Increments: Color me vulture, finally

Here are the exciting final steps of Jack’s King Vulture. (Previous increments can be viewed and read about here.)

This first photo, Increment 3, is a close-up of what the piece looks like after it’s been bisqued (fired the first time) and then glazed. Pretty crappy looking, isn’t it? That’s because glaze is a chalky-looking liquid suspension made of clay, mineral pigments and oxides, a flux or glassy component to create various levels of gloss after melting, plus water. If Pepto Bismol came in a lot of different icky-pale flavors, they would look like glazes. Because of this, glazing a piece you’ve already spent hours on can be an act of faith, and once the raw glazes are on, it’s often hard to escape the feeling that now you’ve gone and ruined it, which sometimes you have. Fortunately the more you glaze, the better able you are to predict what the chalky colors will look like after firing, so the more you trust the materials and the process (=faith, for a potter). It’s only after the final firing that the glaze colors take on any kind of brightness and glassy quality. Here is Increment 4, Jack’s finished King Vulture, Sarcoramphus papa, photographed in the wilds of Scottsdale:

Pretty crappy looking, isn’t it? That’s because glaze is a chalky-looking liquid suspension made of clay, mineral pigments and oxides, a flux or glassy component to create various levels of gloss after melting, plus water. If Pepto Bismol came in a lot of different icky-pale flavors, they would look like glazes. Because of this, glazing a piece you’ve already spent hours on can be an act of faith, and once the raw glazes are on, it’s often hard to escape the feeling that now you’ve gone and ruined it, which sometimes you have. Fortunately the more you glaze, the better able you are to predict what the chalky colors will look like after firing, so the more you trust the materials and the process (=faith, for a potter). It’s only after the final firing that the glaze colors take on any kind of brightness and glassy quality. Here is Increment 4, Jack’s finished King Vulture, Sarcoramphus papa, photographed in the wilds of Scottsdale:

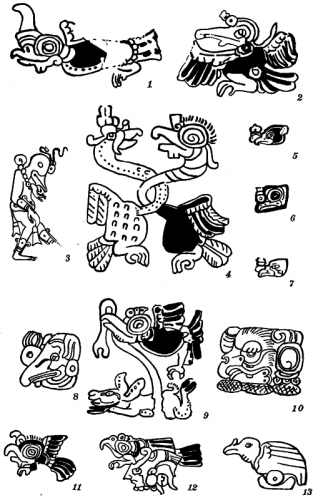

Check out the pale eye, it’s not a mistake: the King Vulture’s iris is white, which to our eyes looks pretty weird. In Mayan glyphs King Vultures are readily identifiable not only by the fleshy knob or caruncle atop their strong, hooked beak, but also by the bold concentric depiction of the staring white eye. Below is a plate from Animal Figures in the Maya Codices by A.M. Tozzer and G.M. Allen (1910) that shows a selection of Mayan King Vulture glyphs. Of course, I’m not an expert, but Tozzer and Allen report that the King Vulture represents Cib, the 13th day of the month. And, on an ornithological note, figure 4 in the plate below shows a King Vulture entwining necks with an Ocellated turkey, the turkey of the Maya, which puts our Wild Turkey of North America to shame in terms of colorful plumage and warty wattly facial skin, which is saying something. I photographed the Ocellated turkey below at Chan Chich in Belize, where they inhabit the immediate area along with King Vultures, like the one in a previous post who tried to hide behind a leaf.

By the way, if you live in the Phoenix area, there are two King Vultures on display in a large aviary at the Phoenix Zoo. You could drop in any time to visit them. E and I just did, on Valentine’s Day. I guess we missed Cib by one day!

By the way, if you live in the Phoenix area, there are two King Vultures on display in a large aviary at the Phoenix Zoo. You could drop in any time to visit them. E and I just did, on Valentine’s Day. I guess we missed Cib by one day!

Increments: Color me vulture (Sarcoramphus papa), plus a quick field trip to Belize

Another reason I’ve had vultures on the brain is because I owe a friend a vulture. Specifically, a king vulture, Sarcoramphus papa, the largest of the Cathartids, the New World Vultures. They are the largest vulture in our hemisphere if you don’t count the two condors, and they are striking birds (literally — I was given a hammery-beaky once-over by one in captivity long ago, but that’s a different post), with black-and-white plumage and a bare-skinned, froot-loops colored head roped with chicken-skin folds. If that weren’t enough, both genders sport a caruncle on the top of their bills: a warty, fleshy, bright orangey-yellow knob whose purpose, frankly, I don’t know, if not to gild the lily.

So, here is Jack’s King vulture, in progress, Increment 1. Having modeled the bird, it awaits slip, with a photo behind for plumage color reference. I’ll give it a base coat of slip (“paint” made of clay, mineral colorants, and water) in appropriate colors while the stoneware is still damp. Once it is completely dry, it will go into its first (or bisque) firing. After that it’ll get glazes and other finishing colorants applied, and be fired again.

So, here is Jack’s King vulture, in progress, Increment 1. Having modeled the bird, it awaits slip, with a photo behind for plumage color reference. I’ll give it a base coat of slip (“paint” made of clay, mineral colorants, and water) in appropriate colors while the stoneware is still damp. Once it is completely dry, it will go into its first (or bisque) firing. After that it’ll get glazes and other finishing colorants applied, and be fired again.

As usual with clay, the heaviness of the material requires support, so I’ve had to fudge some physical realities: I can’t make the legs as thin as they are in nature, and I’ve used the wings as the third point of support so the bird stands by itself. Normally, a vulture’s wings, as ample as they are, don’t reach the ground in a standing bird. But other typical characteristics will carry the likeness through: the hunched posture, the partially opened wings, the body plumage color, and of course, pleated froot-loop head.

Increment 2: Slip treatment. In this case, the slips were applied with a brush. They will not acheive their finished colors until the final Cone 5 firing. For now, the black looks brown and the white looks grayish. The froot loop colors will be applied as glazes, after bisquing. Now this guy will sit until he’s TOTALLY dry. Also, his body is hollow, and this time I did remember to pierce an inconspicuous hole to the cavity. Stay tuned for later posts for finishing touches.

Increment 2: Slip treatment. In this case, the slips were applied with a brush. They will not acheive their finished colors until the final Cone 5 firing. For now, the black looks brown and the white looks grayish. The froot loop colors will be applied as glazes, after bisquing. Now this guy will sit until he’s TOTALLY dry. Also, his body is hollow, and this time I did remember to pierce an inconspicuous hole to the cavity. Stay tuned for later posts for finishing touches.

Most of us think of vultures as being all-dark birds, like Turkey vultures. But there are predominantly white vultures, like the King. In the Old World, the Egyptian vulture, also a vulture primarily of hot climates, is mostly white-plumaged. You would think a large white bird would be disadvantaged by being easily seen. Actually, King vultures, when roosting and nesting in their tropical forest habitat, are surprisingly difficult to see. Their white feathers reflect the green light passing through the foliage around them, making them blend in quite well. They are somewhat shy despite their regal reputation, and tend to assume a self-effacing posture when perched on a limb. A King vulture in Belize “hid” from us this way. We spotted it on the ground in a field. Feeling our “eyeball pressure” it felt safer flying up into a tree, where it hid its head behind a tiny clump of foliage. The rest of its enormous body remained in plain sight, but it felt better, and would peek out from the leaves occasionally to see if we were gone yet.

In the air, an all-white bird glints in the sun, but of course, up there, they’re out of reach, especially at the altitudes King vultures acheive. It’s a spectacular sight to see the bright wedge of a King, as white and as large as a pelican, rising on thermals over a mahogany forest. The photo below is of just such a Belizean forest as a King vulture would favor. Imagine one soaring just out of frame, with Bat falcons, Swallow-tailed kites, White hawks and other tropical birds of prey swirling on the updrafts from the Escarpment near Chan Chich, one of the few places in that flat country where you can get out and up over the forest.

Stacked Toad effigy vessel part 3, also why is a toad not a frog?

There have been many delays and distractions for the Stacked Toad Effigy Teapot: computer failure and restoration, other deadlines, and Thanksgiving, including a tragic Saguaro Plunge, details to be posted later.

But here is the next phase: the “lid” of the “teapot” is in place, and also the “finial” (knob), with Hector Halfsquid for scale.

But here is the next phase: the “lid” of the “teapot” is in place, and also the “finial” (knob), with Hector Halfsquid for scale.

This involved the addition of more toads — the final toads — to represent the top of the “teapot”. The visual theme is toads-upon-toads, stacks of toads, piles of toads. During the Couch’s spadefootlet episode, I was reminded of the toadly practice of Climbing On Your Neighbors. When kept in captivity in large numbers, toads (and other amphibians and reptiles) will climb on each other with no regard for personal space, or any politeness at all. I wanted to capture this “toe-in-the-eye” sense of physical involvement in the Toad Stack. So on went two more toads, atop the base grouping of four toads. Despite more than a week having elapsed this was not a problem, because even in the desert clay can be kept workable if enough dry-cleaners’ plastic and moist towels are employed. On the right is a shot of damp paper towels swathing the heads of the toads; they will need to be textured at some point, and if they’re too hard, it won’t work and the moist towels keeps the clay pliable and soft enough to receive an impression.

On the right is a shot of damp paper towels swathing the heads of the toads; they will need to be textured at some point, and if they’re too hard, it won’t work and the moist towels keeps the clay pliable and soft enough to receive an impression.

The effect of the two new toads, striving against each other on top of the pile, was what I wanted, but they needed a focal point — a flying insect they’re both trying to swallow. This was the finial, or knob, of the “teapot” “lid”:

At this point, I always feel a piece is almost finished: the basic elements are sculpted and in place, there are at the moment no structural crises to solve. But it’s far from the truth: a lot still remains to be done — texturing, refining shape detail (toes!), cleaning up stray clay bits and meaningless marks, applying decorative slip, etc. For instance, I’ve forgotten until now about parotoid glands, which will have to be added. And, other time-consuming details like compound eyes on the flying prey item. So stay tuned for the next post on the effigy teapot: Texturing the Toad.

(Potential Toe Count: 104; Actual Toe Count: 49 so far; current Biological Digit Deficit, 53%)

Increments so far:

Why is a toad not a frog?

You almost certainly know this, but a toad isn’t a frog.

If that came as a surprise, it’s time for a speedy round-up of amphibian facts:

In general: toads have dry warty skin, frogs have moist slick skin. Toads need little or no water except to breed; frogs are usually amphibious. Toads have large kidney-shaped swellings behind each eye called parotoid glands; frogs have round hearing-related structures called tympani behind each eye. Most people think toads are gross but frogs are cute. That isn’t science; it’s just bad taste. Frogs croak, but many toads like Woodhouse’s toads have beautiful muscial trills. ( If you were a Woodhouse’s toad, you’d think that was beautiful…) Toads have stout compact bodies with short legs for hopping; frogs are often svelte and long-legged for leaping. Most frogs have webbed feet, most toads are not or only partially web-footed. Frogs are more inclined to climb; toads are more inclined to dig. Both can secrete irritating or even poisonous compounds that deter predators.

Toads have stout compact bodies with short legs for hopping; frogs are often svelte and long-legged for leaping. Most frogs have webbed feet, most toads are not or only partially web-footed. Frogs are more inclined to climb; toads are more inclined to dig. Both can secrete irritating or even poisonous compounds that deter predators.

To the right above is a photo of a Ramsey Canyon Leopard Frog being aquatic. Contrast it with the photo below it, a tropical toad from Belize. (photos, A. Shock)

In fact, these distinctions are generalizations and don’t hold true for every frog or toad. For more detail, I recommend the Dorling-Kindersley Eyewitness book Amphibian, by Dr. Barry Clarke. It’s meant for kids, but it’s really all anyone but a real herpetologist needs to get the gist of of toads, frogs, and caecilians.

Stacked Toad Effigy Vessel: part 2

The Stacked Toad Effigy Vessel is being built from the bottom up, with a brown, groggy, stoneware clay. The working composition is in my head, informed by pictures of desert toads on the work bench, and adapted as it goes. A small maquette modeled last week is nearby for reference, although the maquette has species other than toads in it as well. The Toad Stack is on the scale of a teapot, so in addition to being a Toad Effigy, it could be considered a Teapot Effigy as well: a vessel in the shape of a teapot, if your concept of teapot is broad. Perhaps it will be a Stacked Toad Teapot Effigy.

The Base Toad was modeled solid, allowed to set up to a manageable firmness, then hollowed out and slightly expanded in size by pinching. When firm enough, each limb was cut off one at a time, and a tool was inserted up the center to create a tunnel, then the limb was scored and slipped back into place. The smaller toadly elements are pinched informally into toadly shapes. Each new toad is added when the clay has “set up” — when it’s stiff enough to hold its shape, but still pliable enough to conform to the surface it rests on, and also support the next element. TOES are beginning to appear (Potential Toe Count: 72; Actual Toe Count: 19 so far; current Biological Digit Deficit, 73.5%). Because the interior is hollow, there are a couple of small invisibly placed outlets for air to escape. This speeds drying and will allow the piece to be fired without exploding as the heating internal air expands. When all toadly elements have been added, the surface will be textured in a toadly manner: bumps, bugs, and paratoid glands.

The Base Toad was modeled solid, allowed to set up to a manageable firmness, then hollowed out and slightly expanded in size by pinching. When firm enough, each limb was cut off one at a time, and a tool was inserted up the center to create a tunnel, then the limb was scored and slipped back into place. The smaller toadly elements are pinched informally into toadly shapes. Each new toad is added when the clay has “set up” — when it’s stiff enough to hold its shape, but still pliable enough to conform to the surface it rests on, and also support the next element. TOES are beginning to appear (Potential Toe Count: 72; Actual Toe Count: 19 so far; current Biological Digit Deficit, 73.5%). Because the interior is hollow, there are a couple of small invisibly placed outlets for air to escape. This speeds drying and will allow the piece to be fired without exploding as the heating internal air expands. When all toadly elements have been added, the surface will be textured in a toadly manner: bumps, bugs, and paratoid glands.

Useful tools: teaspoon and loop tool for hollowing; palette knife and small knife; Tiranti hardwood sculptural tools knobbed at one end and pointed at the other for smoothing internal seams and detailing; toothed metal rib; smooth plastic rib; cheap blow dryer for force-drying clay; wooden paddle made by L.

Useful tools: teaspoon and loop tool for hollowing; palette knife and small knife; Tiranti hardwood sculptural tools knobbed at one end and pointed at the other for smoothing internal seams and detailing; toothed metal rib; smooth plastic rib; cheap blow dryer for force-drying clay; wooden paddle made by L.

Our autumnal weather has slowed drying time, so there are lots of gaps in toadly modelling activity while waiting for wet clay to set up. These times are spent in making the next toads, working on other pieces, or going out for excellent sushi at Dozo. In order to prevent the Stack of Toads from settling under its own weight, it will stay loosely wrapped in plastic until tomorrow, with a smooth river cobble wedged under its left front limbpit to help support it until work can resume. What will the Toad Total be?