The last post was about really big mammals that seem on a scale with mammoths, condors, and whales. That’s the thing about the Western US, you can never be sure when you’re going to run into some immense mammal, left over from the Ice Age:

E does field work in Yellowstone, so I have an acquaintance with relict Pleistocene megafauna. Once when we were at a back-country hot spring taking measurements, someone stood up and said, “What’s that?” Everyone stood up and looked, and saw a Grizzly Bear. I stood up too, but the autumn grass was tall, and all I could see was a brown woolly hump lurching closer. It could have been anything, a moose, an elk, a ranger. But it was a bear, scavenging old bones where bison had gone to die on a warm thermal hillside. That’s when I realized how effectively height is selected for in humans.

It’s easy to be afraid of a grizzly bear, but it’s smart to be afraid of a Bison. Even if you know how fast and big they are, they’re actually even bigger than that, and much faster. Not long ago I ran into one, n ot in Yellowstone, but on Catalina Island, on a hike up to Butt Hill (its real name) above Two Harbors. I was alone, coming down a “social trail” — an informal path made by people’s feet

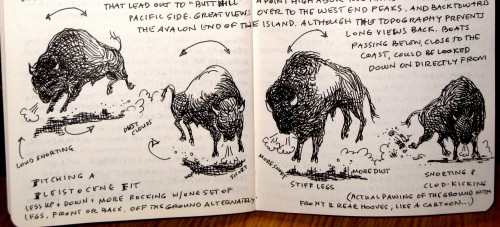

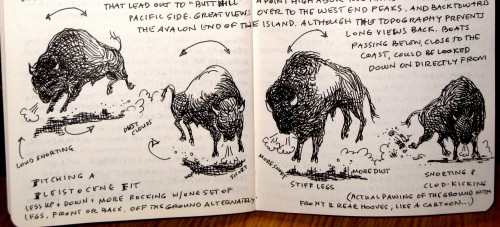

ot in Yellowstone, but on Catalina Island, on a hike up to Butt Hill (its real name) above Two Harbors. I was alone, coming down a “social trail” — an informal path made by people’s feet  rather than Park Employees’ shovels — and as I came out of a shrubby oak woods (see photo on right) onto the official road from above, a Bison came out in the same place from below. He was headed up hill, up the trail I had just come down, and was Not At All Pleased to see me. He began to snort, and kick clods, and in general act like a Warner Bros. cartoon bull, except not funny a bit. I sidled up to a shrubby little oak with spreading branches figuring I could climb if it came to that. The bison was only about 15 feet away, so I held very still. After more macho display, he moved off a short distance. But then I moved slightly, and it set him off again, scuffling dirt and huffling snort and hopping around rocking back and forth, wagging his huge bearded head over his fore-hooves, like an owl “toe-dusting”. The problem was that he had moved off down hill, where I needed to go, and I was standing where he wanted to go. All I could do was hold still until he stopped doing Crabby Boss-man Dance, imagining being late for dinner at the conference dining hall, which seemed very very very far away from that scrubby oak woods, trying to not think what a bison horn would feel like hooked under the ribs.

rather than Park Employees’ shovels — and as I came out of a shrubby oak woods (see photo on right) onto the official road from above, a Bison came out in the same place from below. He was headed up hill, up the trail I had just come down, and was Not At All Pleased to see me. He began to snort, and kick clods, and in general act like a Warner Bros. cartoon bull, except not funny a bit. I sidled up to a shrubby little oak with spreading branches figuring I could climb if it came to that. The bison was only about 15 feet away, so I held very still. After more macho display, he moved off a short distance. But then I moved slightly, and it set him off again, scuffling dirt and huffling snort and hopping around rocking back and forth, wagging his huge bearded head over his fore-hooves, like an owl “toe-dusting”. The problem was that he had moved off down hill, where I needed to go, and I was standing where he wanted to go. All I could do was hold still until he stopped doing Crabby Boss-man Dance, imagining being late for dinner at the conference dining hall, which seemed very very very far away from that scrubby oak woods, trying to not think what a bison horn would feel like hooked under the ribs.  Eventually he stopped acting thuggish (I swear it felt like an hour, but it was probably only a couple of minutes), then he moved off behind some trees, uphill, and disappeared. I stuck to the crummy oak for a few more minutes and then picked my way down hill, on the downhill side of the trail, saying intelligent-sounding things like “Ho, bison,” and “Hey, bison,” so it would know I was there and not be surprised. The rest of the hike was treeless, and I kept looking over my shoulder for the big angry animal, but I never saw it again.

Eventually he stopped acting thuggish (I swear it felt like an hour, but it was probably only a couple of minutes), then he moved off behind some trees, uphill, and disappeared. I stuck to the crummy oak for a few more minutes and then picked my way down hill, on the downhill side of the trail, saying intelligent-sounding things like “Ho, bison,” and “Hey, bison,” so it would know I was there and not be surprised. The rest of the hike was treeless, and I kept looking over my shoulder for the big angry animal, but I never saw it again.

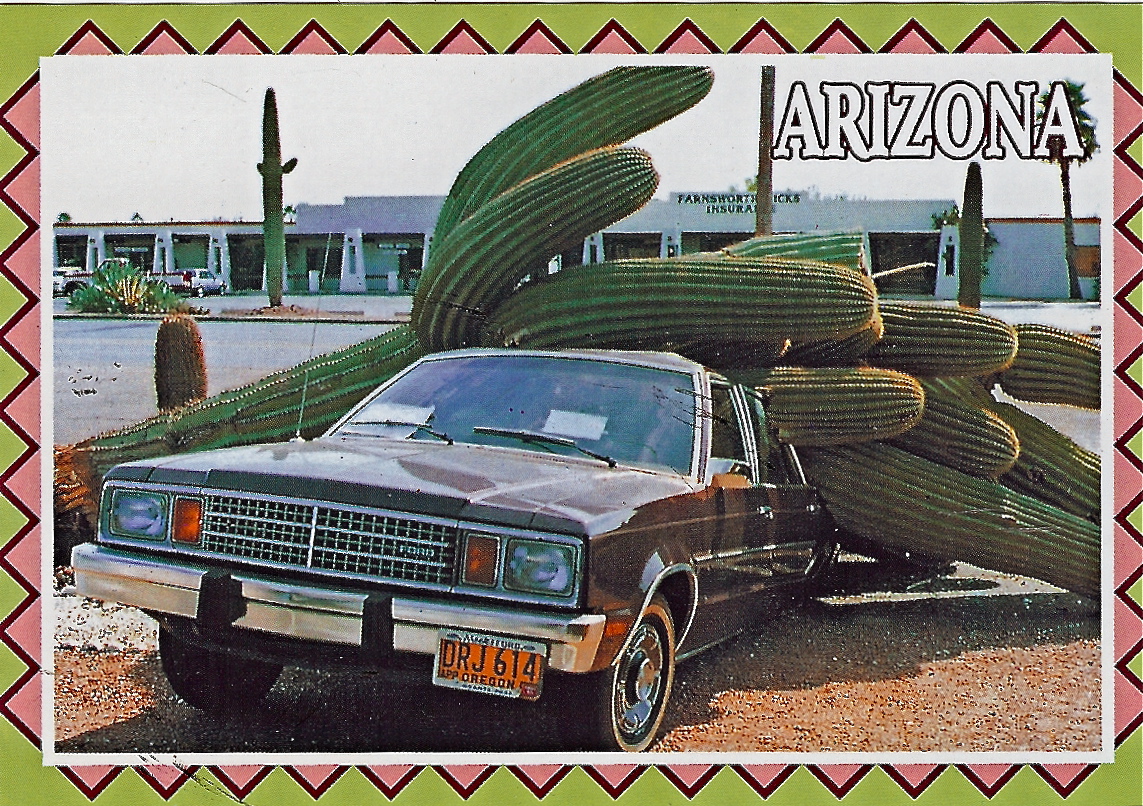

Bison aren’t supposed to be on Catalina Island, but like a lot of things living in Southern California, they were left behind by a film crew. In 1924, so the story goes, 14 bison imported to the island for a film version of Zane Grey’s “Vanishing American” were left to fend for themselves. They did, for better or worse. To judge by the number of close-call videos posted on You Tube, I’m not the only one who’s had an adventure with one of them. I didn’t get photos: the last thing on my mind at the time was the camera. So my only record of the actual encounter is the Fauxtograph and sketches from my journal included here. (The very telephotic picture just above shows a bison at a distance — probably the same one I ran into later, but I never imagined he’d cover so much terrain so quickly. He’s the brownish deceptively tiny blob in the brightest green patch of grass, lying down calmly chewing cud.)

Bison aren’t supposed to be on Catalina Island, but like a lot of things living in Southern California, they were left behind by a film crew. In 1924, so the story goes, 14 bison imported to the island for a film version of Zane Grey’s “Vanishing American” were left to fend for themselves. They did, for better or worse. To judge by the number of close-call videos posted on You Tube, I’m not the only one who’s had an adventure with one of them. I didn’t get photos: the last thing on my mind at the time was the camera. So my only record of the actual encounter is the Fauxtograph and sketches from my journal included here. (The very telephotic picture just above shows a bison at a distance — probably the same one I ran into later, but I never imagined he’d cover so much terrain so quickly. He’s the brownish deceptively tiny blob in the brightest green patch of grass, lying down calmly chewing cud.)

Nature is unpredictable: the next day I came down with a horrible cold. I’d been worried about being gored on the spot, but instead I was laid low by a bacterium or virus, and was miserable for days. I’ll bet the bison never even gave the incident a second thought.

In memoriam: favorite rust-colored bandanna lost at some point during the escape, when it fell out of a pocket. On the other hand, I ask: is it smart to hike in bison country with a reddish flag wafting at your side?…

In memoriam: favorite rust-colored bandanna lost at some point during the escape, when it fell out of a pocket. On the other hand, I ask: is it smart to hike in bison country with a reddish flag wafting at your side?…

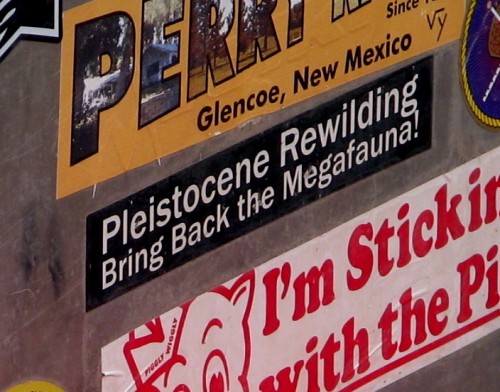

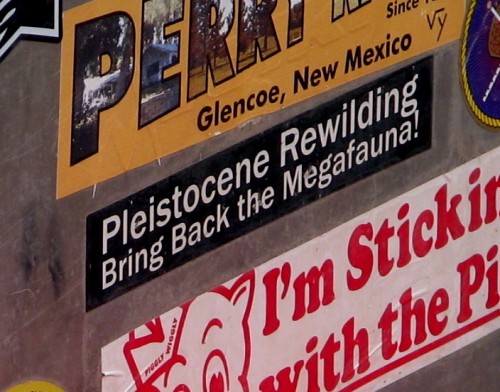

Photos: A. Shock. Yes, it’s a plastic bison. That’s the fauxtograph. Left: bumper sticker on the gear box of a Colorado River raft. I’m sure the Condors would appreciate Pleistocene rewilding, too. I’m not so positive: Bison are bad enough, but Short-faced bear and Smilodon? Don’t know about hiking with those guys…

Pleistocene megafauna trivia

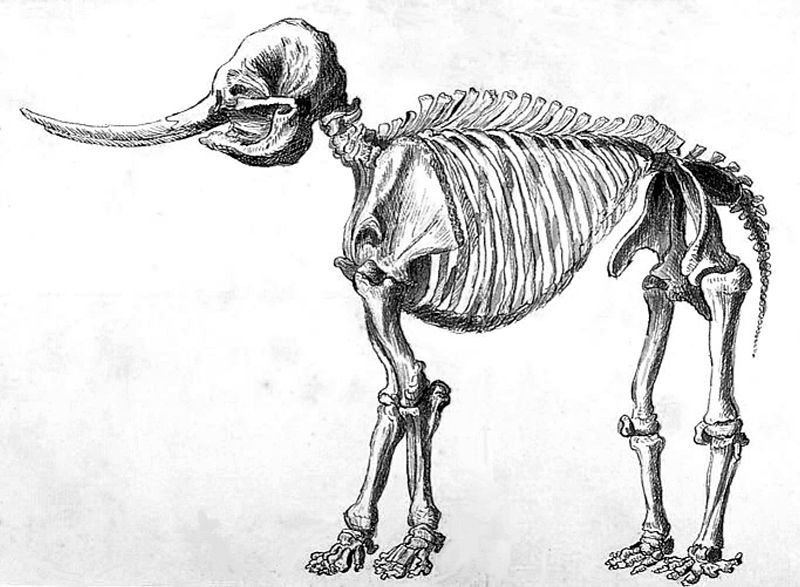

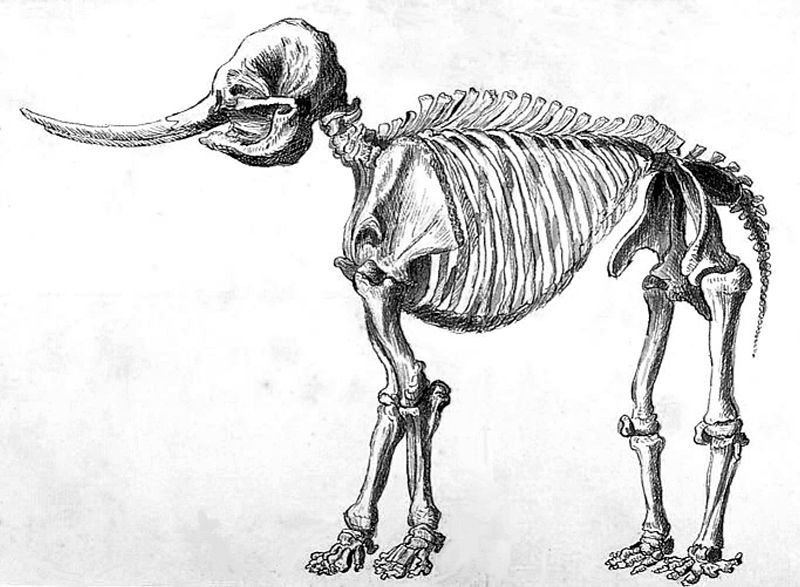

It’s a fact that Lewis and Clark were told to look for  Mastodon dead or living on their exploratory jaunt out West, because the terrain was little enough known that the cognoscenti

Mastodon dead or living on their exploratory jaunt out West, because the terrain was little enough known that the cognoscenti  back East weren’t absolutely SURE they were extinct. Besides, Thomas Jefferson (right, B&W) wanted to prove wrong the eminent French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (right, in color) who claimed that the degenerate North American environment couldn’t support a robust fauna (including its humans). Jefferson was a big fossil enthusiast, and had a relatively new shiny country to defend against Old World criticism of not coming up to snuff. To refute Buffon’s claim, so the story goes, he dispatched US soldiers into the north woods to shoot a bull moose to ship to France for display, but Jefferson felt it was necessary to substitute a more impressive rack from another individual to bolster his case that the fauna of North America was indeed macho.

back East weren’t absolutely SURE they were extinct. Besides, Thomas Jefferson (right, B&W) wanted to prove wrong the eminent French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (right, in color) who claimed that the degenerate North American environment couldn’t support a robust fauna (including its humans). Jefferson was a big fossil enthusiast, and had a relatively new shiny country to defend against Old World criticism of not coming up to snuff. To refute Buffon’s claim, so the story goes, he dispatched US soldiers into the north woods to shoot a bull moose to ship to France for display, but Jefferson felt it was necessary to substitute a more impressive rack from another individual to bolster his case that the fauna of North America was indeed macho.

To come back full circle to our bison, it has a prominent place in a monograph Jefferson wrote in response to Buffon’s claim that America was a land “best suited for insects, reptiles, and feeble men.” Jefferson pointed out that quadrupeds occurring only in America not only out-number by four to one quadrupeds unique to Europe, but that one of them by itself, the American Bison, actually outweighs all of the indigenous European quadruped species combined!

Left: Peale’s mastodon, the critter that everyone was talking about in 1803.