Late Night Arthropod: Vaejovis aglow

Scorpions are not a thing at our house. We don’t see them frequently, and as previously posted, they’re more likely to be encountered outside as victims of the swimming pool than inside the house. But last night E liberated one from the front bathroom, and temporarily incarcerated it in a pint glass.

In the morning, I wanted to watch it glow. Here’s a picture of it viewed under a UV light, with the glass’s Duralex logo for scale. It’s another “striper”: Vaejovis spinigera, a stripe-tailed scorpion, our most common species.

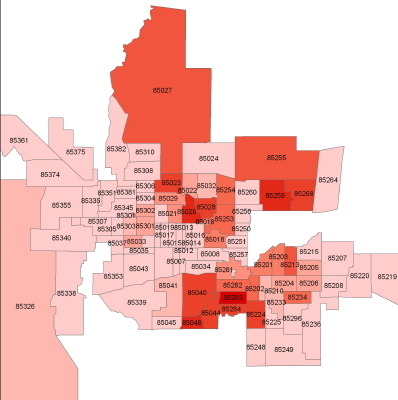

There are places in the Greater Phoenix famous for their scorpionicity. So much so, that you can find maps of the frequency of scorpion stings on the internet, for the benefit of people new to the area who might want the info while searching for a house to buy. (We looked at a map of Superfund sites, but everyone has to prioritize their own worries). Such a map is to the right: the darkest areas show the areas with the most stings reported, so it’s more likely to reflect factors such as human population density or likeliness of going to the hospital than actual scorpion presence. Also, the map doesn’t indicate actual numbers or a unit of time, so there’s no knowing if the darkest red are so many stings a year, or so many stings a minute. But, it provides a rough idea of who should invest in a hand-held black-light, and who’s most likely to subscribe to weekly pest control.

(We looked at a map of Superfund sites, but everyone has to prioritize their own worries). Such a map is to the right: the darkest areas show the areas with the most stings reported, so it’s more likely to reflect factors such as human population density or likeliness of going to the hospital than actual scorpion presence. Also, the map doesn’t indicate actual numbers or a unit of time, so there’s no knowing if the darkest red are so many stings a year, or so many stings a minute. But, it provides a rough idea of who should invest in a hand-held black-light, and who’s most likely to subscribe to weekly pest control.

Oddly, the scorpion-rich areas are not all desert neighborhoods as you might expect: there’s a hot spot in Tempe with lawns and sprinklers and rose-bushes, and another in the central corridor of older Phoenix. We’ve got friends who live there, and they see scorps way more often than we do, and have been stung. As a kid in Phoenix, I remember being afraid of scorpions after hearing stories of people leaving wet washcloths on the bathroom floor, and finding several of them clinging to the underside of it when it was picked up next morning. (Scorpions love getting under things and hanging there upside down. Biologists call this “reverse geotaxis”: the habit of aligning yourself in reverse to the surface of the earth.) Fortunately, in our area, for most people the sting of most scorpions is a painful inconvenience, and nothing more. There are places in the world where there are much more potent scorps, and their sting is a medical matter and is even occasionally fatal.

After its photo-session, I released this striper in the back yard, under a Cenizo bush, where it clung to some foliage. By the time the sun strikes the plant, it’ll be back in a hidey-hole until night falls again.

(Photo A.Shock; scorpion wrangling E.Shock)