A vulture blew up in a bisque kiln yesterday. Dang! And it was my own fault, too, a foolish, neophyte error: its body was hollow, and I forgot to make a hole in it for the hot air inside to escape, kerPOW. The carnage is visible, right. Fortunately, nothing else in the kiln was harmed.

A vulture blew up in a bisque kiln yesterday. Dang! And it was my own fault, too, a foolish, neophyte error: its body was hollow, and I forgot to make a hole in it for the hot air inside to escape, kerPOW. The carnage is visible, right. Fortunately, nothing else in the kiln was harmed.

Vultures have been on my mind recently. Not only because I’ve been making turkey vulture items like the candle-holder that blew up, and the small “bottle” with the movable head in a recent post, but because of a show I watched recently on PBS.

It wasn’t about vultures. It was called the Dragon Chronicles, and it was an episode of Nature with a genial herpetologist traveling around the other hemisphere finding examples of real reptilian organisms which shared some of the characteristics of dragons, to promote how each could have given rise to the existence of the legendary fire-breather. It was a pleasant way of spending a TV hour, but the basic premise seemed a bit of a stretch because the narrator put forth several separate organisms rather than one as possible sources of the dragon legend.

I’ve got a different theory. I think tales of dragons arose from encounters with vultures. Think about these “known” characteristics of Dragons: they are reptilian and large, with snaky necks, they fly, live in caves, horde treasures, are long-lived, wise, fire-breathing, and man-eating. You can make a good case for each of these also being true of vultures:

Eurasian black vulture. Photographed by Julius Rückert.

Vultures are very large; in the Old World, the Eurasian black vulture of mountainous regions between the Iberian peninsula and Korea is one of the largest birds of prey in the world, massive by both bulk and wingspan (weighing in at nearly 30 lbs and keeping this heft in the air with a nearly 10 foot wingspan). Its nearest competitors, the Lappet-faced vulture and Andean Condor, are also airborn giants. With their bare neck and head, vultures are quite reptilian but, unlike modern reptiles, they can fly. Their contour plumage is stiff and when a vulture rouses (shakes) to adjust disarrayed feathers it rattles like a scale-covered creature, often emitting scraps of fluff and powdery cuticle flakes from feather sheaths. They lay eggs which are much larger than most birds’, and if broken, would have a baby vulture embryo inside, looking very dragon-like. Many species of vulture roost and nest in caves and ledges, often in inaccessible peaks and cliffs, where their (to our noses) malodorous lairs are filled with a loose pile of sticks, droppings, and debris — maybe not golden treasure, but a heap of stuff for sure. In the case of the European vulture-like raptor the marrow-eating Lammergeier (photo below), there are often bones on the ledge, enhancing its image as horder. When approached too closely, a vulture will hiss loudly, and when pressed further, will sometimes disgorge the contents of its stomach in a forceful jet — like breathing fire. This disagreeable material (remember they are carrion eaters) is acid enough to be corrosive.  A fine deterrent to an interloper, this is also a way of lightening the load for flight. Most vultures are long-lived, and there are records of Turkey Vultures living past 60 years in captivity. They are “smart” in the way people mean it, because to some degree all vultures are social, interacting in large numbers at carrion and in migration. As for man-eating? Well, long bones in the lair could be interpreted as human by someone who only got a quick glimpse before being driven away by an enraged incubating vulture’s hot projectile carrion slush. Grimmer still, in times when battlefields and other human casualties were not always swiftly cleaned up, vultures would have made meals of human dead. As nature’s “Nettoyeurs” (remember Jean Reno in La Femme Nikita?) it isn’t uncommon even today for vultures to be blamed for deaths of livestock they didn’t cause, but were taking advantage of.

A fine deterrent to an interloper, this is also a way of lightening the load for flight. Most vultures are long-lived, and there are records of Turkey Vultures living past 60 years in captivity. They are “smart” in the way people mean it, because to some degree all vultures are social, interacting in large numbers at carrion and in migration. As for man-eating? Well, long bones in the lair could be interpreted as human by someone who only got a quick glimpse before being driven away by an enraged incubating vulture’s hot projectile carrion slush. Grimmer still, in times when battlefields and other human casualties were not always swiftly cleaned up, vultures would have made meals of human dead. As nature’s “Nettoyeurs” (remember Jean Reno in La Femme Nikita?) it isn’t uncommon even today for vultures to be blamed for deaths of livestock they didn’t cause, but were taking advantage of.

Lammergeier, photo by Richard Bartz.

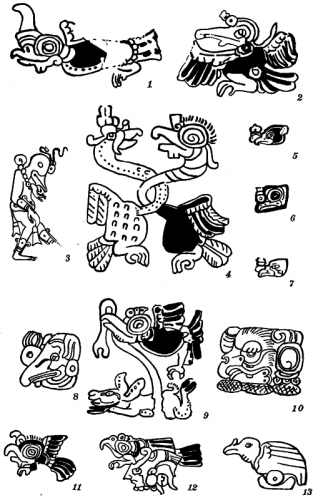

I should add that there are also dragon-type creatures in the mythology of the New World, like the cliff-dwelling, human-devouring Piasa Bird of the Mississippi valley, and of course, Black Vultures and Turkey vultures live in the U.S., not to mention California Condors which had a range of nearly the entire U.S. in the times legend would have been made. And this doesn’t even scratch the surface of New World vulture mythology; the King Vulture of Central and South America has a prominent place in the mythology of the Maya.

There’s no way to know for certain that vultures were the source of the dragon myth, but I find vultures to be the closest thing to dragons that I’ve personally experienced.

Right now most Vultures that breed in the U.S. are on their wintering grounds, in the far southern states and points farther south. Even in toasty Phoenix, we won’t see them again regularly until spring, where as in so many places like Hinckley Ohio their return is celebrated on a specific date. Here in central Arizona, it will be around the third week of March. So after that, look up in the sky and see if you can Spot the Dragon.

To the right are Turkey Vulture Candle-holders from Three Star Owl (inquire for pricing).

Bonus fact about turkey vultures: they have an excellent sense of smell, and I’ve heard that some Gas companies use a rotty-smelling compound called ethyl-mercaptan in their gas, to check for open-country gas leaks by looking for kettles of (frustrated!) vultures circling over broken pipeline.

Bonus bonus trivia about Lammergeier, from Wikipedia:

The Greek playwright Aeschylus was said to have been killed in 456 or 455 BC by a tortoise dropped by an eagle who mistook his bald head for a stone – if this incident did occur, the Lammergeier must be a likely candidate for the “eagle”.

The black and white photo of the very vulturine Dragon Bridge is by Barbara Meadows.