Couch’s spadefoots: Tons of tiny toadlets!

My friend Kathy gave me a bucket of toads. Twenty five tiny toads, actually Couch’s spadefoots (Scaphiopus couchii) to be precise. Spadefoots are toadlike amphibians, with their own family, Pelobatidae (see etymological note below). They’re native to the Sonoran desert, and their reproductive cycle is timed to take advantage of summer monsoon rains, needing only 7-8 days to go from egg to tadpole to toadlet. In between monsoon seasons, the adults stay buried deep in the soil of sandy washes to keep from drying out. They can stay buried for 8-10 months at a time, until storms bring the right conditions for them to feed and breed. The sheep-like bleating

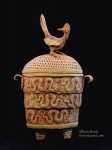

My friend Kathy gave me a bucket of toads. Twenty five tiny toads, actually Couch’s spadefoots (Scaphiopus couchii) to be precise. Spadefoots are toadlike amphibians, with their own family, Pelobatidae (see etymological note below). They’re native to the Sonoran desert, and their reproductive cycle is timed to take advantage of summer monsoon rains, needing only 7-8 days to go from egg to tadpole to toadlet. In between monsoon seasons, the adults stay buried deep in the soil of sandy washes to keep from drying out. They can stay buried for 8-10 months at a time, until storms bring the right conditions for them to feed and breed. The sheep-like bleating of the singing male spadefoot is an archetypal sound of the Sonoran desert. Some Arizona tribes associate toads and owls with monsoon rain, and that’s the origin of the fanciful Three Star Owl piece “Two-Toad Owl“.

of the singing male spadefoot is an archetypal sound of the Sonoran desert. Some Arizona tribes associate toads and owls with monsoon rain, and that’s the origin of the fanciful Three Star Owl piece “Two-Toad Owl“.

These little spadefoots hatched in a standing pool in Kathy’s Scottsdale yard, where they’re plentiful. They’re very tiny — each could sit on a penny. They’re so small that it wasn’t until I saw the close-up photos that their emerald green eyes were noticeable. If you’ve never nourished toadlets, they’re easy to feed: if it moves and fits in the toadlet’s mouth, they’ll eat it. These guys have been snarfing up crickets, and other protein-rich yummies like Miller moth larvae from birdseed (and an old bag of flour!).  Even ants will go down the hatch, as long as it’s not one of the larger soldiers, which put off a noxious chemical. The one on the left was photographed before the first cricket feeding; it plumped up noticeably after downing a small cricket or two.

Even ants will go down the hatch, as long as it’s not one of the larger soldiers, which put off a noxious chemical. The one on the left was photographed before the first cricket feeding; it plumped up noticeably after downing a small cricket or two.

But I’m not keeping them in captivity. Once they’re fed up, I’ll release them in our yard at twilight, where hopefully they’ll replenish our neighborhood population. Releasing them after dark will give them a head-start over the foraging Curve-billed thrashers and Cactus Wrens. A couple years ago, we would hear male spadefoots bleating like lambs after a big rainstorm, and one or two would end up in the pool, looking for somewhere to breed. But recently, we haven’t heard or seen any. So I’m hoping these guys get things going again. Good luck, little spadefoots, and ‘ware Raccoons and Coachwhips!

Photos: the adult spadefoot photo is from the US Fish & Wildlife site on Arizona Amphibians. The other photos are by A. Shock. Excellent photos and still more info about Couch’s spadefoot can be found at Firefly Forest — check it out.

Etymolgical note and stray ornithological note

About the term “spadefoot”: It comes from the small, hard digging appendage on the underside of the back legs of these amphibians. Members of the family Pelobatidae are not considered “true” toads, so it’s proper to call them simply “spadefoots”. Pelobatidae, the family name for all Spadefoots, comes from a Greek word, pelobates (πηλοβατης), literally “mud-walker”. A nice tie-in for a potter is that the first element of this word comes from the Greek word pelos, meaning “clay”, specifically the clay used by potters and sculptors.  The genus, Scaphiopus, is constructed of two Greek elements and means “spade-foot”. The species name, couchii, comes from the surname of Darius Nash Couch, a U.S. Army officer who, during leave in 1853/54, traveled as a Smithsonian Institute naturalist to Mexico, where he collected specimens of both the Couch’s Spadefoot, and Couch’s Kingbird, a tyrant flycatcher native to south Texas and the gulf coast of Mexico. Out-of-range Couch’s kingbirds occasionally show up in Arizona. Recently, a Couch’s kingbird has wintered in Tacna in southwest Arizona, eating bees and behaving like a tyrant flycatcher.

The genus, Scaphiopus, is constructed of two Greek elements and means “spade-foot”. The species name, couchii, comes from the surname of Darius Nash Couch, a U.S. Army officer who, during leave in 1853/54, traveled as a Smithsonian Institute naturalist to Mexico, where he collected specimens of both the Couch’s Spadefoot, and Couch’s Kingbird, a tyrant flycatcher native to south Texas and the gulf coast of Mexico. Out-of-range Couch’s kingbirds occasionally show up in Arizona. Recently, a Couch’s kingbird has wintered in Tacna in southwest Arizona, eating bees and behaving like a tyrant flycatcher.