[This is a Spot the Bird, although it’s less of a quiz than a photo series. All photos A or E Shock. Click to enlarge.]

Here are some feral date palms, growing wild at a substantial oasis in Death Valley, CA. The date palm is Phoenix dactylifera (“finger-bearing”), but in this case we could call it P. bubifera, “owl-bearing.” There’s an owl in this palm, although you can’t see it. >>

Here are some feral date palms, growing wild at a substantial oasis in Death Valley, CA. The date palm is Phoenix dactylifera (“finger-bearing”), but in this case we could call it P. bubifera, “owl-bearing.” There’s an owl in this palm, although you can’t see it. >>

Owls seem to like roosting in palms. Every birder the world over checks palms for owls. Great horned, Barn, Grass, whatever the local species are — if there are owls and palms together in a habitat or region, they are likely to be acquainted. This is because palms (like pine trees) provide what owls like: concealing, sturdy roosts, and habitat and food source for prey items. An owl perched hidden in palm fronds has a grand view of scurrying, foraging rodents at its feet — imagine regularly finding dinner on your very own kitchen floor… or, to quote Homer: “Mmmm, Floor Pie!” (that’s the epic Homer Simpson, not Homer the epic poet).

dinner on your very own kitchen floor… or, to quote Homer: “Mmmm, Floor Pie!” (that’s the epic Homer Simpson, not Homer the epic poet).

Spot the bird: In the center of this photo, you can see a vague milky blur on the right edge of the darkest dark: the vermiculation, or fine breast barring, of a Great horned owl, Bubo virginianus. >>

It’s nearly invisible because its distinctive yellow eyes aren’t visible; owls roosting in plain sight will often consider themselves concealed by squinting. When even one eye is revealed, the bird  become easier to spot. <<

become easier to spot. <<

I’ve checked a lot of palm trees. I never find owls in them (although I know others who have), but I keep checking. This repeated optimistic searching is known in our family as checking for lard. The term was coined after a cat named the Beefweasel found an unattended pile of chopped fat on a windowsill in our St. Louis apartment, waiting to be put outside for winter-hungry titmice and chickadees. Making good her name, the Beefweasel wolfed down the yummy chunks. Balancing on her hind legs and sniffing hard, she checked that bountiful window-ledge for years hoping for a fatty repeat. Birders are well-known to check for lard, too: there was a nut tree in St. Louis that was searched every winter by local birders on field trips because once in a decade past it had hosted an out-of-range Bohemian waxwing. Among birders, places to check for lard are passed down as oral tradition: I knew about that pecan tree, but the waxwing that made it famous alit there long before my time.

So out of habit  and hope, I was checking these particular palms with my binoculars, searching the deepest shadows for Good Feathery Detail (vermiculation). And there was an owl.

and hope, I was checking these particular palms with my binoculars, searching the deepest shadows for Good Feathery Detail (vermiculation). And there was an owl.

>> The bird never fully unhid; this was the maximum best sighting it allowed.

It was a Great horned owl, tucked in out of the breeze, and not at all worried about us (although we didn’t go very close, being equipped with telephoto lenses and optics — owls are like cats; sometimes you have to respect their invisibility, even if it’s just in their heads).

It’s so delightful to luck into a surprise owl (which, mostly, they are), that we talked about it for the rest of the trip. We referred to this bird as “the Boss in her Office”, because she reminded me of a boss I once had, who lurked invisible at her desk most of the time. Although she was hidden from us as we scurried around busily, it was never a good idea to forget she was there…

It’s so delightful to luck into a surprise owl (which, mostly, they are), that we talked about it for the rest of the trip. We referred to this bird as “the Boss in her Office”, because she reminded me of a boss I once had, who lurked invisible at her desk most of the time. Although she was hidden from us as we scurried around busily, it was never a good idea to forget she was there…

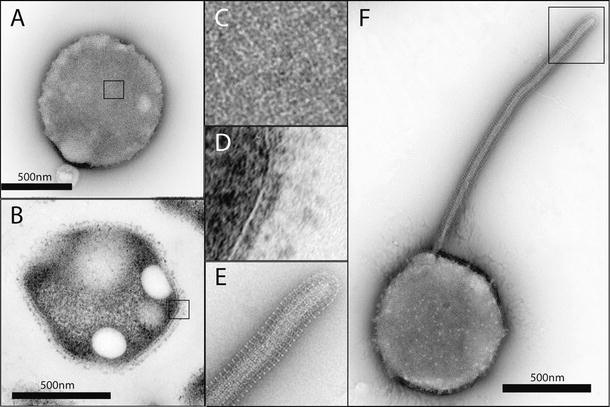

Some readers also know that he’s a geochemist on the faculty of the School of Earth and Space Exploration and the department of Chemistry at Arizona State University. But up until now, no one knew that an organism has been named in his honor. It’s official, and in print — a newly identified archæon discovered living in the very hot water of a geothermal spring at Yellowstone National Park: Thermogladius shockii.

Some readers also know that he’s a geochemist on the faculty of the School of Earth and Space Exploration and the department of Chemistry at Arizona State University. But up until now, no one knew that an organism has been named in his honor. It’s official, and in print — a newly identified archæon discovered living in the very hot water of a geothermal spring at Yellowstone National Park: Thermogladius shockii. a little creaky, that’s New Latin (the “made” Latin of scientific names) for “Hot Sword of Shock”. The transmission electron microscopic photo F to the left shows why — according to M.Osburn and J.Amend, the authors of the article in Archives of Microbiology, some individuals sport “occasional stalk-like protrusions.” (TEM images from Osburn and Amend, 2010)

a little creaky, that’s New Latin (the “made” Latin of scientific names) for “Hot Sword of Shock”. The transmission electron microscopic photo F to the left shows why — according to M.Osburn and J.Amend, the authors of the article in Archives of Microbiology, some individuals sport “occasional stalk-like protrusions.” (TEM images from Osburn and Amend, 2010)