Cranky Owlet finally meets…

…a true kindred spirit:

Adult Burrowing owl giving the entire world StinkEye at the Adobe Mountain Wildlife Center display at Boyce Thompson Arboretum‘s “Welcome Back Buzzards Day”. (Photo A.Shock)

Adult Burrowing owl giving the entire world StinkEye at the Adobe Mountain Wildlife Center display at Boyce Thompson Arboretum‘s “Welcome Back Buzzards Day”. (Photo A.Shock)

Episode 1

During this session the staff once again permitted me to sketch the objects only with dry media, so I brought graphite pencils and a kneaded eraser, which does not produce erasure pills. This made it necessary to add colors later with watercolor, from memory, since photos are not allowed, either. During the appointment the objects — elevated on a black velvet cushion — stayed on the other side of the table, as did the librarian, who turned them for me if I required to see the back, or a profile. She wore bright purple non-latex gloves, like a medical technician drawing blood, to keep finger oils and sweat off of the surfaces.

The descriptions below are my personal non-technical notes, observations both descriptive and ornithological (to the extent possible), made to assist me in capturing the quality of the surfaces later. The Library Catalog entries for these objects include blurry, low-contrast black-and-white photos, with only brief notations of dimension, and accession date and source where known; very few have these. The uncredited author uses the word “fetish” to refer to all of the smaller owls, probably because of their size and three-dimensional form. There is no actual evidence of ritual use or function. Note: scale of objects is approximate since I was not allowed to touch the objects to obtain measurements. Therefore, dimensions given are maximum in any axis, as stated in the Library Catalog.

The fact that these “fetishes” depict “eared”-type owls does not help to pin-point their origins. There are owls with cranial tufts on nearly every continent belonging to, for example, both the large (Bubo) and the small (Scops) genuses.

Again, my thanks to the Ganskopf Foundation for allowing me access to the collection in order to illustrate these enigmatic pieces and the permission to reproduce them here, and special thanks to librarian Leyla Laguna. The images here are the property of the Ganskopf Collection and may not be produced without written permission.

Again, my thanks to the Ganskopf Foundation for allowing me access to the collection in order to illustrate these enigmatic pieces and the permission to reproduce them here, and special thanks to librarian Leyla Laguna. The images here are the property of the Ganskopf Collection and may not be produced without written permission.

From the middle of the day yesterday until just after 10pm, a big wind storm ruffled the Phoenix area. It made the blustery afternoons we’ve been having look like a gentle breeze. There were sustained winds near 30mph, and a peak wind gust of 53mph. Much of this was after dark, and the Aleppo pine’s thin boughs tossed and snapped, setting off the motion detector light in the back yard — in the light we could see the Hen’s slender bough whipping up and down, the nest riding high or low at each gust. To discourage heavier  predators, she’s built the nest in the flexible twigs at the end of a branch, so the motion was maximum and it looked like a wild ride. I was sure it was the end of the nidification, but thanks to several miracles of nature: excellent building skills, parental determination, and pure luck, the Hen and her Nid weathered the storm. For the whole event she sat in the nest, effectively corking it so that the eggs stayed in. E saw her up there during the worst, sitting and being tossed around. It’s hard not to try to imagine what she felt — panic and fear, or the zen-like calm of having no options? Maybe she slept. We can’t know.

predators, she’s built the nest in the flexible twigs at the end of a branch, so the motion was maximum and it looked like a wild ride. I was sure it was the end of the nidification, but thanks to several miracles of nature: excellent building skills, parental determination, and pure luck, the Hen and her Nid weathered the storm. For the whole event she sat in the nest, effectively corking it so that the eggs stayed in. E saw her up there during the worst, sitting and being tossed around. It’s hard not to try to imagine what she felt — panic and fear, or the zen-like calm of having no options? Maybe she slept. We can’t know.

We assume the eggs survived as well, as she is still very tight today. It’s an amazing thing.

No picture of the Hen this morning, but the photo above is what the strength of the winds did nearby in our yard: a section of fencing blew down, nails ripped right out of wood, flattening annuals and a couple of shrubs. Amazing that a tiny two-inch nest survived what a fence couldn’t. Now, if only we could borrow a tool from the Hen’s repertoire and use spider web to stick the fence back up…

One of my favorite places to go in the Phoenix area at any time of year (except perhaps in the heat of summer) is the Boyce Thompson Arboretum. It’s a botanical garden of native and non-native desert plants up in the desert mountains around Superior Arizona about an hour’s drive east of Phoenix. It’s spectacularly sited along craggy Queen Creek gorge at the foot of Picketpost Mountain. And it’s great for plants, birds, walking, picnicking — even shopping, like now when their twice-annual plant sale is going on. If this sounds like an ad, that’s okay, I’m happy to enthuse about the place.

One of my favorite places to go in the Phoenix area at any time of year (except perhaps in the heat of summer) is the Boyce Thompson Arboretum. It’s a botanical garden of native and non-native desert plants up in the desert mountains around Superior Arizona about an hour’s drive east of Phoenix. It’s spectacularly sited along craggy Queen Creek gorge at the foot of Picketpost Mountain. And it’s great for plants, birds, walking, picnicking — even shopping, like now when their twice-annual plant sale is going on. If this sounds like an ad, that’s okay, I’m happy to enthuse about the place.

We made a visit earlier this week: the place is rocking with wildflower color, the penstemons are at their peak, and the aloes are still going; the spring migrant birds are coming in and the residents are singing and nesting like mad. For some reason, male Costa’s hummingbirds — sturdy little desert hummers with bright purple mustaches (in the right light*) — are particularly in evidence; the hens are probably on their nests now. Here are three images E captured of male Costa’s intently working over various penstemon blooms.

Here are three images E captured of male Costa’s intently working over various penstemon blooms.

Three upper photos by E. Shock. Remember to click on each for a slightly larger image.

Hen update: The Stalwart Hen (who you will recall is an Anna’s Hummingbird) is sitting tighter than ever on her tidy nest atop pine cones in the big Aleppo pine. The breezy air has rearranged the branches around her, and although it’s still easy to see her on the nest, it’s tougher than ever to get photos. But, she’s there.

Speaking of Costa’s hummingbirds and hummingbirds in the yard, I regret to report that we are currently not seeing Miss Thang, the female Costa’s who’s been so regular in our front garden. There is one male Costa’s very actively performing display flights on the edge of the property, but he’s currently the one Costa’s individual who we know has stayed the entire season here. We’re hoping Miss Thang (or a suitable replacement!) will be back sometime around the beginning of June, which is when there seems to be an increase in Costa’s in the yard.

*Here’s a bonus shot of just how purple a Costa’s gorget can look in the right light: it’s a head-on view of a Costa’s at one of our yard feeders (photo A. Shock):

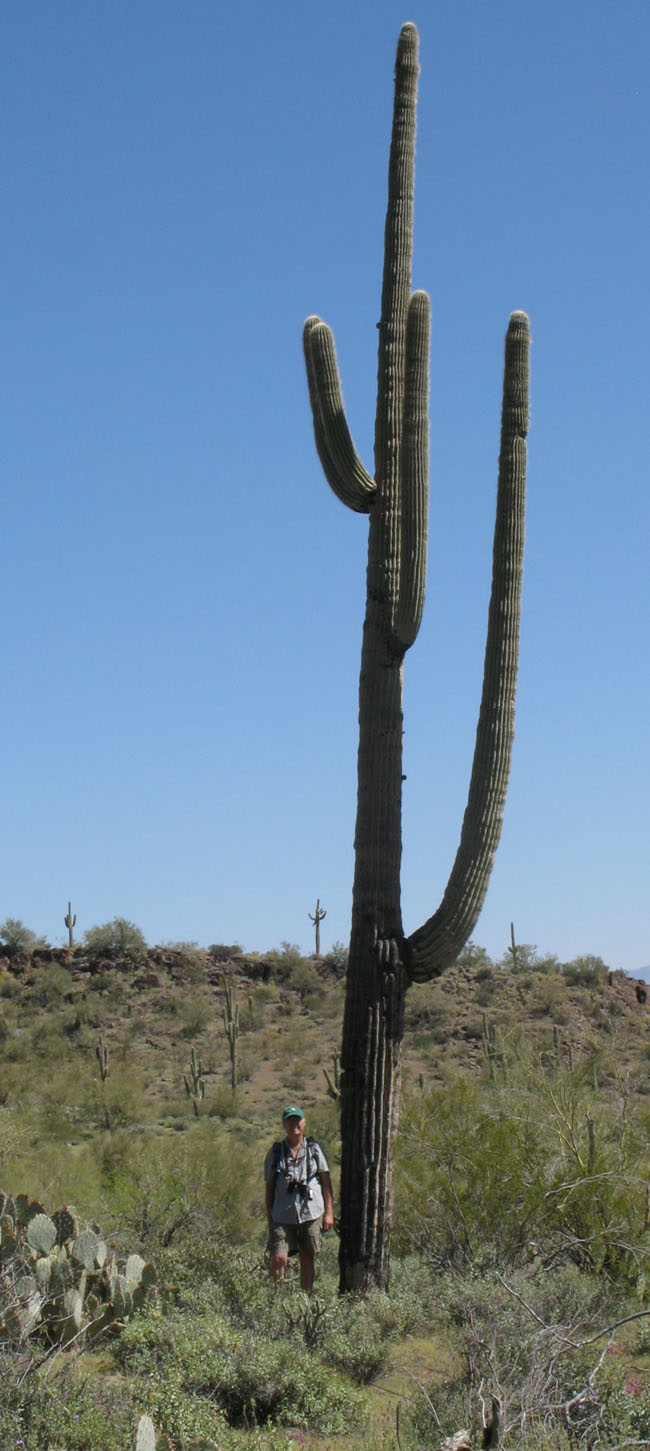

One more post from our desert hike last weekend, because, well — Wow!

One more post from our desert hike last weekend, because, well — Wow!

Right along the trail we encountered two specimens of individual cactus that seemed taller than most of their kin. One was a towering, somewhat spindly saguaro. Of course, saguaros are known for their height, but this was one of the tallest I’ve seen personally. Here’s a shot looking up at its crowns from the base. I’ve also included a picture of the saguaro with E, who is just over 6 feet tall. If you figure you could stack about 7 of him to the top of the cactus, it’s probably close to 45 feet tall which is about maximum species height. Maricopa County is the home of one of the state’s champion saguaros which is just over 50 feet in height, but it grows somewhere in Scottsdale. By the way, although this saguaro has probably survived brush fires, the blackened, tough-looking skin on its lower section is more likely bark, developed with age, in place of the smooth green skin we’re used to seeing on younger individuals. When the skin becomes calloused and barky, the spines are no longer as needed for protection against gnawing animals, and they gradually become the vestigial, button-like bumps you can see in the photo above.

about 7 of him to the top of the cactus, it’s probably close to 45 feet tall which is about maximum species height. Maricopa County is the home of one of the state’s champion saguaros which is just over 50 feet in height, but it grows somewhere in Scottsdale. By the way, although this saguaro has probably survived brush fires, the blackened, tough-looking skin on its lower section is more likely bark, developed with age, in place of the smooth green skin we’re used to seeing on younger individuals. When the skin becomes calloused and barky, the spines are no longer as needed for protection against gnawing animals, and they gradually become the vestigial, button-like bumps you can see in the photo above.

The other picture also has E for scale, but that’s not a young saguaro he’s standing next to. It’s a barrel cactus: a compass barrel, Ferocactus cylindraceus,  one of the most commonly encountered barrel cactus in this part of the desert. They’re big barrels, and when you come across an undisturbed cluster of elderly ones, they’re often 4′ to 5′ tall. But this one, with two small ones growing at its base — probably its own seedlings from many seasons past — looks to be more than 8 feet tall, which must approach the maximum height of the species. The only barrel cactus I’ve seen to compete are the famously tall Diguet’s barrels (Ferocactus diguetii) which can reach 4 meters in height. They grow on just a few islands in the Sea of Cortez off the eastern shore of Baja California. Below is a photo of one, but it’s only of average height — no more than 7 feet.

one of the most commonly encountered barrel cactus in this part of the desert. They’re big barrels, and when you come across an undisturbed cluster of elderly ones, they’re often 4′ to 5′ tall. But this one, with two small ones growing at its base — probably its own seedlings from many seasons past — looks to be more than 8 feet tall, which must approach the maximum height of the species. The only barrel cactus I’ve seen to compete are the famously tall Diguet’s barrels (Ferocactus diguetii) which can reach 4 meters in height. They grow on just a few islands in the Sea of Cortez off the eastern shore of Baja California. Below is a photo of one, but it’s only of average height — no more than 7 feet. And check out the tiny tiny bud of a baby barrel coming up at its base: it looks like a tennis ball. How cute is a baby cactus ?

And check out the tiny tiny bud of a baby barrel coming up at its base: it looks like a tennis ball. How cute is a baby cactus ?

All photos A. Shock (except Diguet’s barrel on Santa Catalina Island, by E. Shock), and with no camera tricks, like standing farther from the camera than the subject: no Hogzilla here!

Here are a couple of photos that show two excellent see-through specializations of Turkey vulturedom: the pervious nostril (already discussed here) and an inner protective eyelid called the nictitating membrane. The camera caught the vulture in mid-blink, so the membrane is visible in this photo as a bluish milky cast over the eye of the vulture — if you click to enlarge the photo to the left, you can easily see it, including the leading edge of the inner eyelid, which slides closed toward the back of the eye. Notice that you can faintly see the bird’s pupil through the membrane: if you can see it, it can see you (like a truck-driver’s rear-view mirror). The lower photo shows the membrane fully closed, and the vulture apparently looking through it at something to the left. (Top photo A. Shock; bottom photo E. Shock)

if you click to enlarge the photo to the left, you can easily see it, including the leading edge of the inner eyelid, which slides closed toward the back of the eye. Notice that you can faintly see the bird’s pupil through the membrane: if you can see it, it can see you (like a truck-driver’s rear-view mirror). The lower photo shows the membrane fully closed, and the vulture apparently looking through it at something to the left. (Top photo A. Shock; bottom photo E. Shock)

Most birds have a nictitating membrane (as well as some other animals, like manatees and horned lizards), and in every animal it has the same basic function — to provide a see-through protective lens over the eye which can be deployed during high-risk activities, such as rummaging through a ripe porcupine carcass with a couple of sharp-beaked buddies (in the case of vultures); plunging into a thorny mesquite bosque in pursuit of a road runner (Harris’s hawk); stooping at 100 mph after a mid-air dove (Peregrine falcon); digging in sandy soils, then cleaning and moistening the gritty cornea (horned lizard).

with a couple of sharp-beaked buddies (in the case of vultures); plunging into a thorny mesquite bosque in pursuit of a road runner (Harris’s hawk); stooping at 100 mph after a mid-air dove (Peregrine falcon); digging in sandy soils, then cleaning and moistening the gritty cornea (horned lizard).

Brief etymology: “nictitating” is derived from Latin nictare, to blink.

HEN UPDATE: The Hen is still tight-on-Nid, having weathered yesterday’s quite breezy atmosphere.

Not much larger than the Verdin is another small gray bird of the Sonoran Desert, the Black-tailed Gnatcatcher. A tiny, long-tailed, streamlined bird with a narrow gleaning bill, both sexes sport cool gray plumage, and in breeding season the male has a full black cap. They actively forage for insects in desert vegetation, and are almost always found in pairs since they remain with their mate year-round. (The similar Blue-gray gnatcatcher comes through the desert around Phoenix in migration, but Black-tailed gnatcatchers are permanent residents here.) Like the Verdin and hummingbirds, Gnatcatchers are champion nest-builders, and build complex and neatly constructed nests inside thorny trees and shrubs like Palo Verde and Catclaw acacia. (For more detail, see this life history from the Sonoran Desert Museum website)

On a recent desert hike in the Hell’s Canyon Wilderness west of Phoenix, E and I watched a pair of Black-tailed gnatcatchers nesting, repeatedly disappearing into the interior of a Palo verde just off the trail, only about 4 feet from the ground, which is a typical nest location for these tiny birds. In the branches midway to the trunk we could see the oblong cup-shaped nest they were working on.

They were working on it, but not in the way we first assumed. On closer observation, we realized that although the Gnatcatchers were a nesting pair, they weren’t building the nest we could see — they were robbing from it. Here’s a photo of the male (to the right of the nest) leaving the scene with a bit of white fluff in his beak, on his way to the current construction site somewhere else. A second later, he flew off, but was back for more in less than a minute. The bird and the nest are both very well camouflaged in the gray sticks and twigs spotted with sunlight in the depths of the green-branched Palo Verde tree. (Photo by E. Shock)

They were working on it, but not in the way we first assumed. On closer observation, we realized that although the Gnatcatchers were a nesting pair, they weren’t building the nest we could see — they were robbing from it. Here’s a photo of the male (to the right of the nest) leaving the scene with a bit of white fluff in his beak, on his way to the current construction site somewhere else. A second later, he flew off, but was back for more in less than a minute. The bird and the nest are both very well camouflaged in the gray sticks and twigs spotted with sunlight in the depths of the green-branched Palo Verde tree. (Photo by E. Shock)

And, speaking of camouflage:

Obvious hint: look for the bright black eye. Here’s a bonus if blurry photo of the backyard Anna’s hummingbird hen, from an upper window. During the morning the Nid-bough is in the sun, and when the Hen sits on the nest with her back to the hot sunlight, it makes her glow like an emerald in the needles. At times when the sun would strike either eggs or nestlings, her incubating actually provides shade and insulation from overheating, rather than the usual keeping warm of eggs or offspring. A previous successful nest built in the same general area also had the morning sun issue. Every morning, that Hen would stick tight to the nest until shade returned, holding her wings out over the two nestlings under her, the sun beating down on her own head and back.

At times when the sun would strike either eggs or nestlings, her incubating actually provides shade and insulation from overheating, rather than the usual keeping warm of eggs or offspring. A previous successful nest built in the same general area also had the morning sun issue. Every morning, that Hen would stick tight to the nest until shade returned, holding her wings out over the two nestlings under her, the sun beating down on her own head and back.

(Photo A. Shock. The resolution of the photo suffers from being shot through a window screen.)

By now I’ve managed to get a look at the nest from the upper window when the Hen is away, and discovered you can’t see the interior from the angle that view provides. I was hoping to actually see eggs, but no luck…