What happened at Beit Bat Ya’anah: part 4

This is the fourth installment of a series. Click on the link at the bottom of the page to continue to the next installment. Or, click here to read from the very beginning. Previously:

Wayfarer was warming to her subject, the possible unsecured antiquity. “So you might say that we’re looking for an object like everything else around it, but not quite: an artifact with an accent.” “Well, the generator goes off at nine pm sharp,” Rankle interrupted her,” so if you’d like to see your little unsecured antiquity in the light, you’d better do it soon.”

The Unsecured Antiquity

Professor Einer Wayfarer hadn’t wanted an audience for her first view of the mystery object that had brought her to Beit Bat Ya’anah, but ultimately it hadn’t been possible to avoid it. She supposed it was her own fault: after her spirited exposition at dinner, everyone wanted to see what she was going to do. She felt she couldn’t refuse to satisfy the students’ curiosity – it was a legitimate educational opportunity for them – so she found herself following Wilson A. Rankle, marching downhill across the rough, stony soil of the moonlit compound to the lab, trailing a string of students and staff behind.

The one-room lab was the dig camp’s only intact hard-sided structure, left over from a failed settlement attempt in an earlier decade. Although recently painted, it was both shoddily built and structurally weathered – and it smelled like dry rot and insecticide – but inside there were cabinets and file drawers, a couple of light-tables, writing tables with archaic wooden school chairs with green backs and split black vinyl seats, and a banged-up dry sink that at night collected a surprising assortment of joint-legged samples of the local fauna that, once in, couldn’t escape its vertical sides. If the lab had housed a entomological research effort, this sink would have had appreciable scientific value, but as it was, everyone was merely repelled by what showed up in the porcelain trap every morning, and devised ways of not being the first one in who, by convention, had to liberate the leggy zoo with a four-by-six file card and a jam jar.

it was both shoddily built and structurally weathered – and it smelled like dry rot and insecticide – but inside there were cabinets and file drawers, a couple of light-tables, writing tables with archaic wooden school chairs with green backs and split black vinyl seats, and a banged-up dry sink that at night collected a surprising assortment of joint-legged samples of the local fauna that, once in, couldn’t escape its vertical sides. If the lab had housed a entomological research effort, this sink would have had appreciable scientific value, but as it was, everyone was merely repelled by what showed up in the porcelain trap every morning, and devised ways of not being the first one in who, by convention, had to liberate the leggy zoo with a four-by-six file card and a jam jar.

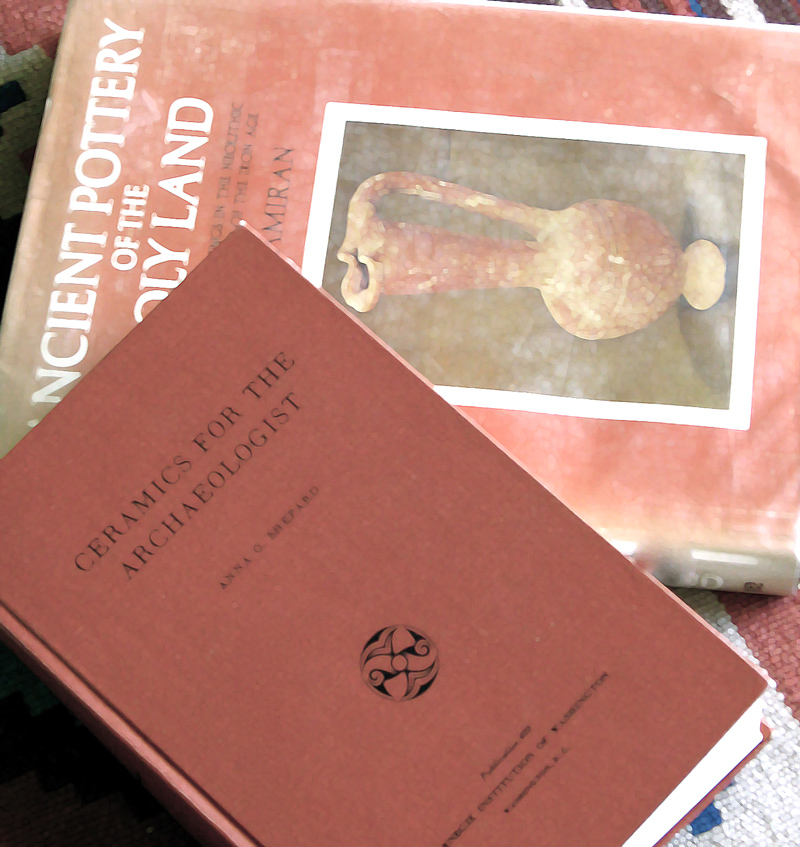

All the lab’s windows were high on the block walls. Many were painted shut, and those that weren’t opened just wide enough to let in small puffs of hot air and large numbers of moths and scarabs. The lighting was better than anywhere else in the compound, but still barely adequate for night work. This was where the senior staff and a handful of conscripted underlings worked afternoons and after dark, until the generator shut down, writing up daily reports, plotting features and matrices on maps of units, and recording on cards anything significant that came out of the ashy soil that day, which was a rare event. There was a skeleton library with basic resources: a beat-up first edition of Aharoni’s book in Hebrew, Shepard’s and Amiran’s books adjacent,  dated but still useful, a few back issues of the BAR and JNES, and monographs and annual reports from other sites. There was one electric fan whose weak output everyone fought over except Shams, the dig’s meticulous draftsman/surveyor, who never sweated and was seldom seen without his stingy-brimmed panama hat, and who didn’t want a feeble breeze stirring his ink renderings even a little.

dated but still useful, a few back issues of the BAR and JNES, and monographs and annual reports from other sites. There was one electric fan whose weak output everyone fought over except Shams, the dig’s meticulous draftsman/surveyor, who never sweated and was seldom seen without his stingy-brimmed panama hat, and who didn’t want a feeble breeze stirring his ink renderings even a little.

Now Shams, Zvia, Rory, about eight other grad students and staff plus the one eager undergrad named Eric – his neck still blotched and hot from the wasp stings – were sitting in the hard green chairs watching William A. Rankle rummage through a drawer.

“Where the hell is it, Ben-Tor?” he grumbled. It occurred to Wayfarer that the director didn’t know what he was looking for. Zvia went over and directly pulled a plastic bag out of the drawer he was disarranging. “Those are all in locus order, please, Dr. Rankle,” she pointed out, firmly. “Here; Dario said it’s this one.”

This reminded Rankle again of his missing staff member. He looked around, as if the young man might have somehow recently manifested. Not finding him, he asked, “Where did you say he is?” No one answered.

Wayfarer received the bag from Zvia, hefting it in her palm: it was weighty for its volume, but not large. She asked, “May I handle it?”

Rankle laughed. “Knock yourself out. It’s nothing special. Despite what Dario says.”

Dr. Wayfarer noticed Zvia turn slightly pink at the last part of this remark, as if it were directed at her. “Everyone’s an expert, aren’t they?” the professor commented neutrally as she took the object out of the plastic bag, and laid it on the table. Then she pulled out her glasses, and perched them on the end of her nose to take a good long look at the Object.

Evidently the AWOL Dario, whoever he was, had a sense of humor: after staring at it for no more than thirty seconds, she declared authoritatively, “Well, it’s definitely not a spoon.”

What she had placed on the table – the “mystery object”, the much-anticipated unsecured antiquity – appeared to be nothing more than a lump of broken pottery: a handle, evidently broken off of a medium-sized vessel, with a fragment of neck joining the two ends. There was no sign of surface decoration, such as glaze, slip or incision. The clay body was gritty and brown, and the item was neatly if casually formed. But Wayfarer wasn’t an archæologist; the unrefined ceramic fragment meant little to her, yielded nothing to her inexpert examination. She cleared her throat; a noise that sounded distinctly like hrrmph. “Someone tell me about the type of vessel this comes from. Please.”

Rankle prompted, “Ben-Tor?”

“Pottery man did that one,” Zvia said. “Since Amit wasn’t here.”

“Pottery man” — Amit’s grad student Lior — spoke up promptly, “Fragment; strap-handle. Probably from an amphora; retrieved from an Iron Age exterior residential midden, stratigraphically undatable; maybe a small Canaanite jar, originally for transport, maybe afterwards re-used for domestic wine storage.”

Wayfarer hrrmphed again; it was the closest she was going to get to wine tonight, apparently. But she nodded at Lior, summarizing, “An undatable storage jar handle. Thank you.” She placed her finger in the loop of clay and held the fragment up once more. The shape was unremarkable, the construction was unremarkable. It was merely household waste; part of a broken, discarded wine jar. Very disappointing. Worse yet, she found herself in agreement with Rankle: the object was nothing special. It was an unremarkable fragment altogether, with nothing at all to recommend it for her further notice.

She was about to say so when something stopped her. Pulling her blunt finger out of the handle and looking underneath it for the source of a sensation of roughness against her skin she asked, “Does anyone have a dental mirror?” One was handed to her, and she slid it under the strap of clay.

On the underside of the handle, where it was invisible to the eye but would have been felt with the fingers of anyone picking up or pouring the vessel, the mirror reflected a small textured mark. It had been pressed into the clay while still soft: a geometric, elemental symbol that was very familiar to Dr. Wayfarer within the narrow context of her own literary subject.

Was this what Avsa wanted her to see – not a piece of pottery, but a character? Characters she knew something about. A character, Wayfarer thought, she might be able to do something with.

Characters she knew something about. A character, Wayfarer thought, she might be able to do something with.