… or, saving shots by going artsy…

Not all photos are created equal, especially if you’re an amateur photog like me who asks my competent but limited point-and-shoot digital camera to do things it wasn’t meant to do, like capture images of cryptic birds high in trees with too many leaves against the light on an overcast day through a fogged-up scope (see previous potoo posts) in a hurry.

And, some birds don’t have the courtesy to pose standing still six feet away in the open in the light for an hour while some fudge-fingered camera-camel like me tries to get a shot  off before they get on with their lives finding scarce food, competing for mates, and evading swift-grasping predators.

off before they get on with their lives finding scarce food, competing for mates, and evading swift-grasping predators.

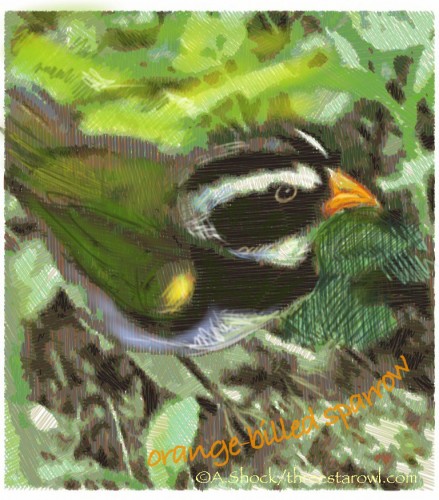

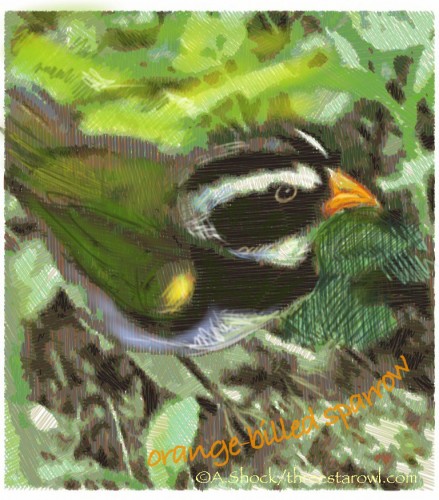

<< app-altered digital image of an Orange-billed sparrow (photo and alteration A.Shock). Orange-billed sparrows (Arremon aurantiirostris) are striking but rather skulking sparrows inhabiting moist woodlands from southern Mexico to northern South America, not terribly uncommon or hard to see but tough to photo. A bold black-and-white head pattern, a lovely olive back, golden epaulette and neon orange bill make them distinctive as they hop about the shadowy forest floor in small flocks.

So, not all photos are created equal. I have lots of “unequal” photos from trips, including this last Costa Rica visit. Despite expert bird-finding leadership turning up an unexpected number of fabulous sightings by eye, dim and moisty cloud forests, furtive species (and you know who you are, Silvery-fronted tapaculo), and awkwardly-wielded umbrellas all cut down the number of useful pix to post here. Some species (Quetzales for instance) I missed entirely; others, such as the Orange-billed sparrow, I only got blurry, distant, or otherwise unusable images of. Photoshop (even the archaic version I’m still using) and iPhoto are both hugely helpful, and have saved many a photo for publication. But now I have new tools — cribs, if you insist — to produce internet-ready images for this space from unpromising jpegs. (Let me add FYI, in case the reader hasn’t read the fine print at threestarowl.com, that this is not a commercial blog, and I receive no compensation whatever for testing, using, praising, demonstrating, criticizing, or even just mentioning any product, service, or company).

A recent fairly unintentional acquisition of an iPad has given me tools that are similar to Adobe Illustrator and its kin, but are even more user-friendly: SketchmeeHD, SketchbookPro, and TypeDrawing. Here is the step-by-step process by which I used these apps to turn an unusable jpeg image into a lively illustration for this post:

<< Far left, original unaltered shot of Orange-billed sparrow: subject too small to see. Near left, cropped to zoom, the colorful plumage and bill are captured, but the lack of focus due to movement and low light is painfully evident. Verdict: not publishable in either form.

So, I sicced the iPad app “SketchmeeHD” on the cropped version of the original jpeg. This cool application renders an original image into an algorhythmically-generated series of layered colors and strokes, as if it were drawn from colored pencil. It’s easy and quick for the operator (and entertaining, as the image is produced in stages as if being drawn before your eyes by an invisible hand), and nearly but not entirely id iot-proof: there are choices to make, such as opacity, density and substrait.

iot-proof: there are choices to make, such as opacity, density and substrait.

<< These were the results. It looks adequate artistically (click to enlarge to see pencil-marks), but it’s a bit mechanical looking, sterile. Annoyingly, but not surprisingly, the lack of focus was faithfully transmitted from the source image, and not magically cured. Worse, from a birder’s point of view — and probably a bird’s, too — all the distinctive colors have been muted to the point of dullness. Where’s the olive back? The golden epaulette? The eye? The eponymous orange bill, for crying out loud? These are Important Characteristics, Field Marks, and not to be done without, even if this is not a field guide. Especially if they’re only eradicated by the mere randomness of digital manipulation. Verdict: insufficient improvement, unpublishable.

But, I have recourse. At this point, I opened the SketchmeeHD-altered jpeg with SketchbookPro, another iPad app. By “drawing” with my finger on the iPad’s interactive screen and selecting parameters such as color, point type, width and opacity, I was able to  restore liveliness and color to the automatically-generated “pencil strokes” by adding my own hand-controlled digital marks which, even through the electronic medium, supply the human touch, visible in the finished version.

restore liveliness and color to the automatically-generated “pencil strokes” by adding my own hand-controlled digital marks which, even through the electronic medium, supply the human touch, visible in the finished version.

<< The final step was to use the app TypeDrawing to add the bird name caption. This app allows you to enter type in a color, size, font of choice and place it in your image; the path of your finger on the screen determines the line and position of the text.

Verdict: Publishable illustration of Orange-billed sparrow.

The photos I use on this site, whether taken by me or others, are minimally altered for clear viewing, and never “faked” (except for fictional effect and with full disclosure). Altering photos to prove the identification or occurrence of a bird in a particular place or time is obviously just wrong (for instance, my Maroon-chested dove shots are unaltered except for cropping to enlarge the bird, and the video is entirely unaltered). Images in this blog, for the most part, are intended to tell a story, please the reader (and myself), and provide visual  interest besides text. Most are digital photos. Some, like the joyfully garish Resplendent Quetzal image are produced entirely from scratch from a blank “page” with SketchbookPro, driven by the touch-interaction of the iPad screen with my nail-bitten finger.

interest besides text. Most are digital photos. Some, like the joyfully garish Resplendent Quetzal image are produced entirely from scratch from a blank “page” with SketchbookPro, driven by the touch-interaction of the iPad screen with my nail-bitten finger.

By contrast, an image like the Orange-billed sparrow above is heavily altered — in fact, it’s published only because of my ability to alter it. I do “real drawings” too with pencil, colored pencil, and water color, and to me the apps are not going to replace those techniques — they’re just a different medium than those more traditional paper-born tools, with different limitations and different advantages. Maybe you’re comfortable with this process, maybe not. Possibly, by posting the techniques behind the results, I’ve made readers think less of a finished product like the Orange-billed sparrow image, as not being real “art”, or requiring less skill than a “real drawing”. That’s up to everyone to decide for themselves. Personally, I consider it illustration, and I’m thrilled to be able to present a pleasing visual image of a lovely creature that otherwise would have remained uselessly stuck in the craw of my computer.

which was fairly low in a crooked Aleppo pine in our backyard, right over a gravel path through the side of the garden. There was a big wind storm, and chilly late-winter temperatures.

which was fairly low in a crooked Aleppo pine in our backyard, right over a gravel path through the side of the garden. There was a big wind storm, and chilly late-winter temperatures.