What Happened at Beit Bat Ya’anah: Part 17

This is the latest installment of the series. The following links will take you to the last episode before this one, and the very first episode of the series. Also, each post has a link at the bottom to the next episode after it:

This is the latest installment of the series. The following links will take you to the last episode before this one, and the very first episode of the series. Also, each post has a link at the bottom to the next episode after it:

Read Part 16 ……………………………….For new readers: Read Part 1

Previously:

The excavation season at Beit Bat Ya’anah is in its last two weeks, and Zvia BenTor is catching up on her personal letter-writing while she can. Before we look over her shoulder, let’s re-open earlier correspondence. First, the ambiguous letter that set things in motion, sent by Avsa Szeringka, grande dame of Elennui Studies, to her American counterpart Einer Wayfarer, meant to entice her to the unenchanting archeological dig deep in the Negev Desert. Then, three other messages: one from Wayfarer to Szeringka, short and wry like its author, intended to stir the pot; and a pair of letters – one rebellious and insolent, the other imperious and fierce – two sides of a fiery exchange between Dario and his adviser and mentor Szeringka, the contents of which we can only guess.

Correspondence: letters home

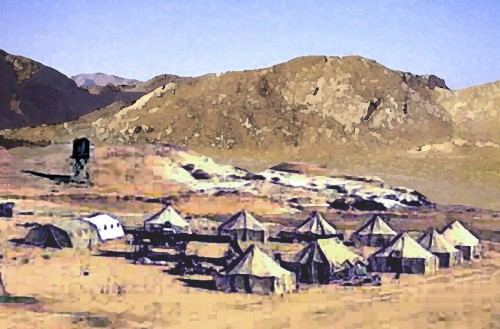

It was after lunch in the camp on the ridge below the wadi, the part of the day when it was too hot to work in the lab — too hot even to nap. Today it was also too noisy: since early morning F-16 Falcons had been shrieking northward up the valley in pairs every few minutes, wingtips slicing the wh ite sky. Kept by heat and noise from holing up in the tents for sleep, various Beit Bat Ya’anah staff lounged in the sharp-edged shade of the dining tarp, trying to minimize contact with the plastic table-cloths and each other: everyone was spaced unsociably, as far apart as the small number of tables and the concentrated shade allowed. The Australians idled in a teasing, loose clump; at the next table Shams was trying to coax his semi-broken Walkman to play an Icehouse cassette. Moshe, muttering and sweating, was re-attaching something to the tarp frame with heat-molten duct tape. And a few distracted-looking BGU students were either huddled around a transistor radio, or listening to Lior strum Wimoweh on his guitar as IAF Kfir jets — Lioncubs — roared overhead, shaking the rocky ground of the ridge underfoot.

ite sky. Kept by heat and noise from holing up in the tents for sleep, various Beit Bat Ya’anah staff lounged in the sharp-edged shade of the dining tarp, trying to minimize contact with the plastic table-cloths and each other: everyone was spaced unsociably, as far apart as the small number of tables and the concentrated shade allowed. The Australians idled in a teasing, loose clump; at the next table Shams was trying to coax his semi-broken Walkman to play an Icehouse cassette. Moshe, muttering and sweating, was re-attaching something to the tarp frame with heat-molten duct tape. And a few distracted-looking BGU students were either huddled around a transistor radio, or listening to Lior strum Wimoweh on his guitar as IAF Kfir jets — Lioncubs — roared overhead, shaking the rocky ground of the ridge underfoot.

At the edge of the group sat Zvia Ben-Tor ignoring it all, barefoot, with a sun-faded rainbow scarf wound around her head, its knotted fringe tickling her neck in the hot wind. She kept brushing at it unconsciously, as if shooing a bug. On the table lay a stack of letters weighted with a battered, handy cobble so she didn’t have to chase them across the compound a second time while the Aussies twitted her about “Air Mail.” Except for the one to her uncle in Tel Aviv, the letters were in fact air mail, addressed to the States and decorated with blue and white do’ar avir stickers. Zvia always picked up sheets of the gummed stickers at the Be’er Sheva post office before going into the field, since their winged image of a swift deer personalized her correspondence: tsvia was a Hebrew word for doe. Though there were several envelopes under the cobble they made only a thin stack — her lilac airmail paper was so light that she could get several sheets into each envelope without extra postage. This was useful, because on paper Zvia was more talkative than she was in person.

compound a second time while the Aussies twitted her about “Air Mail.” Except for the one to her uncle in Tel Aviv, the letters were in fact air mail, addressed to the States and decorated with blue and white do’ar avir stickers. Zvia always picked up sheets of the gummed stickers at the Be’er Sheva post office before going into the field, since their winged image of a swift deer personalized her correspondence: tsvia was a Hebrew word for doe. Though there were several envelopes under the cobble they made only a thin stack — her lilac airmail paper was so light that she could get several sheets into each envelope without extra postage. This was useful, because on paper Zvia was more talkative than she was in person.

By the middle of the afternoon, she’d finished writing to her parents, her little brother, her older sister who shared her Princeton apartment, and her aunt Laura. Now she was writing to a pal from undergrad days who was currently a grad student in MacCormack U’s Elennui Studies program. Though Dugan would tease her for gossiping, Zvia knew her news would fall on especially interested ears: Einer Wayfarer was his advisor. She situated the page so that none of the nearby Aussies could snoop, and dished:

“… very disappointing that after coming all this way she wouldn’t allow our mysterious character to be the wehériəl sign – Anyway that was more than a week ago and she’s still here. No one knows why. I overheard her say something to Rankle about staying. There was no asking just telling. Although it’s not like she’s just hanging around. She’s everywhere – now I get why you call her ‘The Eye’, she doesn’t miss a thing, does she? – helping out on the hill and in the lab, which is actually useful since the IDF is reinforcing its ranks by thinning ours. Now if only we can get young Eric to shut up about Indiana Jones — he sounds like such a jerk going on about that movie, when the sabras are worried about being called into combat…”

Out of the corner of one eye, she was aware of someone approaching. She stopped writing, but it was just Shams with his natty hat and a question in his eye. “Need some laundry soap, Shams?” she anticipated. It was a site mystery: since he usually wielded a transit instead of a trowel like the rest of them, Shams’s clothes never got dirty — yet he was always washing shirts with other people’s powder. “There’s a half-empty box of Maxima under the bunk in my tent. Just leave a little for me, okay?” Shams veered away towards the tents with a tip of his stingy-brim and a thumbs-up. Zvia re-read her last words, added some more underlining, and continued:

“Anyway the Eye seems to be eyeing Szeringka’s pride and joy – Dario Some-Last-Name-I-Can’t-Spell from her Institute — no, not eyeing that way, ecch! — I just mean asking questions. It doesn’t seem to be working — he’s made himself pretty scarce since she got here. He’s supposed to be a hotshot Elennuist, you’d think he’d want to schmooze the eminence grise. But with all the mummy-bead bracelets, slinky physique, and eurotrash accent he doesn’t exactly ooze academic credibility (although some of my co-workers don’t seem to object to whatever it is he does ooze). So, is the Eye just scouting Szeringka’s bench or what? Or maybe it’s all in my imagination — she’s always asking everyone about everything…”

Here Zvia looked up in time to witness a small scene unfolding in the hot sun, which illustrated her point perfectly, so she passed it on to Dugan as it happened:

“In fact someone should warn Shams right now because there goes The Eye after him marching across camp towards the Trough toting her laundry bag and sporting a dorky bucket hat and stumpy beige shoes – I don’t suppose you’ve ever seen her in field togs? Although Moshe (He of the Sandals-with-Socks and tembel hat)

seems to appreciate the look – in fact now there he goes after her trailing duct tape and concern to see if she needs anything… ever since she asked him about the Greenboim’s ostrich farm he… oh, that’s right – you don’t like to gossip so you won’t want to hear about our social intricacies. Anyway things relaxed around here after Amit got back so we’re not solely under Wee Willie’s thumb and the food’s been soooo much better since they demoted Mikke the “cook” back to photographer (did I tell you about the hyrax skull incident?) because Dario flings falafel way better than he ever did dirt.… Oh, hell!”

This last startled exclamation was aloud. With no warning except a slight scent of cedar mixed with frying oil and dish soap, along with something distinctly more volatile, someone had come up behind her. It was Dario, the last person she’d expect to see at this time of day. He sank onto the bench, sidling over until his hip pressed against hers. He laid one hand on the cobble weighing down her letters and asked, “May I have this?”

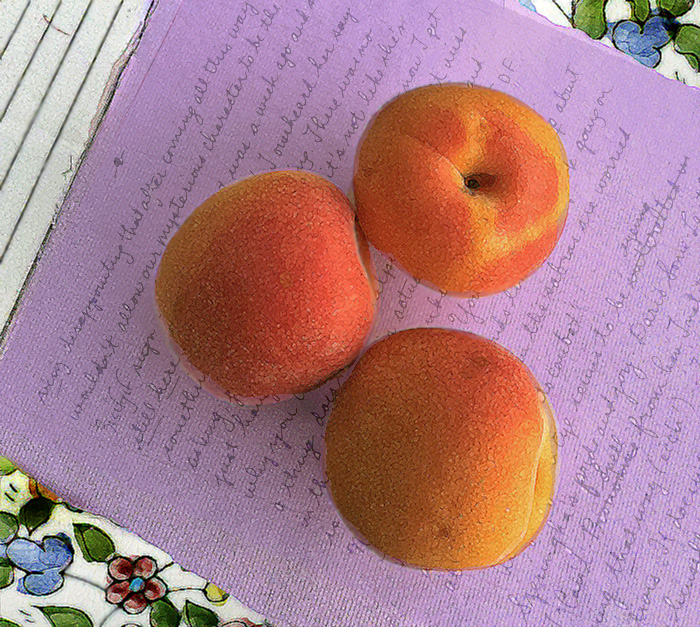

Folding the page over so he couldn’t see what she’d been writing, Zvia shifted away and opened her mouth. A desert full of rocks, and he had to have that one? But before she could say no Dario set three plump apricots on the table in front of her. “Use these instead.” His face was inches from hers, his chin as round and dimpled as the fruit.

The sun-warmed fruit glowed golden against the lilac envelopes, emitting a soft floral scent. “mish-mish! — where did you get them?” Zvia exclaimed. It had been weeks since there had been any fruit in camp but tinned peaches.

“The last of the season, from Kibbutz Shizafon. I pursuaded Lior to bring a box from home. His brother works in the groves. All three, for that ugly stone.”

Without doubt it was an excellent trade, but she wasn’t going to let him know it. “So why do you want it?”

“It looks just right. And because Moshe won’t lend me another hammer.”

Better not ask, Zvia decided, and instead sealed the deal. “For three apricots, the rock’s yours,” she gestured towards it with her chin, and picked up her pen. “But you overpaid. I would have settled for two.”

Dario smiled, but didn’t take the cobble. Zvia said, “Look, I’m trying to finish a letter, do you mind?”

“I don’t mind.” He eyed the stack of mail, and didn’t budge. “You wrote to all of those people?”

“Just letters home,” she said, “to my family, mostly. It’s not as good as a phone call, but better than nothing. No asimonim, anyway.” She looked around at the desert surrounding the camp and added, “Not to mention no pay-phone to put them in.”

“And do they write back?”

“Of course, except my butthead brother.” She tried again. “Aren’t you going to take your rock? Away?”

Dario leaned across her, reaching for the cobble. Zvia felt his warm ribs press against her briefly before he leaned away again. It occurred to her how few personal details she knew about him, even after working together all season. That was odd, for her – usually everything worth knowing about everyone on site was filed in her head long before this. For instance, where was Dario actually from? Current camp rumor had recently migrated from Yugoslavia to Italy, but Zvia couldn’t think why she’d never asked him directly. “Where do you call home, Dario?”

“Here,” he said, after considering. “I live here…”

“At Two-Bit-Yod?” Zvia laughed. “Well we all do, at the moment – us and the wasps and the centipedes. No, I mean where does your family live, where do you go between terms?”

He took one of her work-roughened hands in his even rougher one and turned it upward. “I know what you mean.” He pulled an ornate fountain pen from his shirt pocket, and began to write. The sticky pen-point dragged across Zvi’s palm, tickling, line after line, its i nk giving off an exotic, coniferous odor. “I stay at the Institute,” Dario said, still writing. “Szeringka’s Institute. Near Oxford.”

nk giving off an exotic, coniferous odor. “I stay at the Institute,” Dario said, still writing. “Szeringka’s Institute. Near Oxford.”

“I know where the Institute is,” Zvia said. Everyone in their field knew about the Institute, and the rumors.

He looked at her, lower lids slightly raised, and after a pause said, “Then you know where I live.”

Zvia didn’t pursue it – if he wanted to shelter behind an aura of sultry euro-mystery, fine: it was probably more interesting than whatever the truth was. She took her hand back when he didn’t release it, and offered, “Well, if you ever want to write on actual paper, I’ve got plenty of stationary.” She turned away to finish her own letter.

“Thank you, cara, I already wrote a letter home.” Dario replied, standing. “But I didn’t like the reply.”

After a moment, Zvia looked up. “What?” she asked. But he was already out of earshot, and almost out of sight. Typical, she thought — he was either too close up, or too far away. And he’d left the damn rock. “Hey, thanks for the mish-meshim,” she called after him anyway. Only then did she unfold her palm to see what he’d written there in fragrant blue ink.