Yard list — Miss Thang

Meet Miss Thang. She is a female Costa’s hummingbird (Calypte costae), and unlike her purple-mustachioed male counterpart, she’s a plain green-gray above, and a plain gray-white below, with a chunky round body, almost no tail, and no neck at all. She holds territory right outside our front door, as Queen of the Desert Garden. The garden has many attributes valuable to a hummer: twiggy mesquites for roosting, a many-pointed DeSmet agave for perching, chuparosas with long-season blooms to feed upon, a freebie sugar-water feeder under the porch, and best of all, prime position from which to attract a showy male Costa’s who does looping, zizzing display flights for her each morning. Although Miss Thang’s appearance is subdued, her personality isn’t. She holds this valuable, resource-rich territory against all comers, including resident male Anna’s who are both brash and bigger, the summer tourists like Black-chinned hummingbirds, and any other hummers who may try to kype a slurp from the feeder. The Gila woodpeckers are too big to chase off, and the Verdins seem to come and go with impunity, but other hummers at the feeder are given short shrift. Speedy tail chases through the mesquite are frequent, although peevish scolding from a perch sometimes inches above the ground are often sufficient to rout invaders. Her favorite perch from which to keep an eye on her real estate is a devil’s claw and obsidian wind chime, situated under the porch overhang directly outside the front door, shaded in the mid-day warmth, and dry in the rain. At this time of year, when the door is open most of the day, we can see her perched alertly on the point of the devil’s claw for hours, spinning slowly as the chime turns in the breeze, chattering indignantly when another hummer flies through, or sallying forth to escort strangers right out of the yard.

Meet Miss Thang. She is a female Costa’s hummingbird (Calypte costae), and unlike her purple-mustachioed male counterpart, she’s a plain green-gray above, and a plain gray-white below, with a chunky round body, almost no tail, and no neck at all. She holds territory right outside our front door, as Queen of the Desert Garden. The garden has many attributes valuable to a hummer: twiggy mesquites for roosting, a many-pointed DeSmet agave for perching, chuparosas with long-season blooms to feed upon, a freebie sugar-water feeder under the porch, and best of all, prime position from which to attract a showy male Costa’s who does looping, zizzing display flights for her each morning. Although Miss Thang’s appearance is subdued, her personality isn’t. She holds this valuable, resource-rich territory against all comers, including resident male Anna’s who are both brash and bigger, the summer tourists like Black-chinned hummingbirds, and any other hummers who may try to kype a slurp from the feeder. The Gila woodpeckers are too big to chase off, and the Verdins seem to come and go with impunity, but other hummers at the feeder are given short shrift. Speedy tail chases through the mesquite are frequent, although peevish scolding from a perch sometimes inches above the ground are often sufficient to rout invaders. Her favorite perch from which to keep an eye on her real estate is a devil’s claw and obsidian wind chime, situated under the porch overhang directly outside the front door, shaded in the mid-day warmth, and dry in the rain. At this time of year, when the door is open most of the day, we can see her perched alertly on the point of the devil’s claw for hours, spinning slowly as the chime turns in the breeze, chattering indignantly when another hummer flies through, or sallying forth to escort strangers right out of the yard.

Costa’s are desert hummingbirds. They range from southern California, across the low deserts of Arizona, into Mexico. The sources I’ve checked supply varying info about the yearly movements of Costa’s, giving an impression of the need for more research. Some experts report they winter just south of our border with Mexico, others say the birds stay year-round in the low desert, some that they winter in the ‘burbs and breed in the less developed areas of the deserts; others just assert that their distribution is not well known. In our yard in some years, Costa’s seem to be present in each month, with the largest number of individuals observed between June and December. Some years they seem to disappear around the New Year and are scarce until late spring. Now that we’ve packed the yard with hummer-friendly flowers (the photo above is Miss Thang’s demesne in full spring bloom) like chuparosa (Justicia californica), Mexican honeysuckle, (Justicia spicigera), Fairy dusters (Calliandra spp.), Desert lavender (Hyptis emoryi), native penstemons, various aloes, and sugar-water feeders, we seem to see more birds more of the year.

There’s been a female Costa’s hummer holding our front-garden territory year-round for at least two years. We have no way of knowing for sure that it’s always Miss Thang, but of course it’s possible — it even seems likely. We suspect she nests nearby — I’ve seen her gathering spider-webs in her beak — but have never discovered a nest. (Each year we do see young-of-the-year Costa’s in the yard, but we don’t know where they hatched.)

The yard also hosts glorious males, staking out other food-plant and feeder-related territories. In past years, a Little-leaf Palo Verde was favored by a bird we called “Cornerhead” because his gorget went from scraggly sideburns to full-blown Yosemite Sam whiskers over the summer into fall. This is his picture on the right. This year, there’s a long-mustached male (it may be Miss Thang’s suitor) under the pine/palo verde complex shading an outdoor table. He “sings” (an almost inaudibly high-pitched descending sibilance) and gnats under the branches, keeping interlopers off the feeder there, then withdraws to the thorny interior of a nearby lemon in the middle of the day. He “sings” from there, too, invisibly in the deep shade which is the only reason we know he’s in there.

The yard also hosts glorious males, staking out other food-plant and feeder-related territories. In past years, a Little-leaf Palo Verde was favored by a bird we called “Cornerhead” because his gorget went from scraggly sideburns to full-blown Yosemite Sam whiskers over the summer into fall. This is his picture on the right. This year, there’s a long-mustached male (it may be Miss Thang’s suitor) under the pine/palo verde complex shading an outdoor table. He “sings” (an almost inaudibly high-pitched descending sibilance) and gnats under the branches, keeping interlopers off the feeder there, then withdraws to the thorny interior of a nearby lemon in the middle of the day. He “sings” from there, too, invisibly in the deep shade which is the only reason we know he’s in there.

Etymology…

…of the scientific name of Costa’s hummingbird, Calypte costae, is less than satisfying. On the genus, Calypte, Choate, in the Dictionary of American Bird Names, can’t do any better than “Greek, a proper name of unknown significance”. If he were alive, Gould could probably give a better explanation as to why he chose this genus for the bold Anna’s and Costa’s hummers. I would suggest that Gould had in mind the adjective καλυπτή, from the verb καλύπτειν, to cover (with a thing). The adjective means “enfolding”, connoting a veiled or mantled quality, possibly referring to the gorget that covers the entire crown and throat of hummers in this genus. As for the species, costae, that was given in honor of Louis Marie Pantaleon Costa, Marquis de Beau-Regard, which early 19th century French nobleman had an “imposing” collection of deceased hummingbird specimens. Merde, alors.

Photos: All photos by A. Shock, Three Star Owl. The odd quality of the first photo of Miss Thang is due to the image being shot through an old-fashioned heavy metal security screen.

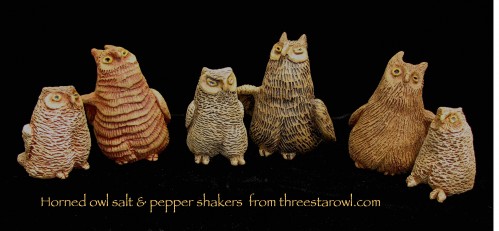

Here is an image of a Costa’s hummingbird mug from Three Star Owl. The interior is a beautiful rich mulberry, the glaze color I can manage closest to the color of a male Costa’s gorget.