of owls — where “owl” pretty much equals “great horned owl” — arises in part from our being exposed from early on to things like halloween images of owls perched in leafless trees over tombstones, defining owls glibly as creatures not only of the night, but of deciduous woodland. For many, it even takes some getting used to think of owls as desert creatures, living in and on saguaros, and eating scorpions and other Sonoran fare.

So the concept of tropical owls takes many people by surprise. Of course, owls are at home in rain forests as much as woodlands and wetlands and tundra. Just not the same owls in all of those places, for the most part. There are in fact  many species of tropical owls in central America, some endemic to Costa Rica, others widespread in tropical habitats from Mexico to South America.

many species of tropical owls in central America, some endemic to Costa Rica, others widespread in tropical habitats from Mexico to South America.

One of the latter is the aptly named Black and white owl (Ciccaba nigrolineata). They are birds of moist forests. They also can be found in urban and suburban habitats within that range, much the way Great horned owls successfully exist in proximity to human settlements.

<< Black and white owl scratching its itchy face (digiscoped by C.Gómez)

This Black-and-white owl was roosting in the central city park in the town of Orotina CR, high in a tree it was sharing with a sloth, spending the middle of the day preening itself and scratching its face with its strong-toed yellow foot. It could only be seen by standing directly below its branch and looking straight upward.

From an owl’s viewpoint, a city park is a good place to hunt large insects, like cockroaches, and small mammals, like mice and bats. From a human point of view, it was humorous to be enjoying such an excellent owl in such an urban setting: we were surrounded by ice-cream vendors, mothers strolling their babies, pan-handlers, too-cool teenagers eyeing each other, and romping, boisterous children, as we craned upward in broad daylight at an owl who seemed to care nothing for all the traffic noise and people far below it. The owl’s primary concern seemed to be that its face itched. As it scratched like a cat, rapidly kicking at its facial disc with a talon or two, bits of down fluff, owl dander, and even a contour feather drifted down unnoticed onto the activity and bustle in the park below.

in which I reveal my graphic petticoats along with an Orange-billed sparrow

… or, saving shots by going artsy…

Not all photos are created equal, especially if you’re an amateur photog like me who asks my competent but limited point-and-shoot digital camera to do things it wasn’t meant to do, like capture images of cryptic birds high in trees with too many leaves against the light on an overcast day through a fogged-up scope (see previous potoo posts) in a hurry.

And, some birds don’t have the courtesy to pose standing still six feet away in the open in the light for an hour while some fudge-fingered camera-camel like me tries to get a shot  off before they get on with their lives finding scarce food, competing for mates, and evading swift-grasping predators.

off before they get on with their lives finding scarce food, competing for mates, and evading swift-grasping predators.

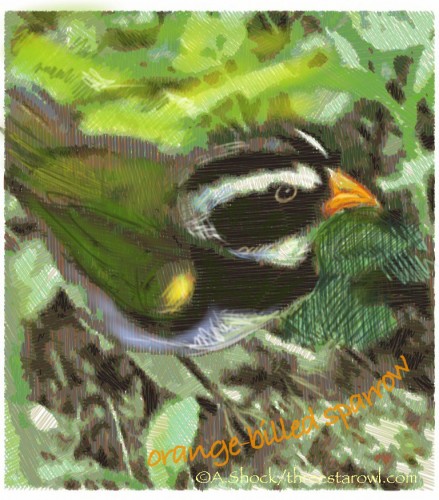

<< app-altered digital image of an Orange-billed sparrow (photo and alteration A.Shock). Orange-billed sparrows (Arremon aurantiirostris) are striking but rather skulking sparrows inhabiting moist woodlands from southern Mexico to northern South America, not terribly uncommon or hard to see but tough to photo. A bold black-and-white head pattern, a lovely olive back, golden epaulette and neon orange bill make them distinctive as they hop about the shadowy forest floor in small flocks.

So, not all photos are created equal. I have lots of “unequal” photos from trips, including this last Costa Rica visit. Despite expert bird-finding leadership turning up an unexpected number of fabulous sightings by eye, dim and moisty cloud forests, furtive species (and you know who you are, Silvery-fronted tapaculo), and awkwardly-wielded umbrellas all cut down the number of useful pix to post here. Some species (Quetzales for instance) I missed entirely; others, such as the Orange-billed sparrow, I only got blurry, distant, or otherwise unusable images of. Photoshop (even the archaic version I’m still using) and iPhoto are both hugely helpful, and have saved many a photo for publication. But now I have new tools — cribs, if you insist — to produce internet-ready images for this space from unpromising jpegs. (Let me add FYI, in case the reader hasn’t read the fine print at threestarowl.com, that this is not a commercial blog, and I receive no compensation whatever for testing, using, praising, demonstrating, criticizing, or even just mentioning any product, service, or company).

A recent fairly unintentional acquisition of an iPad has given me tools that are similar to Adobe Illustrator and its kin, but are even more user-friendly: SketchmeeHD, SketchbookPro, and TypeDrawing. Here is the step-by-step process by which I used these apps to turn an unusable jpeg image into a lively illustration for this post:

<< Far left, original unaltered shot of Orange-billed sparrow: subject too small to see. Near left, cropped to zoom, the colorful plumage and bill are captured, but the lack of focus due to movement and low light is painfully evident. Verdict: not publishable in either form.

So, I sicced the iPad app “SketchmeeHD” on the cropped version of the original jpeg. This cool application renders an original image into an algorhythmically-generated series of layered colors and strokes, as if it were drawn from colored pencil. It’s easy and quick for the operator (and entertaining, as the image is produced in stages as if being drawn before your eyes by an invisible hand), and nearly but not entirely id iot-proof: there are choices to make, such as opacity, density and substrait.

iot-proof: there are choices to make, such as opacity, density and substrait.

<< These were the results. It looks adequate artistically (click to enlarge to see pencil-marks), but it’s a bit mechanical looking, sterile. Annoyingly, but not surprisingly, the lack of focus was faithfully transmitted from the source image, and not magically cured. Worse, from a birder’s point of view — and probably a bird’s, too — all the distinctive colors have been muted to the point of dullness. Where’s the olive back? The golden epaulette? The eye? The eponymous orange bill, for crying out loud? These are Important Characteristics, Field Marks, and not to be done without, even if this is not a field guide. Especially if they’re only eradicated by the mere randomness of digital manipulation. Verdict: insufficient improvement, unpublishable.

But, I have recourse. At this point, I opened the SketchmeeHD-altered jpeg with SketchbookPro, another iPad app. By “drawing” with my finger on the iPad’s interactive screen and selecting parameters such as color, point type, width and opacity, I was able to  restore liveliness and color to the automatically-generated “pencil strokes” by adding my own hand-controlled digital marks which, even through the electronic medium, supply the human touch, visible in the finished version.

restore liveliness and color to the automatically-generated “pencil strokes” by adding my own hand-controlled digital marks which, even through the electronic medium, supply the human touch, visible in the finished version.

<< The final step was to use the app TypeDrawing to add the bird name caption. This app allows you to enter type in a color, size, font of choice and place it in your image; the path of your finger on the screen determines the line and position of the text.

Verdict: Publishable illustration of Orange-billed sparrow.

The photos I use on this site, whether taken by me or others, are minimally altered for clear viewing, and never “faked” (except for fictional effect and with full disclosure). Altering photos to prove the identification or occurrence of a bird in a particular place or time is obviously just wrong (for instance, my Maroon-chested dove shots are unaltered except for cropping to enlarge the bird, and the video is entirely unaltered). Images in this blog, for the most part, are intended to tell a story, please the reader (and myself), and provide visual  interest besides text. Most are digital photos. Some, like the joyfully garish Resplendent Quetzal image are produced entirely from scratch from a blank “page” with SketchbookPro, driven by the touch-interaction of the iPad screen with my nail-bitten finger.

interest besides text. Most are digital photos. Some, like the joyfully garish Resplendent Quetzal image are produced entirely from scratch from a blank “page” with SketchbookPro, driven by the touch-interaction of the iPad screen with my nail-bitten finger.

By contrast, an image like the Orange-billed sparrow above is heavily altered — in fact, it’s published only because of my ability to alter it. I do “real drawings” too with pencil, colored pencil, and water color, and to me the apps are not going to replace those techniques — they’re just a different medium than those more traditional paper-born tools, with different limitations and different advantages. Maybe you’re comfortable with this process, maybe not. Possibly, by posting the techniques behind the results, I’ve made readers think less of a finished product like the Orange-billed sparrow image, as not being real “art”, or requiring less skill than a “real drawing”. That’s up to everyone to decide for themselves. Personally, I consider it illustration, and I’m thrilled to be able to present a pleasing visual image of a lovely creature that otherwise would have remained uselessly stuck in the craw of my computer.

Break from the tropics

Yes, you guessed it, this is not a photo from the recent Costa Rica trip. I thought a frosty retreat from the steamy tropics was in order, and decided to insert this flashback of a favorite photo and sighting from  a 2004 trip to the Antarctica Peninsula: a Gentoo penguin parent about to feed its chick. This is the bill-tapping action that encourages each bird to open wide to complete the transfer of semi-digested krill from the adult to the chick.

a 2004 trip to the Antarctica Peninsula: a Gentoo penguin parent about to feed its chick. This is the bill-tapping action that encourages each bird to open wide to complete the transfer of semi-digested krill from the adult to the chick.

Enjoy!

(I didn’t have a weblog back then, so periodically I post flashbacks from this trip and a later Galápagos adventure, which were both fabulous voyages with family.)

Hordes of hummers

Living in Arizona there’s no room for complaint about the quantity and loveliness of the hummers which visit our yard feeders. In the Phoenix area we have Costa’s and Anna’s year round, Black-chinned in summer, with Broad-tailed and Rufous making migratory appearances. I’ve seen a brilliant Broad-billed just two miles from here at the Desert Botanical Garden, so it’s a potential yard bird, as well. Further southeast in the state, hummer numbers swell to around 17 species — by contrast much of the U.S. hosts only one species, the Ruby-throated.

So only a truly spectacular hummer turn-out would impress a southwestern observer. Without doubt, Costa Rica provided that. During a thirteen-day trip, in various habitats and elevations, we saw about 34 species of hummers. Most I couldn’t capture in pixels: with a zoom-impaired camera, the best chance I have for snagging hummingbirds in photos is at feeders. These three posed obligingly on and around the feeders of Savegre Mountain Lodge.

<< Green violet-ear (Colibri thalassinus). These were quite common, and quite beguiling. A bit crabby, too: when another hummer got too near, those violet-ear patches would flare outward. Very threatening; we quailed at the sight. This bird has new feathers molting in on its forehead, visible as tiny white quills, still wrapped in  whitish keratin like shoe-lace ends to facilitate outward growth.

whitish keratin like shoe-lace ends to facilitate outward growth.

>> Right: male Volcano hummingbird (Selasphorus flammula). These little toughies are related to our norte americaño Selasphori like Allen’s, Rufous, and Broad-tailed, and are just as glittery green-gold-bronze. This Cordillera de Talamanca subspecies has a plummy sheen in its gorget, slightly visible in this photo.

And lastly, below is a female White-throated mountain gem (Lampornis castaneoventris) feeding at an aloe, or perhaps a Kniphofia, flower. Her mate (not shown) has a spotless white throat and an azure forehead, but the female is marked with a handsome rusty underside, the “chestnut-belly” of its species name, castaneoventris.

has a spotless white throat and an azure forehead, but the female is marked with a handsome rusty underside, the “chestnut-belly” of its species name, castaneoventris.

(All photos A.Shock)

The Boss in her office: “checking for lard”

[This is a Spot the Bird, although it’s less of a quiz than a photo series. All photos A or E Shock. Click to enlarge.]

Here are some feral date palms, growing wild at a substantial oasis in Death Valley, CA. The date palm is Phoenix dactylifera (“finger-bearing”), but in this case we could call it P. bubifera, “owl-bearing.” There’s an owl in this palm, although you can’t see it. >>

Here are some feral date palms, growing wild at a substantial oasis in Death Valley, CA. The date palm is Phoenix dactylifera (“finger-bearing”), but in this case we could call it P. bubifera, “owl-bearing.” There’s an owl in this palm, although you can’t see it. >>

Owls seem to like roosting in palms. Every birder the world over checks palms for owls. Great horned, Barn, Grass, whatever the local species are — if there are owls and palms together in a habitat or region, they are likely to be acquainted. This is because palms (like pine trees) provide what owls like: concealing, sturdy roosts, and habitat and food source for prey items. An owl perched hidden in palm fronds has a grand view of scurrying, foraging rodents at its feet — imagine regularly finding dinner on your very own kitchen floor… or, to quote Homer: “Mmmm, Floor Pie!” (that’s the epic Homer Simpson, not Homer the epic poet).

dinner on your very own kitchen floor… or, to quote Homer: “Mmmm, Floor Pie!” (that’s the epic Homer Simpson, not Homer the epic poet).

Spot the bird: In the center of this photo, you can see a vague milky blur on the right edge of the darkest dark: the vermiculation, or fine breast barring, of a Great horned owl, Bubo virginianus. >>

It’s nearly invisible because its distinctive yellow eyes aren’t visible; owls roosting in plain sight will often consider themselves concealed by squinting. When even one eye is revealed, the bird  become easier to spot. <<

become easier to spot. <<

I’ve checked a lot of palm trees. I never find owls in them (although I know others who have), but I keep checking. This repeated optimistic searching is known in our family as checking for lard. The term was coined after a cat named the Beefweasel found an unattended pile of chopped fat on a windowsill in our St. Louis apartment, waiting to be put outside for winter-hungry titmice and chickadees. Making good her name, the Beefweasel wolfed down the yummy chunks. Balancing on her hind legs and sniffing hard, she checked that bountiful window-ledge for years hoping for a fatty repeat. Birders are well-known to check for lard, too: there was a nut tree in St. Louis that was searched every winter by local birders on field trips because once in a decade past it had hosted an out-of-range Bohemian waxwing. Among birders, places to check for lard are passed down as oral tradition: I knew about that pecan tree, but the waxwing that made it famous alit there long before my time.

So out of habit  and hope, I was checking these particular palms with my binoculars, searching the deepest shadows for Good Feathery Detail (vermiculation). And there was an owl.

and hope, I was checking these particular palms with my binoculars, searching the deepest shadows for Good Feathery Detail (vermiculation). And there was an owl.

>> The bird never fully unhid; this was the maximum best sighting it allowed.

It was a Great horned owl, tucked in out of the breeze, and not at all worried about us (although we didn’t go very close, being equipped with telephoto lenses and optics — owls are like cats; sometimes you have to respect their invisibility, even if it’s just in their heads).

It’s so delightful to luck into a surprise owl (which, mostly, they are), that we talked about it for the rest of the trip. We referred to this bird as “the Boss in her Office”, because she reminded me of a boss I once had, who lurked invisible at her desk most of the time. Although she was hidden from us as we scurried around busily, it was never a good idea to forget she was there…

It’s so delightful to luck into a surprise owl (which, mostly, they are), that we talked about it for the rest of the trip. We referred to this bird as “the Boss in her Office”, because she reminded me of a boss I once had, who lurked invisible at her desk most of the time. Although she was hidden from us as we scurried around busily, it was never a good idea to forget she was there…