We go from desert Gryphons to desert Chimaeras — of course, not real chimaeras, in either the mythological or the genetic sense. I’m talking about planting desert perennials in clumps, so that with maturity comes an exciting mixed-plant combo that combats the tedious “Plug-a-plant” school of xeric landscaping we see so much of here in Phoenix and other desert cities.

Many yards and businesses suffer from this dull technique of desert landscaping: start with a flat space topdressed with gravel, plug in a desert perennial, like a Rain Sage (AKA Cenizo, Leucophyllum spp.) or Brittlebush (Encelia farinosa), then plug in another one 20 feet away, and another, and another, ad nauseum, like the last pieces on a chessboard chasing each other around. Worse still, these tough plants are then often abused by being trimmed into lollipops or wonky cubes. To my eyes, it’s a sterile and unnatural look that people latch onto for two simple reasons: it looks tidy, and it’s considered “easy-care.” These are not bad things. But what some would call “tidy” I would call “severe”. And the “Plug-a-plant” plan isn’t really easy care: Because although the plants selected are often natives, both the space between them and the pruning-up of their foliage allows sunlight and heat to reach the soil and even the base of the plant, which means they usually require supplemental watering to thrive.

both the space between them and the pruning-up of their foliage allows sunlight and heat to reach the soil and even the base of the plant, which means they usually require supplemental watering to thrive.

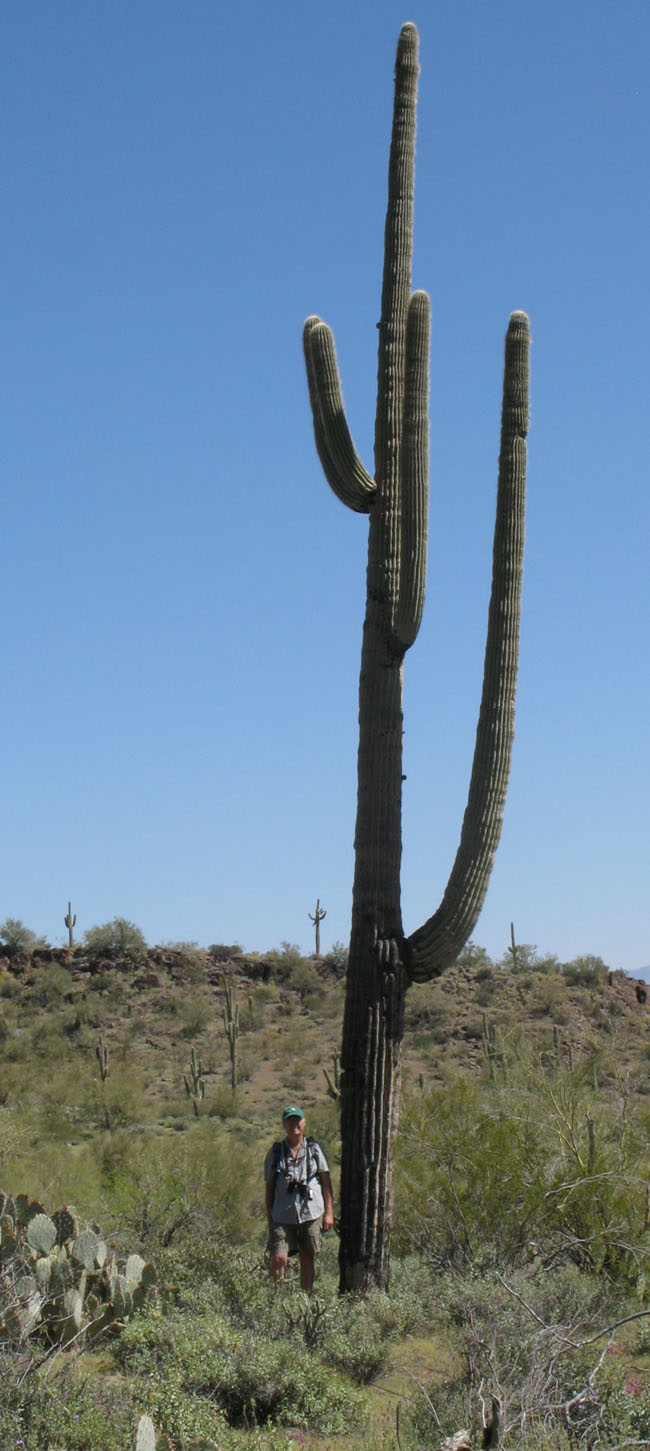

In the Real Desert, plants don’t grow that way: in all but the most parched deserts, plants clump, intertwining and growing up through each other. That way, they shade each other’s roots, and provide sun-protection for young plants, and wind protection in an open landscape. This is such an advantage that to some degree it outweighs the disadvantage of competition among close neighbors for resources like water and nutrients. The classic example is a saguaro growing up under a “nurse tree” like a Palo Verde or Ironwood: the tree shelters the young cactus until it’s tough enough to survive the hot sun and drying wind on its own, when it comes up through the branches of the nurse tree. Many desert cactus, like Graham’s Nipple Cactus (Mammillaria grahamii) struggle in the full sun of the low desert, and grow their entire lives under the eaves of perennials like bursage and brittlebush.

An excellent example of how nature and gardeners differ is where each grows the excellent Sonoran twiggy shrub Chuparosa (Justicia californica). Once established, it’s a low-care plant used along highways and in yards and commercial plantings, usually planted alone in full sun and lightly irrigated, where it takes on a robust cage-like growth pattern of its green, photo-synthesizing stems that in season end with lots of small red, hummer-attracting tubular flowers. Very nice. So imagine my surprise when I first saw it growing in the  wild on a hike in the McDowell Mountains: it was clambering up inside palo verdes, ocotillo, and other shrubs and trees almost like a vine with shaded roots, its stems growing upward to the sun and offering its blooms to pollinators several feet in the air, often inside the shady branches of its support plant.

wild on a hike in the McDowell Mountains: it was clambering up inside palo verdes, ocotillo, and other shrubs and trees almost like a vine with shaded roots, its stems growing upward to the sun and offering its blooms to pollinators several feet in the air, often inside the shady branches of its support plant.

Once I observed this, there was no going back: Chuparosas went in under many of our mesquite trees, and intertwined with ocotillo, wolfberry (Lycium spp.), Ruellia (R. peninsularis) and the Chihuahuan native, Woolly butterfly bush (Buddleyia marrubifolia), Pink fairy duster (Calliandra eriophylla) and even red Chuparosa with the yellow-blooming variety. When everyone’s in bloom it’s a mosaic of color. Here are some photos, taken just this week in our yard. Be sure to click on each to enlarge.

Above left: blooming chuparosa, up a mesquite. When the chup is young, it’s protected by the light shade of the mesquite, but it quickly grows up to the light, where it blooms.

Next, right: a Pink fairy duster, red chuparosa, and a non-native senna.

Left, a yellow variety of Chuparosa growing entwined with a Ruellia.

You can also plant plants next to one another so they grow like different-looking parts of the same plant. Here’s a blooming Pink fairy duster twinned with a Triangle-leafed bursage, also in bloom so that it looks like a half-green-half-pink plant:

I suppose I would have to admit that, like plug-a-plant, this style of desert landscaping might not be to everyone’s taste, as it does give the impression of lots of rambling natives and spots of mixed color. But allowing your plants to follow more natural growth-habits does have the advantage of cutting down on or even eliminating supplementary watering, and NO PRUNING except in cases of particularly rambunctious growers.

All photos A. Shock.

One bit of advice for desert gardeners: don’t forget to water newly transplanted plants for a couple or even three years, until they’re well established. Plants grown in nurseries for sale in containers are grown very wet, even desert varieties. This can actually shorten their lives as it it can hasten them to bloom, and it also makes them water-needy in your garden. Even desert natives need extra water to make the transition from pots to landscape. Seedlings are another story: consider growing desert natives from seed — they establish rapidly without much extra water, adjusting their size and growth rate to what’s availble to them naturally. So don’t despair if your gallon-sized Penstemon only lasts one season — as long as it flowers, you’ll have drought-hardy seedlings next year.

Another tip for low-desert gardeners is regarding the ever-present Creosote bush, or “Greasewood” (Larrea tridentata). It’s one of the toughest, most drought-hardy desert shrubs around (and smells great in the rain), but it’s got a chemical defense system that “discourages” (i.e. kills) some other plants, or inhibits seed germination. (In fact, this plant is the exception that proves the rule: it’s got this defense to keep shade-sharing and water-sucking free-loaders away.) So, if you’re planting under Creosotes, make sure you’re putting in creosote-tolerant species. For instance, we’ve had luck with Christmas cholla (Cylindropuntia lepticaulus), but less luck getting Chuparosa started under creosote.

For a few days I’ve been whiffing a whiff, which has caused me to search for the dead mouse in my studio.

For a few days I’ve been whiffing a whiff, which has caused me to search for the dead mouse in my studio.