Too Many TOES: Pentadactyly in the Studio…

…with a guest appearance by Charles Darwin

Pentadactyly, from Greek πέντε “five” plus δάκτυλος “finger”, is the condition of having five digits on each limb.

I make a lot of TOES. Gila monster toes. Crane toes. Jaguar toes. Hummingbird toes, owl toes, and roadrunner toes. Toad toes. A lot of TOES.

For the last week, I’ve been detailing Horned Lizard effigy bowls. This involves rendering a lot of small features like scales, horns, cloacal slits, pineal glands, and TOES. So it takes a long time, and that length of time is repeated for each horned lizard bowl, leaving plenty of opportunity for wistful thought about such subjects as, how can I finesse five toes on each tiny, fragile, rapidly hardening clay foot, and would anyone notice if there were only four?

“What could be more curious than that the hand of man formed for grasping, that of a mole, for digging, the leg of a horse, the paddle of a porpoise and the wing of a bat, should all be constructed on the same pattern and should include similar bones and in the same relative positions?” –Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

Okay, so Charles Darwin would notice. Darwin suggested pentadactyly was strong evidence in support of evolution. So, five digits is significant. A horned lizard has five digits on each limb, just like us, and just like many other animals, whether they are lizards, bats, or whales. With some exasperation, I realized I had no idea why this was — why five?

Needing a break from TOES, I headed to the computer: this is what the Internet is for. A quick search on the web produced the slick answer that we all have five digits because the ancestor of all tetrapods (four-limbed organisms) had five digits, and any modern organism that doesn’t (snakes, horses, most birds, etc) has lost digits through evolution. Well, alright so far as it goes — although it’s more of a description than an explanation — but why didn’t the ancestral tetrapod have 8 digits, or 4, or some other number?

It turns out they did: 8, and 6 and 7, among others. In the last few decades, paleontologists have found some fascinating tetrapod ancestors with a variety of phalangic arrangement probably related to the shift from fins to feet, at least partially connected with the shift from aquatic life to life on solid land. Does all this sound inconclusive? That’s because the significance of “Why Five?” is still being manhandled, pinched and slapped around with the discovery of each new ancient tetrapod, mostly in the North Atlantic land areas like Greenland and Scandinavia, which used to be swampy and warm, prime habitat for critters who wallowed in and out of muddy shallows on iffy substraits.

It turns out they did: 8, and 6 and 7, among others. In the last few decades, paleontologists have found some fascinating tetrapod ancestors with a variety of phalangic arrangement probably related to the shift from fins to feet, at least partially connected with the shift from aquatic life to life on solid land. Does all this sound inconclusive? That’s because the significance of “Why Five?” is still being manhandled, pinched and slapped around with the discovery of each new ancient tetrapod, mostly in the North Atlantic land areas like Greenland and Scandinavia, which used to be swampy and warm, prime habitat for critters who wallowed in and out of muddy shallows on iffy substraits.  Think Muddy Mudskipper, but Big, and with weird feet. Lots has been written about this, if you crave more detail than can be supplied here, check out an older but seminal essay by Stephen Jay Gould, “Eight (or Fewer) Little Piggies” and Jenny Clack’s website. She’s a professor at Cambridge University in the UK, and seems to be the reigning Queen of Early Tetrapod Research Especially As It Relates to Limb Development. (The image above of Acanthostega is from her site.)

Think Muddy Mudskipper, but Big, and with weird feet. Lots has been written about this, if you crave more detail than can be supplied here, check out an older but seminal essay by Stephen Jay Gould, “Eight (or Fewer) Little Piggies” and Jenny Clack’s website. She’s a professor at Cambridge University in the UK, and seems to be the reigning Queen of Early Tetrapod Research Especially As It Relates to Limb Development. (The image above of Acanthostega is from her site.)

Which brings me back to toad TOES (regular toad, not horned “toad”). As sometimes happens while riffling though the internet, I didn’t find an exact answer to my original question. But a lot of useful info accrued along the way. Like, now I know something I’d had a hard time finding out from pictorial sources, and forgot to count on the Couch’s spadefootlets: how many toes does a toad sport on its front feet? The answer is four (five on the back feet, the opposite of cats), and the next time I make a toad, I’ll have the right number. And be thankful, because it could have been eight.

Cranky Owlet was unclear on the concept…

...and cast a pellet as well as a VOTE!

Autumnal Owlinox — new season, new yard bird

Last night was a busy night in the yard. Well, I suppose they’re all busy nights, but last night I was awake to appreciate it. Before human bedtime, the geckos were at their posts under the porch lights (our yard residents are the non-native Mediterranean Geckos, not the indigenous Western Banded, but they’re still charmingly rubbery voracious devourers of insects, especially moths), and the Butte was going off sporadically, the coyote pack’s yelps ricocheting off the slickrock. There might have been the sharp yip of a Gray Fox, which also inhabit the neighborhood, but it was faint. Somewhere, the spadefootlets must have been hopping around foraging in the dark, as well.

After “bedtime” though, things really got going. A female raccoon marauded past the bedroom trailed by at least one kit from this year. Last year there were two separate families, one with two, the other with three kits each. That’s a lot of pounds of raccoons living off the yard, plus Papa, too, who has only half of a tail, diminishing his raccoon-gestalt but not his swagger. We’re not sure how many there are this year, because our view of them is most often through the arcadia door, and sightings are limited to who rolls by the framed glass, like watching a dog show on the TV animal channel.

After “bedtime” though, things really got going. A female raccoon marauded past the bedroom trailed by at least one kit from this year. Last year there were two separate families, one with two, the other with three kits each. That’s a lot of pounds of raccoons living off the yard, plus Papa, too, who has only half of a tail, diminishing his raccoon-gestalt but not his swagger. We’re not sure how many there are this year, because our view of them is most often through the arcadia door, and sightings are limited to who rolls by the framed glass, like watching a dog show on the TV animal channel.

Last night the main event (for me), however, was again being awakened by an owl. Not the Great Horned owl this time, but an owl I’d never heard in our yard: a Western screech owl. They’re not uncommon in the area — I’ve seen them peering out from day-roosts in saguaro cavities at the nearby Desert Botanical Garden — but we’ve never heard or seen them in our little scrap of modified desert. This one called from just after 2 am until the Butte really exploded about half an hour later, when the owl stopped. Its mellow short hoots were emitted in a cluster which descended slightly at the end. It sounded much like the “Morse code call” of its cousin the Whiskered screech owl, but that species doesn’t live in this part of Arizona. The call was soft but regular, and started up again at 4 am, and went on for at least 45 minutes, when I fell back to sleep.

So far, like the generously rainy Monsoon of 2008, this has been a generously owly season in the yard, and this Western screech owl, who may always have been here, or who may be a new neighbor, ushered in fall last night; I’m glad I was awake to hear it. With luck maybe we’ll catch a glimpse of it sometime, hunting pocket mice and crickets under the desert trees. Right now, though, I think I need a nap: the first nap of Autumn!

“The northern autumnal equinox takes place today, Monday, Sept. 22nd, at 15:44 UT (11:44 a.m. EDT) when the sun crosses the celestial equator heading south for the year. Autumn begins in the northern hemisphere, and spring in the southern hemisphere. Happy equinox!” (Spaceweather.com)

***

Photos: Raccoon family, A.Shock. Western screech owl by L.Kovash. Left: a Western screech owl peering from a saguaro vessel (stoneware, 12″), from Three Star Owl. Photo by A.Shock.Yard List — Great Horned Owl

Last night at 3.00am exactly, I heard the Great horned owl call. Very close, somewhere right in the back yard. The windows were open because a light monsoon event had brought fresh rain-cooled air, so the call, though soft, carried clearly.

Great horned owls are regulars in our area because there are plenty of perches, and plenty for them to eat. A favorite owly destination is a big Aleppo pine in our back yard. At night that tree is stuffed with roosting doves and other perching birds, a veritable Fresh and Easy for owls. Sitting outside at dark with friends, we’ve watched a horned owl glide stealthily into mid-level branches and then listened as panic ensued among the roosting doves as the owl hopped between branches as if it were going aisle to aisle in a grocery store, filling a cart. Finally it burst out of the needles with a meal clutched in its talons. We got a good look at it is it slid past us, sihouetted against the lights of the house. The feather pool under the pine the next morning was evidence that it had enjoyed a bit of mourning dove.

They are not called “Flying tigers” for nothing. Horned owls, like toadlets, will eat anything that moves and fits down the gullet. Rock squirrels, snakes, desert cottontails, other birds (even other owls), insects, and bats — all are fair game. Even small pets may be at risk, if left unsupervised after dark. The first owl I ever saw was at the family dinner table when I was a kid: a thump, a commotion, and we looked up to see the underside of a Great horned owl pressed to the window, wings flapping against the glass. The owl was trying to separate the family cat (a calico named Ringo, to give you an idea how long ago this was) from the window ledge. A grown cat is awfully heavy prey, however, and the owl had to give up after a few seconds. No one was hurt, but the bird went away hungry. (It was a spectacular view of an owl in action, and I’ve wondered if that was THE bird for me, in a formative sense — I was no more than seven). The boldest hunters are often adults with young to feed — a nest full of hungry owlets requires a lot of sustenance. During that time of the year, parent owls sometimes can be seen hunting even during daylight, working a day job to put food on the table. So, hatching and fledging are timed to coincide with the local peak of yearly rodent production, usually spring, but in the desert areas often much earlier.

They are not called “Flying tigers” for nothing. Horned owls, like toadlets, will eat anything that moves and fits down the gullet. Rock squirrels, snakes, desert cottontails, other birds (even other owls), insects, and bats — all are fair game. Even small pets may be at risk, if left unsupervised after dark. The first owl I ever saw was at the family dinner table when I was a kid: a thump, a commotion, and we looked up to see the underside of a Great horned owl pressed to the window, wings flapping against the glass. The owl was trying to separate the family cat (a calico named Ringo, to give you an idea how long ago this was) from the window ledge. A grown cat is awfully heavy prey, however, and the owl had to give up after a few seconds. No one was hurt, but the bird went away hungry. (It was a spectacular view of an owl in action, and I’ve wondered if that was THE bird for me, in a formative sense — I was no more than seven). The boldest hunters are often adults with young to feed — a nest full of hungry owlets requires a lot of sustenance. During that time of the year, parent owls sometimes can be seen hunting even during daylight, working a day job to put food on the table. So, hatching and fledging are timed to coincide with the local peak of yearly rodent production, usually spring, but in the desert areas often much earlier.

Our local owls have reproduced, and sometimes I’ve heard the distinctive, raspy oink of a horned owlet begging, installed on the top of a phone pole while its parents search the alleys for rats or young cottontails to stuff into it. (If you enjoy camping, you’ve heard a sound like it: the creak made by the plastic hinge on a cooler lid when it’s raised.) The female makes the same sound during courtship while soliciting her mate for food. In our area, courting owls can be seen and heard duetting on phone poles and rooftops, visible against the fading sunset sky. As they call together or alternately — the male and female have slightly different voices and cadences — they bow and “hoo.” She holds her tail up, soliciting attention from the male, who strikes a courtly pose to “sing,” tail raised and wings down, maximizing himself like an operatic baritone (he’s smaller than her). Here’s an excellent quote, where the author’s voice slides from ornithologist to owl, almost inadvertently:

installed on the top of a phone pole while its parents search the alleys for rats or young cottontails to stuff into it. (If you enjoy camping, you’ve heard a sound like it: the creak made by the plastic hinge on a cooler lid when it’s raised.) The female makes the same sound during courtship while soliciting her mate for food. In our area, courting owls can be seen and heard duetting on phone poles and rooftops, visible against the fading sunset sky. As they call together or alternately — the male and female have slightly different voices and cadences — they bow and “hoo.” She holds her tail up, soliciting attention from the male, who strikes a courtly pose to “sing,” tail raised and wings down, maximizing himself like an operatic baritone (he’s smaller than her). Here’s an excellent quote, where the author’s voice slides from ornithologist to owl, almost inadvertently:

“Courtship is fairly boisterous and involves bowing, bobbing, posturing, vocalizing, and allopreening. These elaborate activities lead, as one might hope, to copulation.” (from Hans Peeters, Field Guide to Owls of California and the West, my current favorite owl sourcebook. In the same series as the excellent book on Horned lizards, the California Natural History Guides, published by the UC Press)

If it’s still light enough while all this is going on, you can see flashes of white feathers at their throats, the “gular patch”, flashing as each hoot puffs the owl’s throat briefly. It’s a semaphore for them, like the feather tufts on the top of the head: a way of producing meaningful signals to each other: facial expressions without flexible tissue like lips or eyebrows.

As big, powerful generalist predators, Great horned owls can make it almost anywhere. Their range is right across the US and Canada through Central America and into northern South America. They live in urban, rural, and wilderness areas: desert, woodlands, mountains, wetlands, grasslands and cities, so the chances are you have them where you live, too. Keep an eye open, an ear cocked, and the Chihuahua in at night.

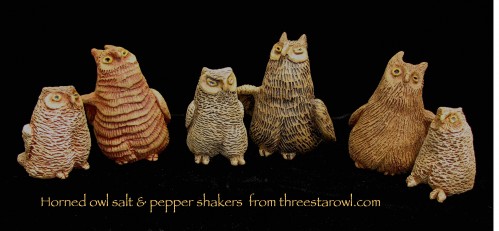

Below are Horned owl salt and pepper shakers from Three Star Owl. Each pair is an adult with an owlet in different stages of development ($48/pair).

Couch’s spadefoots: Tons of tiny toadlets!

My friend Kathy gave me a bucket of toads. Twenty five tiny toads, actually Couch’s spadefoots (Scaphiopus couchii) to be precise. Spadefoots are toadlike amphibians, with their own family, Pelobatidae (see etymological note below). They’re native to the Sonoran desert, and their reproductive cycle is timed to take advantage of summer monsoon rains, needing only 7-8 days to go from egg to tadpole to toadlet. In between monsoon seasons, the adults stay buried deep in the soil of sandy washes to keep from drying out. They can stay buried for 8-10 months at a time, until storms bring the right conditions for them to feed and breed. The sheep-like bleating

My friend Kathy gave me a bucket of toads. Twenty five tiny toads, actually Couch’s spadefoots (Scaphiopus couchii) to be precise. Spadefoots are toadlike amphibians, with their own family, Pelobatidae (see etymological note below). They’re native to the Sonoran desert, and their reproductive cycle is timed to take advantage of summer monsoon rains, needing only 7-8 days to go from egg to tadpole to toadlet. In between monsoon seasons, the adults stay buried deep in the soil of sandy washes to keep from drying out. They can stay buried for 8-10 months at a time, until storms bring the right conditions for them to feed and breed. The sheep-like bleating of the singing male spadefoot is an archetypal sound of the Sonoran desert. Some Arizona tribes associate toads and owls with monsoon rain, and that’s the origin of the fanciful Three Star Owl piece “Two-Toad Owl“.

of the singing male spadefoot is an archetypal sound of the Sonoran desert. Some Arizona tribes associate toads and owls with monsoon rain, and that’s the origin of the fanciful Three Star Owl piece “Two-Toad Owl“.

These little spadefoots hatched in a standing pool in Kathy’s Scottsdale yard, where they’re plentiful. They’re very tiny — each could sit on a penny. They’re so small that it wasn’t until I saw the close-up photos that their emerald green eyes were noticeable. If you’ve never nourished toadlets, they’re easy to feed: if it moves and fits in the toadlet’s mouth, they’ll eat it. These guys have been snarfing up crickets, and other protein-rich yummies like Miller moth larvae from birdseed (and an old bag of flour!).  Even ants will go down the hatch, as long as it’s not one of the larger soldiers, which put off a noxious chemical. The one on the left was photographed before the first cricket feeding; it plumped up noticeably after downing a small cricket or two.

Even ants will go down the hatch, as long as it’s not one of the larger soldiers, which put off a noxious chemical. The one on the left was photographed before the first cricket feeding; it plumped up noticeably after downing a small cricket or two.

But I’m not keeping them in captivity. Once they’re fed up, I’ll release them in our yard at twilight, where hopefully they’ll replenish our neighborhood population. Releasing them after dark will give them a head-start over the foraging Curve-billed thrashers and Cactus Wrens. A couple years ago, we would hear male spadefoots bleating like lambs after a big rainstorm, and one or two would end up in the pool, looking for somewhere to breed. But recently, we haven’t heard or seen any. So I’m hoping these guys get things going again. Good luck, little spadefoots, and ‘ware Raccoons and Coachwhips!

Photos: the adult spadefoot photo is from the US Fish & Wildlife site on Arizona Amphibians. The other photos are by A. Shock. Excellent photos and still more info about Couch’s spadefoot can be found at Firefly Forest — check it out.

Etymolgical note and stray ornithological note

About the term “spadefoot”: It comes from the small, hard digging appendage on the underside of the back legs of these amphibians. Members of the family Pelobatidae are not considered “true” toads, so it’s proper to call them simply “spadefoots”. Pelobatidae, the family name for all Spadefoots, comes from a Greek word, pelobates (πηλοβατης), literally “mud-walker”. A nice tie-in for a potter is that the first element of this word comes from the Greek word pelos, meaning “clay”, specifically the clay used by potters and sculptors.  The genus, Scaphiopus, is constructed of two Greek elements and means “spade-foot”. The species name, couchii, comes from the surname of Darius Nash Couch, a U.S. Army officer who, during leave in 1853/54, traveled as a Smithsonian Institute naturalist to Mexico, where he collected specimens of both the Couch’s Spadefoot, and Couch’s Kingbird, a tyrant flycatcher native to south Texas and the gulf coast of Mexico. Out-of-range Couch’s kingbirds occasionally show up in Arizona. Recently, a Couch’s kingbird has wintered in Tacna in southwest Arizona, eating bees and behaving like a tyrant flycatcher.

The genus, Scaphiopus, is constructed of two Greek elements and means “spade-foot”. The species name, couchii, comes from the surname of Darius Nash Couch, a U.S. Army officer who, during leave in 1853/54, traveled as a Smithsonian Institute naturalist to Mexico, where he collected specimens of both the Couch’s Spadefoot, and Couch’s Kingbird, a tyrant flycatcher native to south Texas and the gulf coast of Mexico. Out-of-range Couch’s kingbirds occasionally show up in Arizona. Recently, a Couch’s kingbird has wintered in Tacna in southwest Arizona, eating bees and behaving like a tyrant flycatcher.