Cucumbers don’t usually have scales

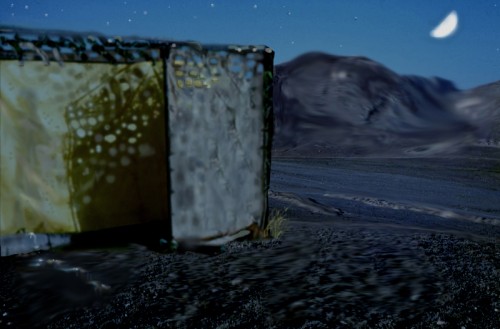

<< Here are my next-door neighbor’s cucumber plants, with a snake napping amidst them. The neighbor noticed it when he was rummaging around in these leaves looking for cukes for dinner. I happened to be in our backyard, and saw him and his wife standing just on the other side of our shared block wall, and went over to see what they were looking at.

<< Here are my next-door neighbor’s cucumber plants, with a snake napping amidst them. The neighbor noticed it when he was rummaging around in these leaves looking for cukes for dinner. I happened to be in our backyard, and saw him and his wife standing just on the other side of our shared block wall, and went over to see what they were looking at.

“A gopher snake.”

The wall is six feet tall, and I can’t see over it. So I asked him if he would mind snapping a shot of their snake with my cell phone. He obliged, and handed the phone back to me. As I walked away, I checked to see if the picture was in focus; cell-phone cameras are capricious that way. Nope, in fine focus (photo above).

“Umm, Dane? I don’t think that’s a gopher snake.” I fetched a flimsy plastic chair to stand on, and peered over the wall straight down onto the comfy animal. It was a beautiful Western diamondback rattlesnake, curled in the ‘cukes, snoozing and digesting its latest meal. I could see the sun glinting off of its rattle, concealed deep in the center of its keely-scaled coils. >>

glinting off of its rattle, concealed deep in the center of its keely-scaled coils. >>

The Fire Department was called, and a re-location made. The Scottsdale FD is equipped for reptile removal. They only take snakes from settings urban enough that the reptile might be considered “out of place” — if you live in the foothills, or on the edge of open desert, they will tell you your snake isn’t a suitable candidate for removal, because it’s at home in your yard. But in our mixed suburban-desert zone they came  for the neighbor’s rattler, in a huge, danger-green fire engine — three strapping, uniformed Firemen with their names embroidered on their dark blue uniforms (why would a desert community make their public safety officers wear dark blue in the desert sun?) redolent of calm and expertise. The guy with the snake-tongs had on shorts. The entire scene was calm. No one was horrified, or panicked, or officious. If it hadn’t been for the fact that the neighbors have a 14-month old grand-daughter and an overly-mouthy not-too-bright black lab

for the neighbor’s rattler, in a huge, danger-green fire engine — three strapping, uniformed Firemen with their names embroidered on their dark blue uniforms (why would a desert community make their public safety officers wear dark blue in the desert sun?) redolent of calm and expertise. The guy with the snake-tongs had on shorts. The entire scene was calm. No one was horrified, or panicked, or officious. If it hadn’t been for the fact that the neighbors have a 14-month old grand-daughter and an overly-mouthy not-too-bright black lab , I think we all would have been happy to let the snake stay put and take in more roof-rats. There’s plenty to go around, along with the pocket mice, cottontails and those tomato-thieving rock squirrels who disemboweled Shelby’s patio furniture cushions to line their nest in our attic with. All of us would have traded the snake for the rodents, any day. But… the grand-toddler… So unless there are more rattlers, the gopher snakes will have to take care of the rats.

, I think we all would have been happy to let the snake stay put and take in more roof-rats. There’s plenty to go around, along with the pocket mice, cottontails and those tomato-thieving rock squirrels who disemboweled Shelby’s patio furniture cushions to line their nest in our attic with. All of us would have traded the snake for the rodents, any day. But… the grand-toddler… So unless there are more rattlers, the gopher snakes will have to take care of the rats.

The capture was uneventful; the snake’s belly was  bulging from recent feeding, and it only rattled a little. It was taken away along with repeated assurances it was destined for safe relocation (I chose to believe the nice officers). The fireman with the snake even paused to let us take photos — my neighbor had his video cam and I was still hanging over the wall with my camera. The rattler, which was only about three feet long, just looked pissed off.

bulging from recent feeding, and it only rattled a little. It was taken away along with repeated assurances it was destined for safe relocation (I chose to believe the nice officers). The fireman with the snake even paused to let us take photos — my neighbor had his video cam and I was still hanging over the wall with my camera. The rattler, which was only about three feet long, just looked pissed off.

The folks next door have lived in their house since the 1970s, and they’ve never seen a rattlesnake around here in all that time. But the Army National Guard just paved over a generous chunk of their desert two blocks south, and the city has an on-going streets improvement project a couple of blocks in the other direction. I’ve seen more coyotes in the past few months  than in the rest of the time we’ve lived here, including one IN our (totally walled) yard. We suspect this habitat loss and upset is forcing critters there to move into our streets.

than in the rest of the time we’ve lived here, including one IN our (totally walled) yard. We suspect this habitat loss and upset is forcing critters there to move into our streets.

Not infrequently the topic of snakes comes up among the folks who live here, and I often mention what a good idea it is to not kill snakes because they eat rodents (we’re in a part of the Phoenix area plagued with non-native roofrats). One of the reassuring things I tell people is, “Anyway, all the snakes around here are non-venomous — we don’t have rattlers any more in this area.” Oops. Also, I’ll be carrying a flashlight when I go out into the yard at night, now. There hasn’t really been a need: the raccoons are scrappy, but they’re not venomous.

And it’s still not a good idea to kill snakes.

(All photos A.Shock; click to enlarge)

Allison does not consider herself a wildlife artist,

but an observer who takes notes in clay.

Allison does not consider herself a wildlife artist,

but an observer who takes notes in clay.