Cranky Owlet has elevated…

…crankiness to an artform.

Days are getting short until Three Star Owl‘s third appearance at Southwest Wings Birding and Nature Festival, and I’m in a groove, making pieces for the event. As posted, I’ve been making mugs, and also owls. Lots of owls. Even more owls than usual.

So recently I turned to the hairy side of Sonoran fauna, and have been doing Javelinas. Javelina items are popular with Three Star Owl clients, both Arizonans and visitors to the desert. Interestingly, it’s often people who have lived their lives in the less urban areas of AZ who are NOT fans of the rooting, tusk-bearing mammal: they may have grown up thinking of them as pesky neighbors, and are weary of battling them over landscaping, gardens, and garbage, or are tired of sewing up the hound.

But in general, javelinas have lots of fans. I was thrilled when a herd temporarily moved into our neighborhood a few years ago. They were flooded out of their usual habitat during a rainy year when the Salt River swamped the Goodding’s willow woods growing up in its channelized banks. They did a bit of damage in yards, including ours, but I also still remember the thrill of hearing clicking sounds coming up the street, and looking up to see a mama with two quite young piglets following her!

They were flooded out of their usual habitat during a rainy year when the Salt River swamped the Goodding’s willow woods growing up in its channelized banks. They did a bit of damage in yards, including ours, but I also still remember the thrill of hearing clicking sounds coming up the street, and looking up to see a mama with two quite young piglets following her!

Javelinas are not true pigs: they are pig-like mammals in the peccary family, Tayassuidae, and have a New World origin as opposed to pigs and swine, family Suidae, which originated in the Old World. Our javelinas are also called Collared Peccaries, and live in a wide geographical range and a variety of habitats in the arid Southwestern U.S. There are three other species of peccary in the Americas, which live throughout Central and South America: White-lipped, Chacoan, and Giant Peccaries.

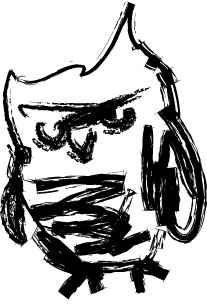

Three Star Owl will be offering Javelina candle-holders and salt and pepper shakers for your table. Here’s a colored pencil drawing of a pair of shakers in progress. It’s not the drawing that’s “unfinished” it’s the clay objects, which are in two stages of completion, still in wet clay. One is modeled and textured, the other not yet detailed or textured. The shaker holes are the nostrils at the end of their snouts, and each one is re-fillable through neat rubber plugs in their bellies.

Three Star Owl will be offering Javelina candle-holders and salt and pepper shakers for your table. Here’s a colored pencil drawing of a pair of shakers in progress. It’s not the drawing that’s “unfinished” it’s the clay objects, which are in two stages of completion, still in wet clay. One is modeled and textured, the other not yet detailed or textured. The shaker holes are the nostrils at the end of their snouts, and each one is re-fillable through neat rubber plugs in their bellies.

And here is a larger candle-holder, completed. The salt and peppers will have the same coloration, matte slips and oxides, with a little sparkle in the eye.

And here is a larger candle-holder, completed. The salt and peppers will have the same coloration, matte slips and oxides, with a little sparkle in the eye.

(Photos: top, javelina dirt-napping at the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum, E.Shock; javelina in our front garden, munching spring wildflowers, A.Shock; colored pencil sketch on recycled, speckled paper, A.Shock; Three Star Owl javelina candle holder, A.Shock)

“Paean to the Short-all” (India ink and watercolor sketch, 6×9″, A.Shock)

One crabby technical addition: note the bleeding that occurred in the sepia ink lines adjacent to washes in the drawing. This happened after adding the watercolor washes, after an hour of ink-drying time. So, if you’re using Higgins “waterproof” sepia drawing ink, note that it doesn’t appear to be entirely waterproof, despite what it says on the bottle. Perhaps more drying time? Actually, the effect if you were doing an ink wash could be nice — a pleasant sanguine fuzziness — but not so much when you’re looking for a clean line to contain tinted areas. Especially around the lettering…

In our area, the first Gambel’s quail chicks of the year usually start showing up in early May, clustered around their parents under the mesquite trees in the yard, pecking expertly at the ground like the precocial youngsters they are. This year, since we weren’t around then, we missed the “nebula phase” of their development — when they’re so small and move so fast that it’s hard to count them: a streaky brown cloud of down orbiting the adults like electrons, running everywhere because their legs are so short.

youngsters they are. This year, since we weren’t around then, we missed the “nebula phase” of their development — when they’re so small and move so fast that it’s hard to count them: a streaky brown cloud of down orbiting the adults like electrons, running everywhere because their legs are so short.

Now that we’re back, the feeders are full again, and the parents are bringing their broods around. For the past two days there’s been a family of six cleaning up nyger thistle that the frenzy of fressing finches let fall from the front mesquite feeder: two adult quail and four chicks. The chicks are still quite young, but no longer downy — adolescent really, and they’re beginning to get little nubs on their foreheads where their topknots will grow in. They are still cryptically colored buffy-streaky so that they’re nearly invisible against the soil in the dappled sunlight let through by the mesquite’s tiny compound leaflets. Papa usually stands watch as the family feeds, which they do at a more leisurely pace than when it’s the adults alone. This may be a clutch incubated in the spiky tangle of our fan-palm, where a hen successfully raised a brood of 9 last year.

Normally I’d snap a photo of the family scene above. But because I can’t get a decent picture through the reflection-hazed windows looking out onto the feeders (I’ve tried!), and going outside would start the whole shebang to flee, I thought I’d sketch from life (above). I’m just finding my way around watercolors again after a very long absence, and haven’t managed to loosen up as much as I’d like — at this point, I seem to produce tinted drawings, rather than acheiving a freer painting style. One reason for that is that it’s such a different process than capturing “birdness” in the broad, unblended swatches of opaque glaze color, which is what I normally do, as in this Three Star Owl male Gambel’s quail wall tile pictured to the right.

Normally I’d snap a photo of the family scene above. But because I can’t get a decent picture through the reflection-hazed windows looking out onto the feeders (I’ve tried!), and going outside would start the whole shebang to flee, I thought I’d sketch from life (above). I’m just finding my way around watercolors again after a very long absence, and haven’t managed to loosen up as much as I’d like — at this point, I seem to produce tinted drawings, rather than acheiving a freer painting style. One reason for that is that it’s such a different process than capturing “birdness” in the broad, unblended swatches of opaque glaze color, which is what I normally do, as in this Three Star Owl male Gambel’s quail wall tile pictured to the right.

The past three days I’ve been immersed in clay. Sounds muddy, but what I mean is, of course, NCECA: demos, tools, galleries, other clay artists, techniques, long-time friends from St. Louis, Metro Light Rail, even a little shopping, and downtown Phoenix: all those things compressed into a fairly short amount of time, in three long but stimulating days.

The Potters as Sculptors, Sculptors as Potters show was fabulous, and folks who made the trip out to Mesa Community College saw a broad yet focused themed show that added a lot to the exhibition experience at NCECA. The room was light and spacious, and packed full of pairs of pieces showing the range in various artists’ work, and how they deal with the duality of making both vessels and sculpture. (Here’s a shot looking into the gallery. My pieces, Stacked Toad Teapot Effigy and Venomosity are the two objects nearest to the camera.) Saint Louis clay artist James Ibur finessed an adroit and thoughtful piece of curation in organizing this show, as well as doing a lot of hard work.

The bulk of the event was deep in the bowels of the Phoenix Convention Center, and almost all of it was nearly simultaneous. To make the most of NCECA you have to be good at time management and willing to switch gears mid-stream. I watched a Korean Onggi potter make really big pots in the traditional style. He made the coil of beige clay at his foot by stretching 25 pounds of clay all at once on the floor like a giant taffy loop. He would then rest the coil on his shoulder while feeding it onto the top of the pot. He said at home each potter made 30 of these in a day! That’s a lot of kim-che storage — and a lot of clay.

The bulk of the event was deep in the bowels of the Phoenix Convention Center, and almost all of it was nearly simultaneous. To make the most of NCECA you have to be good at time management and willing to switch gears mid-stream. I watched a Korean Onggi potter make really big pots in the traditional style. He made the coil of beige clay at his foot by stretching 25 pounds of clay all at once on the floor like a giant taffy loop. He would then rest the coil on his shoulder while feeding it onto the top of the pot. He said at home each potter made 30 of these in a day! That’s a lot of kim-che storage — and a lot of clay.

There were also on-site installations constructed during the course of the meeting, like this one of a California gray whale made of clay packed onto slat-armature. The mini-whale in red clay on the boxes is the artist’s maquette, and you can just see a few slats still un-clayed at the far left edge of the photo.

the course of the meeting, like this one of a California gray whale made of clay packed onto slat-armature. The mini-whale in red clay on the boxes is the artist’s maquette, and you can just see a few slats still un-clayed at the far left edge of the photo.

The NCECA exhibitors’ hall is also a great place to shop for the latest tool, equipment, or silly clay tee-shirt (“Throwing my life away” “Tee-shirt for my clay body”, etc). But the best tool ideas I picked up were being used by the demonstrators, like this one used by the Korean potter above: it’s a wooden hand-held anvil used on the inside of the pot while the outside is beaten with a wooden paddle. This thins the clay and compresses it, making the walls of the pot stronger and reinforcing the joins between the coils. Wood tends to stick to wet clay, so the face of the tool has been textured so it releases more easily. It also leaves a great texture behind. But, it wasn’t available for sale in the exhibition hall, so if you want one, you’ll have to make it yourself (I’ve always used a river-cobble as an anvil).

it’s a wooden hand-held anvil used on the inside of the pot while the outside is beaten with a wooden paddle. This thins the clay and compresses it, making the walls of the pot stronger and reinforcing the joins between the coils. Wood tends to stick to wet clay, so the face of the tool has been textured so it releases more easily. It also leaves a great texture behind. But, it wasn’t available for sale in the exhibition hall, so if you want one, you’ll have to make it yourself (I’ve always used a river-cobble as an anvil).

I mentioned shopping, and that’s because much of the art on display was for sale. Probably the most notorious selling frenzy at the conference is the Cup Benefit sale, where artists donate cups for a sale, the proceeds of which go to art scholarships. The cups are displayed for two days, then, on the third day, they throw open the doors and let people in a few at a time to shop. The cups are donated by lots of artists, from plain folk to rock-star potters — the most famous names in the business — so the line to get in is long, and people arrive early. By early I mean 4.30am! Although I had my eye on a specacular piece with burrowing owls stencilled on it, it was long gone by the time I got in. So I contented myself with two appealling cups by potters unknown to me — oddly, both named Reilly/Riley.

There’s a property of owls I call “Half-Dome Head.” It’s a shape that’s noticeable in the profile of all owls, particularly the larger ones. The Barred Owl to the right is exhibiting major Half-Dome Head. If Half-Dome Head can be achieved when making owls in clay, the resulting effigies will be Especially Owly.

There’s a property of owls I call “Half-Dome Head.” It’s a shape that’s noticeable in the profile of all owls, particularly the larger ones. The Barred Owl to the right is exhibiting major Half-Dome Head. If Half-Dome Head can be achieved when making owls in clay, the resulting effigies will be Especially Owly.

The name derives from the famous granitic dome formation, Half Dome, in Yosemite Valley, California, which bears an obvious resemblance to an owl’s head in profile. The geologic Half Dome is forming largely by weathering: eons of sheet-exfoliation on the fragmented face of an exposed granodioritic batholith gave it the shape we see today. (Appropriately, one of the most Half-Dome-Headed owls ever, the regal Great Gray Owl, is an uncommon resident of Yosemite Valley, see photo below: the color and texture even match).

In owls, the “Half-Dome Head” effect arises from the front of the Owl’s head (in other words its face, to use the technical term) being shaped like a radar dish, to be efficient at gathering sensory input — in other words, light and sound. But take away the feathers and an owl’s cranium is shaped pretty much like a hawk’s, or even a chicken’s skull (check out these images). An owl is after all a bird, albeit a fairly specialized one, so it’s built like a bird. The forward-oriented flat face that we humans find so fascinating (probably for anthropocentric reasons) is due more to posture and feather-arrangement than underlying skeletal structure: the owl generally holds its bill slightly downward rather than forward like other birds. This gives prominence to the distinctive “facial disc” — the specialized array of radar-dish-like plumage around an owl’s eyes and ears — and positions it so it functions optimally.

The owl’s Facial Disc is a precise specialization for nocturnal hunters who require every available bit of light and sound directed into their sensory apparatus to ensure the highest possible success rate while hunting. Several features of the facial disc are noticeable: short flat-lying feathers sweep away from the eyes and “cheeks” so as not to impede forward vision; stiff vertically-arranged feathers edging the facial disc help funnel sound into the ear openings, which are asymetrically arranged on either side of the face behind the eye to create aural parallax (and are nowhere near the cranial tufts we commonly call “ears”); and rictal bristles (“whiskers”), which are specialized sensitive filamental feathers on either side of the gape (the flexible corners of the mouth which allow the beak to open and close), that enable the owl to perform preening and feeding activities — including the feeding of owlets — by feel, since their large eyes are immovable in the skull and so can’t focus efficiently at very close ranges.

But that’s just the flat front of the “Half-Dome”: the round back, the helmet-shaped fullness of feathers on the back of an owl’s head also transmits owliness to our perception. This is also due to the owl’s skeletal configuration: the bird’s upright posture is possible because its skull is joined to a nearly vertical spine. Most birds’ backs go off at a more or less right angle to their necks (think of a dove), somewhat shortening the curve at the back of the head. But the feathers on the back of an owl’s head arc smoothly down to the back, which continues downward steeply. The photo above shows Half-Dome head creating Owliness in an MLO (Moderately Large Owl) I’m currently working on for a client.

Photos: from top to bottom: IBO barred owl, A.Shock; Half Dome Yosemite, Carroll Ann Hodges, USGS; Great Gray owl, Canada (Sorry; don’t know who to credit this photo to); Three Star Owl “eared” owl effigy in progress, A.Shock. And finally, a Gratuitous Cranky Owlet chillin’ with the Big Boys…

As I mentioned previously, there are two pieces of mine in the NCECA “Potters as Sculptors; Sculptors as Potters” show currently up at Mesa Community College (see the Three Star Owl Events page for details). One of them is the long-evolving “Toadstack” (the other is Venomosity which can currently be viewed on the Home page.) As promised, here is the entire Toadstack story in pictures, culminating in the final state of the piece. They go from L to R and Top to Bottom; don’t forget you can click on an image to enlarge it:

and the finished piece, Stacked Toad Teapot Effigy (Toadlier than Teapotly):

This show is associated with the annual NCECA (National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts) Convention, which opens in town tomorrow (Wed 8 April). From now until Saturday, Phoenix will be popping with potters, sculptors, and ceramic arts educators. The downtown Phoenix Convention Center is the main venue, where the discussions, demos, lectures, and exhibitors will be located. There’s a fee to attend that part of the conference, but there are many many galleries, museums and other display venues which have shows up featuring the work of both nationally known and local clay artists, and these shows are FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC.

So if you like looking at the broad range of contemporary ceramic artwork and what’s being made in America today in clay, check out the NCECA website for lists of and maps to the concurrent shows and outlying venues which are all over the metro area. Principal show clusters are located in Tempe, in and around the ASU Campus; Mesa, at both the Community College and the Arts Center; downtown Phoenix in the hotels around the Convention Center; and Scottsdale, in the Old Town Arts District, a fun and stimulating place to visit anyway. It’s a great time in Phoenix to Get Out and See Art.

The Anna’s Hummingbird Hen’s behavior has mystified me for the last few days. What I see when the Hen is gone: an empty nest, no nestling activity (after that first exciting view). Then when the Hen returns, she immediately sits tight; no feeding. Wouldn’t you expect her to return and feed nestlings, if there were any? And yet there’s no doubt there is/are nestlings in the Nid; I saw it/them. Frankly, these have been anxious days for me. But, figuring the Hen knows what’s what with her Nidlings, I just hung loose and tried not to imagine an inexperienced hen sitting on the corpses of un-fed young ‘uns. Ew.

And? Then Sunday evening, a warm, calm, acacia-fragrant evening while it was still light, I looked down on the Nid from the upstairs window, and saw Fascinating Behavior. The first was a definite look at a dark, fuzzy head with a now orange-yellow bill restlessly moving in and out of sight from the depths of the Nid. This was very exciting. Then nothing for several minutes — the Hen was away for quite a while on this outing. It gave me a chance to study the inner edge of the far side of the Nid, and think how clean it was: no poop. I realized I’d never seen a hummer carrying a white fecal sac away from a nest, like many songbirds do to keep their nests clean: food in, fecal sacs out. I wondered if a nestling hummer produced a fecal sac that was just so small I’d never noticed. Just then a gray fuzzy lumpish shape appeared over the rim: a second nestling!… but, no — it has no face? What…? Then: SPLORTCH! Like a jet of ‘baccy juice from the lips of a cartoon hillbilly, a tiny projectile squirt came shooting over the rim of the nest and arced towards the ground. So that’s how it’s done! No fecal sacs here for mom to cart away, just a butt-skywards and a quick squeeze, and business has been taken care of.

The second event was the Hen returning. And, to my relief and fulfilled expectation, she perched on the edge of the nest and pointed her beak downward. Just like in the nature films, two little heads rose up to meet her, and she poked her bill down one gullet and then the other, dispensing yummy liquid Gnat-in-Nectar stew to each Nidling in turn, the bigger one going first.

To the right is a close-up of an Anna’s hummingbird stamp on a Three Star Owl “Hummingbirds of Arizona” cylindrical vessel. (Both photos: A.Shock)

No pictures of any of this excitement. I’ll try, but I’ve decided to paper over the window until fledging. It would be awful if our voyeurism, or the cats, who love to sit and “read the backyard newspaper” from this window, caused her to abandon the nest. I’ll leave a flap to peek through, like an impromptu blind, and maybe before long I’ll manage to get a photo. The best I can do is leave you with this link to someone else’s photo of exactly what I saw.