What Happened at Beit Bat Ya’anah: part 6

This is the sixth installment of a series. Click on the link at the bottom of the page to continue to the next installment. Or, click here to read from the very beginning. Previously:

This is the sixth installment of a series. Click on the link at the bottom of the page to continue to the next installment. Or, click here to read from the very beginning. Previously:

After the professor’s official and disappointing debunking of the Mystery Object, the staff and students began to move away. Only the undergraduate Eric hadn’t given up on the topic. “What’s a wehériəl sign?” he asked in a tenacious whisper to Zvia, who ignored him as she headed toward the door. “And, say or not say what?” he persevered, following her out the lab door.

The view from under the walls

Zvia Ben-Tor was headed uphill away from the lab as fast as her athletic legs could take her through the moon-blue dark. She was pissed off. The scene in the lab had done it. This late in a tough season it was too easy to lose your cool, so she was ushering her aggravation out into the desert to chill, alone.

Young Eric was still trailing her. The last thing she wanted to do was answer his pesky questions about esoteric Elennui cosmological characters, so Zvia headed towards the latrines, figuring he wouldn’t follow her there. It worked — as soon as she was sure he’d given up, she cut over to the edge of the lower wadi, and made for the ruined springhouse up beyond the edge of camp.

Now well behind her, the dig camp was dark after lights out except for flashlight glow in a couple of the tents and the hazy flicker of someone’s candle at the dining tables. But the compound was still well-lit by the halfmoon light, and Zvia walked around to the other  side of the springhouse to a large flat rock. It was the best place to sit, facing uphill toward the gape of the upper wadi, because dilapidated as they were the thick stone walls blocked out not only the sight but the sounds of camp: late conversation, Lior’s guitar, the Aussies’ laughter. She sat with her back against the pitted limestone, still warm from the setting sun, staring up at the bare cliffs above the wadi, her knees bent toward the sky, her hands curled round her ankles. It was exactly what she wanted – peaceful, solitary and calm.

side of the springhouse to a large flat rock. It was the best place to sit, facing uphill toward the gape of the upper wadi, because dilapidated as they were the thick stone walls blocked out not only the sight but the sounds of camp: late conversation, Lior’s guitar, the Aussies’ laughter. She sat with her back against the pitted limestone, still warm from the setting sun, staring up at the bare cliffs above the wadi, her knees bent toward the sky, her hands curled round her ankles. It was exactly what she wanted – peaceful, solitary and calm.

But the calm didn’t help – Zvi was still pissed off. She was pissed off at Rankle for being a jerk, at Amit Chayes for not being there to mitigate that jerkiness, and even a little at Wayfarer for being so authoritatively and infuriatingly rigorous. And Dario, who’d found the damn character in the first place – where the hell had he been? As usual, nowhere in sight when help was needed, the jackal. How can anyone disappear so efficiently in a close-packed camp in the middle of a treeless desert?

Zvia’s brain kept replaying fragments of dialog. Especially Rankle proclaiming the stamped symbol was “Just a potter’s mark.” Just? Why the hell were they there if not to try to relate the things they hauled out of the dirt to the people who made and used them? Otherwise, at the end of the season, all their hot, hard work would just be square holes in the dirt and rooms full of buckets filled with gray, broken sherds, stripped of meaningful, human context. You might as well leave them buried where they lay.

Otherwise, at the end of the season, all their hot, hard work would just be square holes in the dirt and rooms full of buckets filled with gray, broken sherds, stripped of meaningful, human context. You might as well leave them buried where they lay.

Zvi pulled her heels closer to her hips and continued to stare at the stark cliff faces. The rock looked close, but she knew it was a trick of the clear air and bright moonlight: Shams’s survey put the formation at more than a kilometer away. It was strange, but in a way she could understand Rankle’s view – as an orderly, non-subjective excavator who worships the polished balk and the taut grid he didn’t believe anything but the soil and what it gives up, no matter how meager the yield is. He had no use for texts: words only clouded the clarity of dirt. Zvia had heard the director loud and clear on the subject just last week, when he’d refused to give a site tour to a visiting group from a midwestern Bible college, grumbling about how if they wanted to stagger around Israel brandishing the Old Testament like Baedeker’s guide to the Holy Land, then fine, but did they have to do it here? In the end the other director, Amit Chayes, had showed the group around the site himself, leaving them puzzled as to why they had visited Beit Bat Ya’anah, since he hadn’t used any of the words they knew, like “Israelites” or “Canaanites” or “Edomites,” to describe the people who had lived here: they wanted illustrations for their chapter and verse.

That literalist approach, trying to force matches between archæology and literary texts, didn’t resonate with Zvia, either. But she wondered if what Amit had privately given her the nod to do – to keep an eye open for artifacts that might give a daily life to the mysterious poets whose words she studied – was really any different. Her PhD advisor scathingly referred to it as The Lost Crusade for Elennui Objects. Zvia could understand that viewpoint, too: Elennui Studies people already had a credibility issue with academics outside the field – who studies a language that nobody ever spoke?

Zvia yawned. If she was empathizing with Rankle and Sybar, it was time to get some sleep. She took a deep breath and bent her head back, hoping for a Perseid overhead. A closer movement at the top of the wall caught her eye.

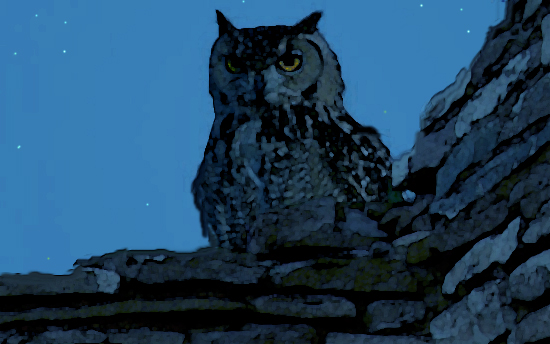

Though the main spring had dried up decades ago, a stingy slick patch still dampened the rocks inside the springhouse walls. It was brown with meagre algae and useless for humans, but it attracted small desert mammals and their hunters. There was a hunter there now, perched right above her: a huge owl, its head-tufts blowing a little in the night breeze, its shape an extension of the jagged wall top. Against the deep sky, the bird’s head swiveled smoothly, and it gave two low hoots.  Amplified by roofless walls, the soft sound carried clearly over Zvia into the open desert below.

Amplified by roofless walls, the soft sound carried clearly over Zvia into the open desert below.

As she watched, the bird dipped its head and stretched a shadowed wing. She wondered how long it had been up there. Forever, she thought sleepily... as long as mice have been coming to the spring for water; how convenient of us humans to build it a wall to hunt from. She tried to dredge up a verse they’d translated in class once, something about an owl’s mournful cries from a desolate wall, but couldn’t retrieve it. There must be no mice at the springhouse tonight – the owl didn’t linger, but launched silently, gliding easily uphill towards the upper wadi.

Following the bird’s flight as she stood to go, Zvia’s quick eye caught another movement, much more distant, almost under the moon-bright cliffs: a ghostly white shirt bobbing among tumbled rocks, headed toward the shadowy mouth of the upper wadi. As she watched the figure disappear under the dark wing of the gap, she realized that what had aggravated her — more than Rankle’s attitude, more than Wayfarer’s shrewd caution, more even than Dario’s vanishing act — was sharp disappointment. Like unprovenanced artefacts, Zvia thought, what good are words, if you don’t know who said them? And she could hardly bear to admit to herself even in the solitude of the blue desert dark how much she had wanted that discrete mark in the clay to be a genuine Elennui wehériəl sign.

[…] To read Part 6 “The View from Under the Walls” click here. […]