What Happened at Beit Bat Ya’anah: part 8

This is the eighth installment of a series. There’s a link at the bottom of the page to the next installment. Or, to read from the very beginning, click here.

Previously:

The sleek, scented body that had slipped past her in the dark engaged Wayfarer’s academic curiosity: he was no one she’d seen yet on site. Who was he? But then she thought, it hardly mattered; by tomorrow night, she’d be on a plane home.

The dawning

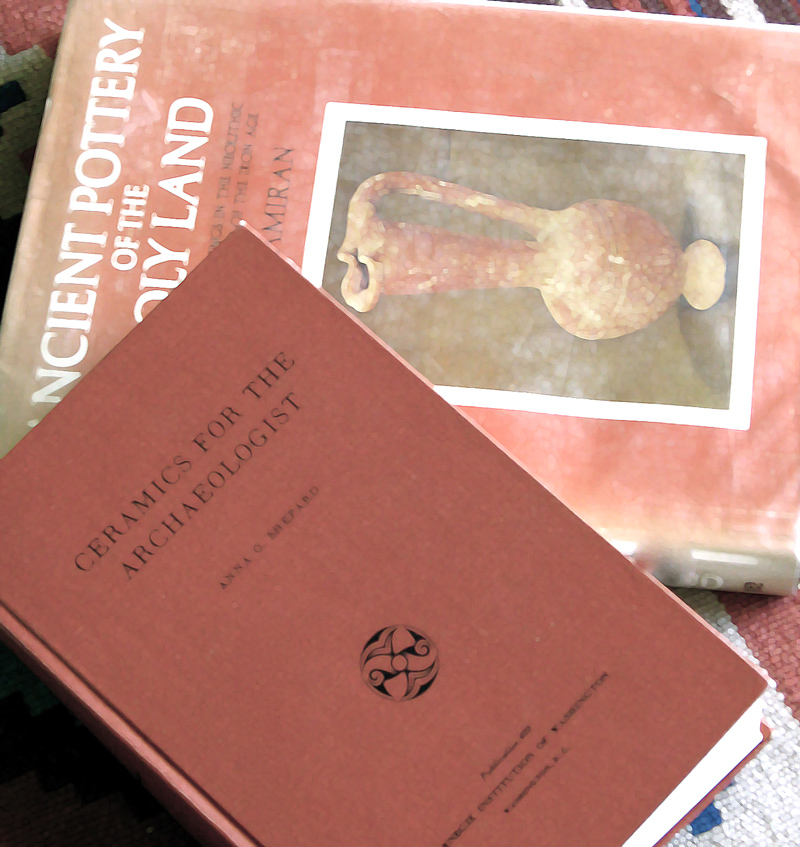

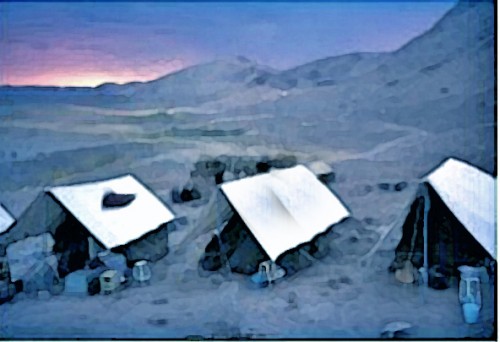

The next morning, or more exactly, forty three minutes since returning to bed after her bootlegged nocturnal shower and six minutes before it was set to sound, Einer Wayfarer’s hand flattened the off button of her wind-up alarm clock. She’d awakened abruptly, her sleep-working brain belatedly aware of what the dripping, moonlit young man’s exact words to her had been. She sat up, and reached under her cot to pull out her brief case. Checking the leather for undesirable arthropods and finding only an innocuous black beetle, she extracted the letter that had brought her to Beit Bat Ya’anah.

brought her to Beit Bat Ya’anah.

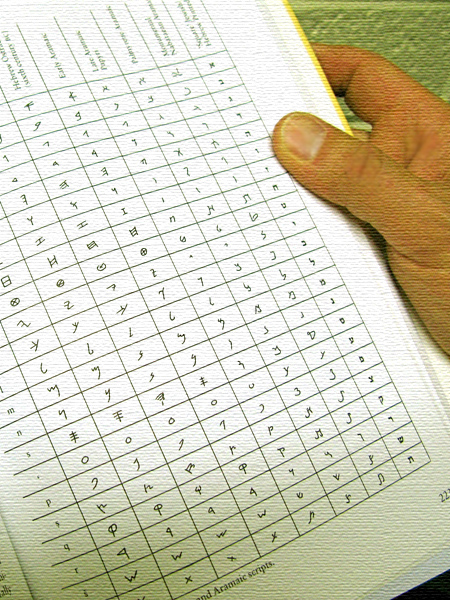

Her colleague’s continental penmanship was difficult to read, especially in what little dawn light filtered through the heavy canvas walls. Besides, English was not Avsa Szeringka’s second language, nor even her third. As a consequence her English style on paper, although as vivid and original as her native thinking, was not as clear. In professional texts, this made Avsa terribly dependent on her editor – Wayfarer had met Melita Matsouris in London and found her to be a very patient and determined woman. But personal missives from Avsa were never professionally wrangled, so they required careful recension. For one thing, they always suffered from swarms of commas. Wayfarer knew this infestation of punctuation was an attempt at clarity, but its effect was the opposite, particularly since they were seldom employed where actually needed.

Squinting a little even with her bifocals on, she ran her eyes down the hastily-written page until she found the portion she wished to re-read:

And also, too by the way, I am aware of a cryptocultural artefact I recommend you acquaint with, at a remote site in Negev, whom I think you would find interesting, and, quite compelling if my belly is correct since, because perhaps, is strongly authentic in style and origin. In a way, a cultural fossil, one might say a fly in amber; you might say maybe an unsecured antiquity. I beg do not be misled by appearance or impression of artefact, somewhat vulnerable, I think important to evaluate and conserve, with care.

Wayfarer’s colleague had added pragmatically and imperiously:

Airfares low, now, because of hot season, and your semester not yet started, so I have contacted Beit Bat Ya’anah, Ben Gurion University, excavation directors Amit Chayes and W.A. Rankle, to inform them of expecting you, later in this month. Therefore, no refusals, if you please, to my request.

Besides the advice on airfare, which had turned out to be accurate, Wayfarer realized that in the entire hash of phrases there was just one critical word, the significance of which she recognized only now: whom. “Whom I think you would find interesting,” referring not to the site, but the artifact. And initially concealed by all the other idiomatic idiosyncrasies, it was not a grammatical error: the vulnerable artifact, the unsecured antiquity, was not what, but who.

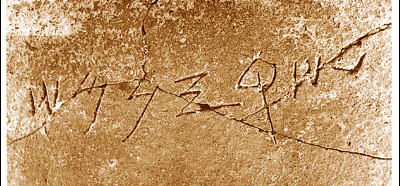

Wayfarer smiled to think how Avsa would laugh when she told her how she’d spent an evening puzzling over an ashy, broken lump of under-fired domestic-ware. And how disappointed Wilson Rankle was going to be when she informed him she wouldn’t be needing a ride back to Beer-Sheva right away: she’d found her “artifact with an accent”  after all, and he had just wished her a fluent good morning in what was agreed by experts to be a thoroughly dead language.

after all, and he had just wished her a fluent good morning in what was agreed by experts to be a thoroughly dead language.

To be continued…

To continue to the next installment, Part 9 “The Trenches”, click here