Wild hogs in the desert…

….but not the quadrupedal kind.

One of the main attractions of following the Castle Hotsprings Road through the edge of the  Buckhorn Mountains NW of Phoenix is the spring wildflower bloom. This past weekend the succulent plants predominated: Ocotillos were in full swing, and the prickly pear were starting to get the hang of it.

Buckhorn Mountains NW of Phoenix is the spring wildflower bloom. This past weekend the succulent plants predominated: Ocotillos were in full swing, and the prickly pear were starting to get the hang of it.

<< one solitary ocotillo bloom leans in close as if to check out the saguaro’s underarms. This one needs a caption, like those dweeby cactus humor books I remember from my childhood. Something like, “Stubble?, umm, I think you missed a spot.” (all photos A. Shock unless noted; click each to enlarge, it’s worth it)

This horizontal Englemann’s pear leaf sprouted buds like shrimp on a plate, instead of just around the top edge (photo E.Shock). >>

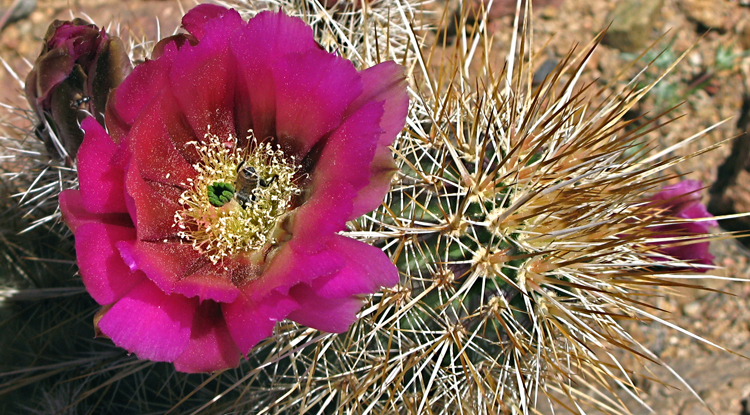

It must have been close to peak for the display of Englemann’s hedgehog cactus (Echinocereus englemannii) in explosive, glorious, hot pink bloom. The stems of these spiny succulents are only about a foot tall and their green skin is concealed by both long and short spines, so despite their numbers, the sturdy hedgehog clumps are easily overlooked for  most of the year. But their pink-to-magenta flowers are up to three inches across, making flowering cactus stand out on the most brutally exposed slopes of rocky hills and arroyos. <<

most of the year. But their pink-to-magenta flowers are up to three inches across, making flowering cactus stand out on the most brutally exposed slopes of rocky hills and arroyos. <<

They don’t need much of anything to grow or bloom — their preferred medium is stony, desiccated, mineral soil, sometimes in the scant shade of a shrub or larger cactus, sometimes not:  they’re happy baking in the full Arizona summer sun, and can thrive in a crack in solid rock that even a rock wren would scorn.>>

they’re happy baking in the full Arizona summer sun, and can thrive in a crack in solid rock that even a rock wren would scorn.>>

<< One hog we found had the hugest flowers I’d ever seen: that’s E‘s man-sized palm for scale, not my girly-paw.

<< One hog we found had the hugest flowers I’d ever seen: that’s E‘s man-sized palm for scale, not my girly-paw.

Native solitary bees buzz in and out of the cuplike blooms, sometimes invisible except for waggling stamens deep in the throat of the flowers. Click on the photo below to see a bee-butt poking upward, right next to the apple-green pistil, which hasn’t opened fully into its star-shaped ærial panoply. You can also see the formidable armory of spines on the fleshy, water-hoarding stems. Even javelina are discouraged by them, although I’ve seen otherwise imposing boar javelinas with lips daintily reddened by the petals of the flowers of a “claret cup” hedgehog cactus. This petal-snacking would be considered hog-on-hog predation, except that neither javelina nor hedgehogs are actual pigs.

right next to the apple-green pistil, which hasn’t opened fully into its star-shaped ærial panoply. You can also see the formidable armory of spines on the fleshy, water-hoarding stems. Even javelina are discouraged by them, although I’ve seen otherwise imposing boar javelinas with lips daintily reddened by the petals of the flowers of a “claret cup” hedgehog cactus. This petal-snacking would be considered hog-on-hog predation, except that neither javelina nor hedgehogs are actual pigs.

down-wind on a gale at the South Jetty at Fort Stevens State Park.

down-wind on a gale at the South Jetty at Fort Stevens State Park.