What happened at Beit Bat Ya’anah: part 14

UPDATE: I’ve just made it easier to navigate between episodes of What Happened at Beit Bat Ya’anah. Now at the beginning of each new episode there are links to previous installments: one to the immediately previous episode, and one to the very first episode. In addition, there’s a link at the end of each episode to click on so that you can  read the very next one in the series, if it’s been posted. You can always click on the Beit Bat Y a’anah category in the left-hand sidebar, but it’s a little awkward to navigate forwards through time from the bottom up now that the series is stretching into more episodes. (My apologies to those readers whose RSS feeds may have been bombed with updates this morning as a result of the changes, although I hope it’s not many of you!)

read the very next one in the series, if it’s been posted. You can always click on the Beit Bat Y a’anah category in the left-hand sidebar, but it’s a little awkward to navigate forwards through time from the bottom up now that the series is stretching into more episodes. (My apologies to those readers whose RSS feeds may have been bombed with updates this morning as a result of the changes, although I hope it’s not many of you!)

This is the fourteenth installment of the series. The following links will take you to the last episode before this one, and the very first episode:

Read Part 13 ………………………………………………………………….For new readers: Read Part 1

Previously:

Having taken a brief side-trip to observe the volatile and imperious Avsa Szeringka at home in her Institute near London, we rejoin the excavation at Beit Bat Ya’anah (BBY), where Professor Wayfarer, still frustrated in her efforts to observe Szeringka’s graduate student, is once again considering whether or not to extend her stay at the remote, unpromising site in the Negev desert. To her own surprise, every fact she learns about BBY – such as its lack of ancient burials and its brief stint as an ostrich ranch – makes her more curious about the process of excavation, the many unanswered questions about the place, and its residents, both past and present.

Meanwhile back at the ranch: earthmoving

Einer Wayfarer had never been among people who knew or cared so much about dirt.

As a well-established and respected figure in her recondite field, the professor had at her disposal considerable quantities of highly specialized and well-integrated philological, linguistic, and literary knowledge. But after eight days assisting the excavation team at Beit Bat Ya’anah, the professor had acquired a range of experience which she’d never  expected to accrue in her lifetime – most of it concerning dirt, the objects people lost or left in it, and the best tools for moving large amounts of it quickly but carefully.

expected to accrue in her lifetime – most of it concerning dirt, the objects people lost or left in it, and the best tools for moving large amounts of it quickly but carefully.

During the past week Wayfarer had helped shift a lot of dirt. Though exempted by seniority from some of the more strenuous tasks, she’d watched the younger folk swing a pick to loosen the hard soil, then use the sturdy hoe called a turiyah to fill a guffah or a dli to pass to someone topside to push to the soil dump in a wheelbarrow.

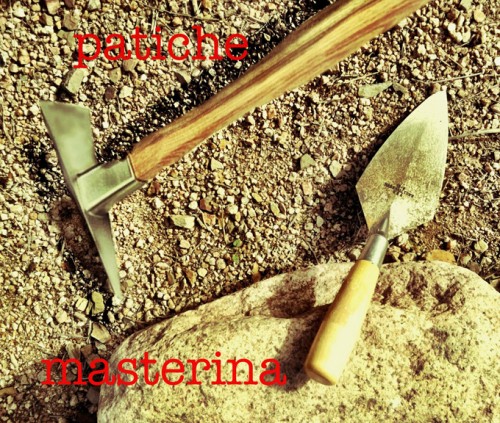

Wayfarer herself had shake-sieved cubic feet of stony soil for infinitesimal clues to lives from distant times. She learned to use a masterina to work around an object in situ, to level surfaces, and to remove small amounts of dirt. She observed that Marshalltown was the trowel of choice among the Americans, whereas the Israelis and Aussies preferred no-name brands from local building suppliers, with the result that unfortunate young Eric took constant flak from both sides about the British-made WHS 4” pointing trowel his parents had mail-ordered specially from a posh archæological outfitter in London.

British-made WHS 4” pointing trowel his parents had mail-ordered specially from a posh archæological outfitter in London.

Thanks to Rory’s instruction, Wayfarer was becoming handy with a patiche and could use one to polish a balk without undercutting, to reveal a vertical stratigraphic witness to the sharp interpretive eyes of the senior staff. Zvia showed the professor the difference between a packed-dirt floor horizon and an organic-rich kitchen midden or an ashy interior hearth feature, and how it was possible to articulate a wall with acceptable statistical probability from a poor showing of three or four rough-hewn blocks or even sketchier field-cobbles. Wayfarer learned that a pisé wall was different than a mud brick wall, and that both decayed by dissolving from the bottom up between the corners, as opposed to stone walls which dilapidated from the top down. She learned that stone tools weren’t necessarily a sign of great antiquity: handy rocks were used in every era for many reasons, and ancient tools were often kept and used through centuries, their presence in a stratum providing no more than a terminus post quem. Lior had helped her construct a rudimentary but functional pottery typography in her head, and she could sort with some accuracy the local chalcolithic ceramics from Bronze Age. She was surprised to learn that there were shells from both the Mediterranean and the Red Sea found at the land-locked site, and that it was necessary not only to identify and quantify them, but also to field-screen them for signs of secondary usage by looking for signs of edge wear or drill holes. At the end of the day when the sun angled low, the professor had climbed back onto the hill to help anchor the ladder for Mikke who, with her billowing gypsy skirt tucked into her waistband shirwal-style, cantilevered riskily from upper rungs in order to shoot down onto squares with newly uncovered features or strata; and Wayfarer had held the stadium rod for Shams’s precise transit surveys of the growing length of meager, mainly Middle Bronze Age walls visible on the ridge.

The professor had quickly realized that what had at first appeared to her to be a grubby collection of callow, work-worn drones was actually a field-hardened team with specialized skills carrying out a project where success was neither guaranteed nor likely to be spectacular, and failure was irreversible: archaeology was controlled destruction – once a feature, locus, or a soil horizon was removed, it was gone beyond recovery. In an excavation so devoid of significant cultural artifacts, the soil and rocks they were uncovering were everything: even a lowly trowel-wielding novice such as herself had to  pay close attention in order to avoid committing irreparable errors of excavation like digging through a foundation trench or clearing rubble that turned out to be a casually paved floor.

pay close attention in order to avoid committing irreparable errors of excavation like digging through a foundation trench or clearing rubble that turned out to be a casually paved floor.

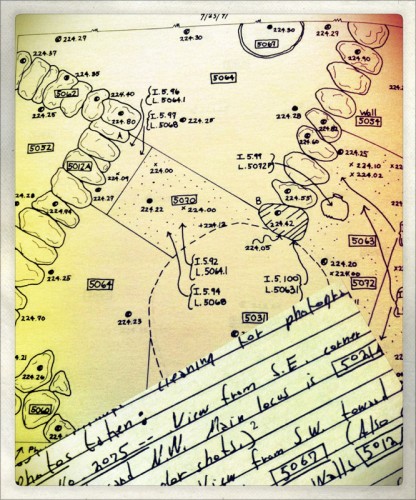

The only thing that mitigated this destruction was meticulous record-keeping – written, quantified, measured, sketched, and photographic – since it preserved information for interpretation and, inevitably, later re-interpretation. The schedule was unvarying: digging on the Hill in the morning and recording in the lab in the evening, but the interpretation was constant. The staff spent endless hours on site, in the lab, and around the dinner table in earnest and democratic discussion of minute changes in soil, the relative stratigraphy between areas, and the chronological relationships of excavated features, levels, and loci.

Watching the senior staff at work, Wayfarer began to comprehend the blend of informed observation, technical expertise, bare-knuckled logistics and personnel management skills that a successful dig demanded. She saw that BBY’s directors Chayes and Rankle – whatever she might think of their contrasting personal styles – were each experts in their own ways, both indispensable to a smooth field campaign. Keeping a sharp eye was a question not only of archæological necessity, but sometimes of fundamental safety, as Wilson Rankle reminded them all in a harsh public scolding of young Eric. The director had discovered an undercut 2 meter balk in Area C which he proclaimed to be “an unmitigated catastrophe waiting to happen, Eric, with your damn name writ large upon it.”

In addition to the arcane secrets of managing dirt, the practical skills of desert life were now Wayfarer’s too. She’d learned the importance of drinking water before she was thirsty and of never picking up sun-heated tools by the metal parts. During breaks she learned to value even the smallest scrap of shade, and was known to take refuge in big Rory Zohn’s substantial umbra despite the olfactory risk. In camp, she knew to check her shoes each morning for scorpions and centipedes, to always carry a flashlight after dark, and to keep her distance from the flat rock at the downhill end of the communal sinks because of the yellow-jackets during the day, and at night, too, since a small viper had taken up residence underneath to ambush tiny scurrying mammals attracted by the sink’s moist outflow. Less usefully (although more likely to impress her students back in Lassiter), because of the international nature of the crew and the earthy quality of conversation in the lab in the evenings, the professor now knew how to exhort someone to go screw themselves in four new languages including – thanks to Shams – both Urdu and Strine.

But she hadn’t planned on staying more than a few extra days, and that time was up. Originally, Wayfarer had postponed her departure on Avsa’s behalf, but now, a little more than a week later, there were other reasons the professor was considering extending her stay at “Two-Bit Yod” (as Rory had semi-affectionately subverted the Hebrew letters Beit-Beit-Yod of the site-abbreviation, written on every find tag and locus card). One main reason was purely altruistic: this close to the end of the season, any assistance, even rookie, was helpful. The site was chronically short staffed due to the Lebanese conflict: the Israelis kept having to report for brief stints of discreet military service. Yoav the ethnobotanist was the latest to disappear – early one morning Wayfarer saw him sling his kitbeg into the back of the site Landrover where it settled with the somber clank of gunmetal. Chayes drove him out to the highway to hitch a ride to Be’er Sheva – but later at tea, no one said anything about this departure. Wayfarer thought it likely that Aman, Israeli military intelligence, recruited as heavily among archeologists as other governments had during conflicts in Europe and the Middle East – in retrospect, she suspected that Chayes’s earlier absence had had more to do with Aman than with his son’s spider bite.

So, despite the heat, discomfort, and insect life, Wayfarer’s mind was made up. She asked Amit if an extra pair of hands would be welcome; he smiled and clapped her shoulder, saying he’d let Moshe know. Rankle she merely informed that she was staying, and received a pessimistic response doubting whether the water would last. It only remained for her to ask the Aussies, who were headed out to Eilat for weekend leave, to pick up some things for her: a bottle of Hawaii shampoo, a sack of clothes pins (her colorful plastic ones in a clever mesh bag had gone missing off of the line), a bottle of red, and she’d be good for another week, until the end of the season.

Practicalities being satisfactorily settled, the professor spared some attention to the lingering question of Avsa’s uncooperative protégé, who continued to avoid her like a student with a delinquent thesis chapter. But she didn’t give him much thought. When it came to coaxing results out of students she knew more than one way to  skin a cat.

skin a cat.

No; Wayfarer was definitely not yet ready to leave. By Saturday night, or Sunday morning at the latest, she should have a bottle of wine to look forward to. And ever since Amit had mentioned them, she’d been dreaming about herds of strong-toed ostriches wandering freely among the jumbled rocks of the Upper Wadi, their big liquid eyes peering deep into her resting mind.