Is this the offending foam?

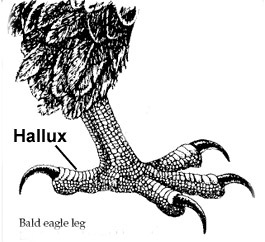

On last weekend’s trip to the Oregon coast, E and I noticed the beaches were festooned with unsupported sea-foam, churned up by the waves . This might have been the slimy foam that’s currently causing major problems for sea birds along the Oregon coast. The foam, a result of an off-shore algal bloom, coats the bird’s plumage as they dive or float in affected seawater. This destroys the water-proofing loft of down feathers, the warmth-holding space under the countour plumage which keeps the birds warm in cold water.

. This might have been the slimy foam that’s currently causing major problems for sea birds along the Oregon coast. The foam, a result of an off-shore algal bloom, coats the bird’s plumage as they dive or float in affected seawater. This destroys the water-proofing loft of down feathers, the warmth-holding space under the countour plumage which keeps the birds warm in cold water.

(Above: Foam-coated beach, Fort Stevens State Park; photo E. Shock)

Hundreds of hypothermal seabirds, including loons, murres, grebes, and puffins, are washing up on shore on along the northern beaches of Oregon. Extraordinary efforts are being made to save these animals at wildlife rescue centers both in Oregon and California. The Coast Guard is helping evac the feathered patients from Oregon to a high-tech rescue center in California which is designed to help victims of oil-spills — read about it here and here.

Extraordinary efforts are being made to save these animals at wildlife rescue centers both in Oregon and California. The Coast Guard is helping evac the feathered patients from Oregon to a high-tech rescue center in California which is designed to help victims of oil-spills — read about it here and here.

(Right, unsupported sea foam, photo E.Shock)

We didn’t encounter any of the suffering birds, fortunately, but we did see a number of loons, grebes, and sea-going ducks like scoters cruising the near-shore waves on beaches covered with blowing clots and rolls of sticky foam.

(Left: Red-throated loon, photo E.Shock. Note that there’s a small wavelet behind the bird’s beak that’s making the bill look thicker than it actually is.)

down-wind on a gale at the South Jetty at Fort Stevens State Park.

down-wind on a gale at the South Jetty at Fort Stevens State Park.