What happened at Beit Bat Ya’anah: Part 16

This is the sixteenth installment of the series. The following links will take you to the last episode before this one, and the very first episode of the series. Also, each post has a link at the bottom to the next episode after it:

This is the sixteenth installment of the series. The following links will take you to the last episode before this one, and the very first episode of the series. Also, each post has a link at the bottom to the next episode after it:

Read Part 15 ……………………………….For new readers: Read Part 1

Previously:

In her continuing attempts to learn about Beit Bat Ya’anah, Professor Wayfarer is offered after dinner refreshments by the camp manager Moshe, while he tells her a glorified tale about a part of the site’s history from the fairly recent past: the story of the Greenboim Brothers and their ostrich farm. An unwelcome (to Moshe) interruption by Wilson Rankle redirects the camp manager to telling a less idealized version of the tale, to which the Professor listens closely, and learns unexpected things.

Moshe’s tale part 2: smuggling eggs

A hot breeze had kicked up while Moshe was talking, swirling grit against Professor Wayfarer’s ankles. The string of little lights swung overhead, making shadows jump on the vinyl tablecloth. A stiff gust scoured one of the Bamba snacks out of the bowl and blew it across the table into the dirt. Wayfarer watched the starchy puff hop rodent-like across the compound. Its unnatural beige coloration caught the moonlight, making it  easily visible until it lodged in a cage-like spurge at the far side of the open area. “It’s the sand rat’s lucky day,” she said.

easily visible until it lodged in a cage-like spurge at the far side of the open area. “It’s the sand rat’s lucky day,” she said.

But Moshe was focused on ostriches. “What the Greenboim brothers did wasn’t stealing, exactly,” he said again.

“No?” she asked.

“No.” The camp manager shook his head. “More mits, Professor Einer?”

“No!” barked Wayfarer, putting her hand over her plastic cup. “Thank you,” she added belatedly.

“Not stealing. It was….” Moshe circled a finger in the air, to conjure the word he wanted. “The opposite. Not taking something illegally, bringing something illegally.”

It puzzled the professor, but only for a moment. “Smuggling,” she suggested. She was intrigued by his opposition of stealing and smuggling, antonyms she herself never would have paired. But from a certain perspective – if you ignored the obvious axis of legality – it was logical. It reminded her of debating with Avsa Szeringka: Wayfarer admired the mental agility, while disagreeing with the premise.

“Yes! Smuggling.” Moshe slapped the table. “That’s not like stealing – who did it hurt? And it wasn’t the birds: how could you smuggle a big animal like an ostrich into or out of anywhere? No, remember I told you – the older brother Avidor had once worked in an ostrich farm in South Africa. He still had friends there. They told him there were rules about ostriches leaving the country. The market for meat, feathers, and leather was good – the South Africans didn’t want competition, so no birds could be exported. But eggs were different. No one cared about eggs – how could chicks in the egg survive the flight? you would arrive only with a big souvenir. So Avidor got eighteen eggs, a lucky number – and they flew back to Israel with them.”

“That’s a long flight for viable eggs they hoped to hatch. They chartered a plane?”

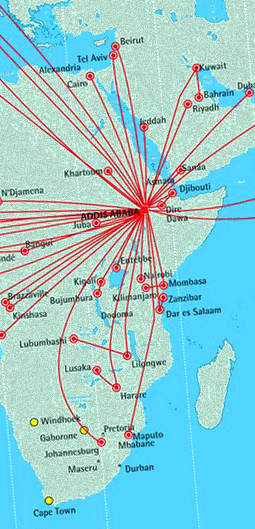

Moshe’s thick eyebrows bent upward. “You think they were made of money? No, El Al, tourist class, regular Johannesburg-Addis Ababa-Tel Aviv run. They carried the eggs in kitbegs they took on board.” The camp manager sat back, enjoying the leisurely rhythm of his tale.

The professor repressed a sigh. She wondered if it was the story making her impatient, or the unaccustomed influx of after-dinner sugar in the mits. If only the Aussies had managed to bring her wine from Eilat — a nice red was much more conducive than this sweet juice to long after-dinner tale-spinning. Shams said they’d bought some, but somehow – unlike the Hawaii brand shampoo – the bottle hadn’t survived the late-night drive back to the site. Clean, tropical-scented hair was hardly compensation; it was understandable if she sounded a bit sharp. “You’re saying that the Greenboims smuggled a dozen and a half ostrich eggs past El Al security in their carry-on bags?”

Moshe shrugged. “No, I told you – that part was all legal, nothing done be’shushu. No one cared about eggs back then. El Al security was looking for hijackers’ bombs, not eggs. Eggs are not a problem; eggs don’t blow up.”

“Then where did the smuggling come in?”

“That’s what I’m telling you! It was a matter of timing. Eggs about to hatch didn’t need extra warmth to survive the flight, but if they hatched, disaster! – the Greenboims had no permit for bringing live animals.” Moshe shrugged. “Avidor did the best he could, but he picked eggs closer to hatching than he thought, and the kitbegs were warm.”

“So the eggs did blow up…”

Moshe nodded. “The first thing the brothers knew of it was over Khartoum – little peep peep noises coming out of the bags at their feet. After a couple of hours there were six, seven, eight small ostriches poking and pecking, then nine, ten, eleven, fifteen baby ostriches by the time they landed. Even the pilot came back to see the sight. That’s what the Greenboims smuggled into Israel – fifteen baby ostriches. Plus three eggs. In bags. Like I said, the eggs were no problem, but with no permit the baby chicks were a different story.”

“So what did they do?”

“They did nothing; it was the pilot who helped. He told the brothers to close their kitbegs tight and walk through customs with him. The pilot was a big important man and everyone knew him, so it worked. With him  Danny and Avidor walked right through no problem, they were in!” Moshe made a triumphant sliding gesture with his hand to cap the tale. “Thanks to the Greenboims, there were ostriches in Israel once more!”

Danny and Avidor walked right through no problem, they were in!” Moshe made a triumphant sliding gesture with his hand to cap the tale. “Thanks to the Greenboims, there were ostriches in Israel once more!”

The professor took off her glasses, rubbed her eyes, and considered her response. Moshe was looking at her expectantly. She’d heard more than one colleague give a paper like this: a premise so enthusiastically presented you almost wished to overlook its improbability. It made a good story, but… She replaced her glasses, and was about to inquire about an obvious weak point when there was a nearby pop, then a more distant ratcheting grind. The lights dimmed and went out, leaving the whole camp dark except for moonlight. A combined cheering and groan issued from the lab building below.

Nine o’clock already? Moshe’s tale had taken even longer than she thought. Wayfarer held her watch near the flashlight; no — its hands showed 8:17, well short of usual lights-out.

Across the table the camp manager swore. “I’m sorry, Professor Einer, I have to take the flashlight now to look at this ma’afan generator. Please sit and enjoy the mits. Layla tov.” He nodded at her and moved off towards the afflicted equipment muttering irritably, transformed abruptly by malfunction from gracious host into testy camp manager once more.

* * *

Without Moshe’s flashlight or the camp lights, the moonlight shone bright enough for Wayfarer to see the escaped Bamba snack jump in the branches of the spurge as the air stirred it. Without the generator noise in the background, she noticed the breeze whistling in the tarp’s guylines, the gentle flap of the canvas, a jackal yipping at a distance. But what passed for desert darkness and quiet were brief. Moshe had barely disappeared when the staff who’d been working in the lab came trickling up the hill in a loose, chatty herd like goats. Lior, young Eric, Rory, and Zvia came first, laughing at something among themselves as Shams and the other Aussies split from the group and headed towards the springhouse. Then came Rankle and Chayes bringing up the rear like the shephards, discussing the day’s stratigraphic crux in low voices, their path lit by Rankle’s flashlight.

Zvia plunked herself down at the end of the table. Wayfarer saw her notice the snack tray and mits, along with Moshe’s retreating back. “Enjoying a chat with Moshe, Professor?” Zvia smiled. She helped herself to a handful of Bamba. “Would it have anything to do with ostriches?”

“Indeed; we talked Greenboim ostriches until the generator gave up the ghost.”

Rankle set his flashlight on the table, aimed at the plastic pitcher of mits, which threw off a dim, lemon-flavored glow, just sufficient to see who was who. “He’s got a fixation on those two scoundrels and their damn birds,” he tutted.

“I would say it differently.” Chayes’s deep voice was kinder. “To Moshe the brothers are heroes: independent problem solvers working on the edge of the system to make things better. He sees himself in them – rules exist to be creatively interpreted, as long as no one’s harmed.”

Rory asked, “Which version of the story did he tell you, professor?”

Wayfarer felt professional satisfaction – any good traditional tale had more than one recension. “Version?” she prompted.

Amit smiled, “Did the eggs hatch on the plane? Did the stewardesses help sneak the eggs through customs?”

“Well, there was pipping and peeping. No stewardesses, though. The ranking pilot came to the rescue.”

“He told me the stewardess version,” grinned Rory. “The girls put the chicks in their… uh… uniforms.”

Zvia snorted. “That wasn’t the version I heard. He told me a smart ‘lady doctor’ who happened to be seated in the same row helped hide them in her medical bag.”

Chayes lifted a shoulder. “It may have happened that way. However they did it, the Greenboims brought ostriches back to Israel. That’s what’s important to Moshe.”

“Too bad the whole thing ended so badly,” Rankle said.

“How so?”

“It was all due to shoddy research.” Rankle sniffed, as if he could smell the odor of sloppy fact-finding. “They hadn’t consulted an expert, and they got the wrong birds: Nature Reserves Authority biologists objected to the South African sub-species, and refused to introduce it into the wild here. Worse, this strain of ostriches turned out to be stupid and vicious – Danny lost an eye to one. No one wanted the birds after that. It was all over.”

“They couldn’t sell the ostriches for meat?” Wayfarer asked.

Chayes shook his head. “Avidor wanted to, but ostrich isn’t kosher, and no exporter was interested in such a small quantity. Anyway Danny refused to kill the birds –  despite everything he felt responsibility since they’d brought them here. Besides neither brother wanted to give up. But they needed money to keep on, so they tried to change directions with the farm. They added some pens with a toothless old hyena, an ibex, a leopard cub, some goats and bee-hives – for the land of milk and honey – and the Beit Bat Ya’anah Ostrich Farm became a small zoo of biblical animals. They even sold postcards and cheap souvenirs to the tourists.”

despite everything he felt responsibility since they’d brought them here. Besides neither brother wanted to give up. But they needed money to keep on, so they tried to change directions with the farm. They added some pens with a toothless old hyena, an ibex, a leopard cub, some goats and bee-hives – for the land of milk and honey – and the Beit Bat Ya’anah Ostrich Farm became a small zoo of biblical animals. They even sold postcards and cheap souvenirs to the tourists.”

“That failed as well,” Rankle chuckled, “in a kind of dire ornithological twist: the ostrich as albatross. Sounds like a subtitle for one of your colleagues’ scholarly efforts, Einer. Is there an equivalent to karma in your abstruse language?”

It was unclear to Wayfarer why the man found the brothers’ failure funny, and she didn’t appreciate the deprecating tone of his question. “Yes, Bill, in fact the Elennui language expresses several related concepts,” she replied blandly, repressing his incivility with academic detail. “The closest might be huwúm. It’s usually translated as ‘inescapable resolution.’ Especially appropriate since it also has an ornithological connection, although it’s ‘owl’ and not ‘albatross,’ so you’ll have to abandon your Coleridge metaphor.”

Chayes interrupted this chilly exchange placidly. “Well, things didn’t go bad for the brothers right away. The bees were very productive at first, and honey sales kept the ‘zoo’ going for a little while. But the leopard was expensive to feed, and the track was too long and rough – you’ve ridden it, it’s the same road we use now. Not enough tourists came. Then the bees left the hives – no one knew why, or where they went. Without the honey income, the brothers ran out of money before their second summer. That spring they abandoned the site just like the bees. Danny opened the animals’ cages wide before they drove away. The Bedouin claim they still see a leopard in the rocks up the wadi from time to time.”

the brothers ran out of money before their second summer. That spring they abandoned the site just like the bees. Danny opened the animals’ cages wide before they drove away. The Bedouin claim they still see a leopard in the rocks up the wadi from time to time.”

“Hence I ask you, who would go up there in the dark,” said Rankle, “except an idiot?” After this assertion he found it necessary to smooth his comb-over.

Next to her on the bench, Wayfarer felt Zvia shift uneasily, and glance at Rory.

Rankle picked up his flashlight, leaving the group around the table in darkness. “Well, I don’t think we’ll be achieving illumination any time tonight,” he said. “I’m packing it in.”

Chayes stood too. “I’m going see if Moshe needs any help. Layla tov.”

“ani ba itkha,” said Lior, following him. As he left, he looked back at Rory and Zvia, and said, “I won’t be long. lehitra’ot.”

No one else moved, or switched on a flashlight. Patient and silent in the dark, Wayfarer waited, like a lion at a watering hole. She felt there was more to be learned.

“It’s just a legend, right?” young Eric asked when the directors were out of earshot. “The Greenboim’s leopard? I mean, it couldn’t still be alive after all these years, could it?”

“I don’t know how long leopards live,” Zvia replied tartly. “Rankle’s just being…”

“…himself,” Rory summed up. “Talk about having a fixation. He’s worked up about the wrong thing, as usual. He’d pop a vein if he knew what the Aussies and Mikka are up to behind the springhouse right now.”

Eric giggled, and Zvia shushed them both. “I’ll clean this up, professor, and lock up, if you’re through.” She gathered up the remains of Moshe’s hospitality, pouring the loose Bamba snacks from the bowl back into the bag and taking up the tray. “Goodnight. See you in the morning.” Her small hands full, Zvia marched efficiently to the mess tent.

With one big hand Rory snagged the open bag of Bamba snacks as she passed, then together with Eric he headed uphill; toward the springhouse, Wayfarer assumed. Whether Zvia followed them or not, the professor didn’t notice: none of this was a revelation she cared about in the least. What the staff got up to after hours wasn’t her concern. But did they really think that the distinctive smoke – which frequently reached her tent, wafted downhill on the cooling night air – was a secret?

She doubted it. More likely they were simply willing to risk it: a few minutes of sociable, clandestine relaxation after the grind of wearisome digging and field analysis would be considered well worth whatever unpleasantness Rankle dished out. Wayfarer couldn’t blame them: the man would drive anyone to furtiveness.

Reflecting on everything she’d heard, the professor surprised herself by feeling a pang of sympathy for the Greenboims. Returning Old Testament fauna to Israel must have seemed sufficiently worthwhile to face the risks. But in the attempt the brothers lost their investment, Danny lost an eye, and there still wasn’t a viable wild population of ostriches in the land. To be dismissed as nothing but “scoundrels” by Wilson Rankle on account of shoddy research seemed too harsh. Wayfarer valued solid research highly, but the price the brothers paid for their good intentions had been severe.

Call it what you will: karma, nemesis, manīyah, Schicksal, huwúm, or inevitability, the concept of moral cause and effect had been near the heart of human stories for millennia. Open a newspaper, read a novel or a poem from any people or culture, and you’d see the same story written a thousand ways. The obscure literature she studied was full of such plots in every permutation, some full of regret and retribution, others subversively rejoicing in the victory of right over law. And, as she told her students, only the finest line lay between the comic triumph of the unrepentant  scoundrel and the tragedy of the misguided hero.

scoundrel and the tragedy of the misguided hero.

Sitting alone in the dark, Wayfarer was no longer thinking especially of the Greenboims, or Moshe’s flexible versions of the truth, or the youthful crew’s indiscretions, but of Szeringka’s elusive protégé Dario and his illicit nocturnal forays into the upper wadi.

She looked up the ridge past the springhouse toward the moon-washed faces of the cliffs, to where they were marred by the dark gash of the wadi’s mouth. It was an entrance, but also an exit: a shadowed cleft that held secrets, but also disgorged them.

The professor decided that she needed to know more about the wadi.