What happened at Beit Bat Ya’anah: part 12

This is the twelfth installment of a series. There’s a link at the bottom of the page to the thirteenth installment. Read Part 11 by clicking here, or start at the very beginning by clicking here.

Previously:

After encountering an anomalous fragment of pottery decorated with a bee and a possible flower, the Beit Bat Ya’anah staff were hotly debating its origins. Leaving them to it and wandering out across the moonlit compound, Professor Wayfarer had recalled a fragment of poetry with a similar motif, causing her to wonder who the people were who had made this rocky site their home.

After encountering an anomalous fragment of pottery decorated with a bee and a possible flower, the Beit Bat Ya’anah staff were hotly debating its origins. Leaving them to it and wandering out across the moonlit compound, Professor Wayfarer had recalled a fragment of poetry with a similar motif, causing her to wonder who the people were who had made this rocky site their home.

The Nature of the Hill: secrets and surprises

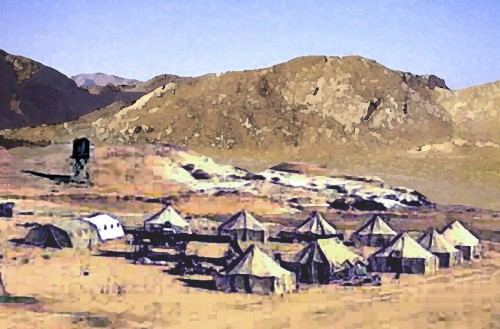

Outside the lab building, Einer Wayfarer glanced at her watch. It was not quite 8.30, and she was ready for bed, unaccustomed to the long active hours on the hill, which were so different from her sedentary days behind a desk in her office, at the library, or in the classroom. She was surprised to find that she could read the hands of her wristwatch in the moonlight – the waxing moon was only slightly more than half full, yet she noticed her squat shadow running ahead of her sharp along the stony ground. In Lassiter the lardy moon was never this bright, even full. Here, colors were discernible in the clear desert moonlight. You could read poetry by it, Wayfarer thought – hell, you could write poetry by it, if you were that sort of person. If you were that sort of person.

As though intent on enabling such romantic pursuits, the moon lit two spots of bright color as the professor passed downhill of the shadowed dining tent: aniline pink hair and a man’s white shirt – two figures, leaning together against the end of one of the tables. Mikka the ex-cook/photographer and the elusive Dario had found a way to pass the evening that didn’t involve tiresome record-keeping in the ill-lit lab.

Unsurprised, Wayfarer looked and then looked away. To judge by the intimacy of their embrace, she concluded that the rearrangement of kitchen duties hadn’t impaired their acquaintance. It occurred to her to sympathize briefly with Avsa Szeringka for having to supervise the young man as a graduate student. He seemed to be expert at simultaneously eluding unwanted contact and attracting attention to himself, a curiously infuriating skill set for an academic advisor to wrangle, and likely to create disruptions in a research setting.

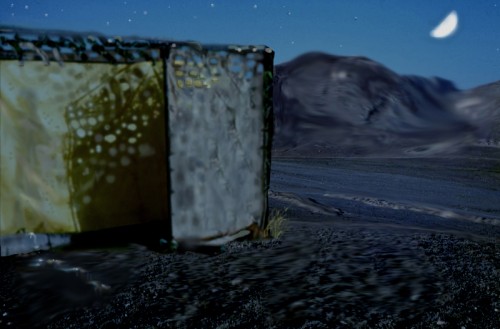

Less earthily and more celestially, it also seemed to Wayfarer that the gibbous moon was in a forthcoming mood, naughtily giving up other people’s secrets to anyone who was paying attention. It would be foolish to not take advantage of its revelations, so she changed her mind about heading to bed. Instead, she climbed upward to the crest of the ridge where she had first stood with Wilson Rankle, just yesterday. She arrived at the top, puffing slightly and disappointed in her hope for a slight breeze.

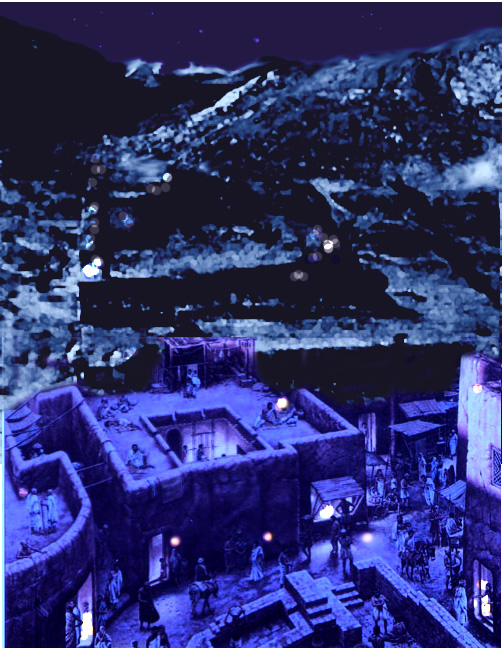

Catching her breath, she looked down on the site. Einer Wayfarer was not superstitious, or prone to fancy. But she was also not unimaginative: over the years, she had acceptably  and productively harnessed an active imagination to the yoke of scholarly creative thought. So although she didn’t expect to see a ghostly diorama of moonlit re-creation laid out before her — an ancient town’s crenellated stone-and-mud walls dimly peopled by long-dead shades of priests and goat-herds and potters and children and soldiers and dogs, shouting and tending smoky cooking fires, chasing screeching chickens, drinking wine, dying clothes, writing letters, and tanning hides — she was open to the possibility that the site, seen quite literally in a new light (to use that well-worn cliché she deplored in less careful academic writers) might show her something she hadn’t observed before, something more human than the dry chronological classifications recited by Wilson Rankle in the glare of daylight.

and productively harnessed an active imagination to the yoke of scholarly creative thought. So although she didn’t expect to see a ghostly diorama of moonlit re-creation laid out before her — an ancient town’s crenellated stone-and-mud walls dimly peopled by long-dead shades of priests and goat-herds and potters and children and soldiers and dogs, shouting and tending smoky cooking fires, chasing screeching chickens, drinking wine, dying clothes, writing letters, and tanning hides — she was open to the possibility that the site, seen quite literally in a new light (to use that well-worn cliché she deplored in less careful academic writers) might show her something she hadn’t observed before, something more human than the dry chronological classifications recited by Wilson Rankle in the glare of daylight.

And she was not too stuffy to wish for a time machine to confirm such imaginings, since the methods of archeologists seemed to her, paradoxically, to be both technically sterile and too subjective all at once. Whereas one could easily imagine these walls long ago corralling all the same activities that people engage in today – cooking, lying, loving, keeping secrets, making mistakes, laughing, prevailing, struggling – it was the surprises, the things you’d never guess, that interested Einer Wayfarer. It was in surprises where progress lay in understanding ancient lives, in fleshing out people who lived long ago. Surprises like a jar handle bearing a hidden ambiguous symbol, a painted bee drawn to an exotic flower on a sherd, and a young man whose tapped initial Rs and slightly retroflected Ss were not fully explained by either southern European origin or Scottish influence.

As she moved along the ridge to a better vantage point, she realized she wasn’t alone. Just ahead of her, perched on a flat rock, sat Amit Chayes.

“Does no one around here sleep?” she asked.

“Sleep? It’s still early,” Chayes said, turning. “Erev tov, Einer. Please sit,” he invited her. “Doing what?”

“Seeing what the moon has to show. And you?”

“The same. And the tables were occupied.”

Wayfarer chuckled. “Danish lessons, do you suppose?”

“I can remember being so young, can’t you?” Chayes smiled. “I met my wife on a dig. These things are to be expected — it’s natural.”

“Indeed it is,” Wayfarer said, not answering his actual question, and doubting the pertinence of matrimony in this instance. “In fact, Rory Zohn was just touting the advantage of working within natural systems, although his example was aptitude for cooking, not sex.”

“If camp gossip is true, perhaps in this case it’s related,” Chayes laughed. “Well, I should spend more time in the lab. I didn’t know discussion there was so intellectual, usually.”

“It seems like you’ve put together a fairly good crew.”

“Young, but good,” he agreed. “Pretty good. Some hard workers, some needing a bit more guidance, more experience. As usual. We were lucky: except for Zvia Ben-Tor, who requested to come, our permit came so late the crew was filled in the last minute with overflow from other site applicants.”

“Why is that?”

“The government is preoccupied with the Lebanese events. And so many archeologists are called up for military service at times like this, the Reshut HaAtikot — the IAA — is slowed down to an even less efficient pace than usual. Our small site had low priority.”

“Why are you digging here, Amit?” Wayfarer asked. She looked out over the hill, onto the squares making an orderly framework deeply cut against the pale, stony hilltop. Within the inky pits were dim outlines of walls and floors, none complete, few rectilinear,  not at all aligned with the carefully surveyed lines of the archæologists’ grid, running their own imprecise, human-laid courses under the sternly oriented, scientifically imposed balks.

not at all aligned with the carefully surveyed lines of the archæologists’ grid, running their own imprecise, human-laid courses under the sternly oriented, scientifically imposed balks.

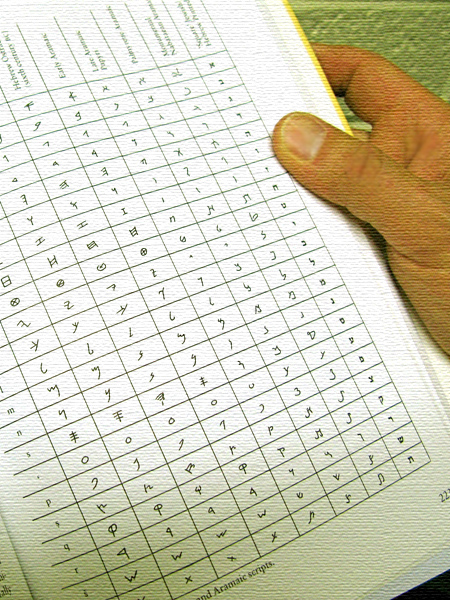

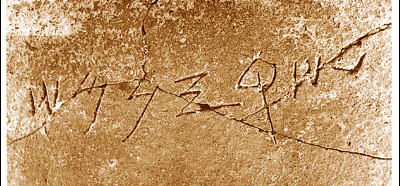

“Ah, the staff have been complaining to you,” Chayes stated, answering her meaning and not her words. “The simplest answer is archeological: because there are so few remains later than the Bronze Age at the site the Chalcolithic and even earlier levels, if present, should be relatively well-preserved. But also…” He glanced over his shoulder at the sheer cliffs that rose above the site a few hundred meters from where they sat. “I think that the place has… Well, to say it has secrets is too dramatic; all archeological sites have secrets; it’s their nature. So, I will say instead surprises. For instance, I was hoping you’d confirm that character on the amphora handle as wehériəl.”

His words resonated uncannily with her earlier thoughts. “You’re looking for evidence of Elennui culture?” Wayfarer asked. “That is a surprise.”

Chayes shook his head, “No; no, I’m not looking. That’s unsound technique in our field: you almost always find what you look for. But, if it were to show up, that would be a surprise.” He shrugged. “So, I hoped the symbol was evidence that Elennui speakers have lived here.”

Wayfarer cleared her throat. “I wish I could have confirmed it, but…”

The archeologist waved a hand. “No; of course. It was sound scholarship, much more important. And no matter – there is still much dirt to move.”

“Who has lived here?” she asked. Responding to Szeringka’s peremptory summons, Wayfarer hadn’t had time to read site reports, and Rankle’s dull orientation had meant little to her.

Chayes paused before responding. “Do you mean people of the Bible?”

She supposed he was accustomed to that question, perhaps irked by it. She replied, “No, that’s not my bias. I simply mean people. Any people, of any book. Or of no book. Who has lived here?”

“This is Israel – who hasn’t lived here? Over the millenia, this ridge has been occupied by foreign soldiers; nomads from far and near; tale-telling hunter-gatherers with stone tools; well-organized patriarchs with scribes and cisterns, pottery and laws; zionist idealists; entrepreneurial ostrich farmers. Optimistic archeologists. People who left things, and people who are looking for those things. People hoping for secrets – surprises. But the site has kept its secrets well, I would say.”

“So, it’s not a tell…” Wayfarer punned, not sure Chayes’s English was colloquial enough to catch it.

He shrugged and made a literal reply. “Our hill is not a tel, technically. Just superimposed occupation levels along a ridge – most of the topography is geologic, natural – piled up outwash from the upper wadi, now eroding slowly. But I understand your joke – and no; it is not a tell, in any sense. Especially in one way,” Chayes added, “the site has been entirely mute. The staff is right – Beit Bat Ya’anah is missing something.”

Wayfarer waited.

“We’ve sounded, and surface-surveyed across the whole ridge, and even searched downstream in the wadi. It’s a small but enduring habitation: one would expect…” the archeologist broke off, then finished bluntly, “No bones, no teeth. No evidence of burials or any human remains.” He shrugged once  again. “Well, as I say, there is much dirt yet to move.” Chayes turned back to the moonlit walls below, perhaps again hoping to be shown secrets, or at least surprises.

again. “Well, as I say, there is much dirt yet to move.” Chayes turned back to the moonlit walls below, perhaps again hoping to be shown secrets, or at least surprises.

Einer Wayfarer took the hint, and stood to go. But she couldn’t keep from asking one more question. “Ostrich farmers?”

“You don’t know the meaning of Beit Bat Ya’anah?” Chayes asked. “ya’anah is the female form of ya’en, ostrich. The name means ‘House of the Ostrich’s Daughter’. Ask Moshe sometime – he loves to tell that story.”