This is the third installment of a series. Click on the link at the bottom of the page to continue to the next installment. Or, click here to read from the very beginning. Previously:

“There’s half an hour until dinner. Would you like to see the object now?” After coming halfway around the world on short notice, she was being offered just half an hour of face time with the mystery object? Not damn likely. “Thanks, Wilson,” she said, “but it can wait until after dinner, I think. I’d like to chat with your staff.”

Wayfarer’s explanation

“Every museum in the world has some, imprisoned in drawers, supporting rodent traps in off-site storage lockers, hunkered down in the bottom of boxes with yellowing, silverfish- nibbled labels,” Professor Wayfarer was warming to her subject. Overhead a string of low-wattage bulbs twinkled, shedding a soft glow onto the dining tables at the dig camp. After dinner, her first night on site and against her better judgment, Wayfarer found herself explaining – more or less – why she was at Beit Bat Ya’anah.

nibbled labels,” Professor Wayfarer was warming to her subject. Overhead a string of low-wattage bulbs twinkled, shedding a soft glow onto the dining tables at the dig camp. After dinner, her first night on site and against her better judgment, Wayfarer found herself explaining – more or less – why she was at Beit Bat Ya’anah.

She was at the excavation site at Avsa Szeringka’s request. But that she was explaining why publicly was William A. Rankle’s fault: during the meal he had started in, critically, about Szeringka’s well-known professional eccentricities. In a different field, he didn’t know Avsa personally: he was just repeating hearsay, which irritated Wayfarer particularly. She felt she ought to put up some defense for a friend, even though she herself wasn’t entirely convinced of her colleague’s recent research direction. Pushing her plastic plate across the oilcloth table cover, the professor noticed that it was a cheerful printed version of the floral-on-white pattern of the eastern mediterranean faience glazes still common on clay tableware and tiles in the homes and suqs all over Israel and Lebanon, Rhodes and Cyprus, as well as excavated from ruins of the countryside. So much cultural division in this part of the world, she reflected, yet so much cultural continuity visible in the tools of everyday life.

on clay tableware and tiles in the homes and suqs all over Israel and Lebanon, Rhodes and Cyprus, as well as excavated from ruins of the countryside. So much cultural division in this part of the world, she reflected, yet so much cultural continuity visible in the tools of everyday life.

She continued, “Every day these ‘mystery objects’ are re-discovered during routine organization and clean-up of collections; they’re liberated while searching for other accessions; they arrive well-wrapped in crated bequests and cartons of anonymous donations; they’re even unearthed alongside provenanced artifacts at excavations: the so-called unsecured antiquities. Most of the time, however, they’re not even noticed. They’re the objects that no one knows what to do with, not the world-class ethno-pundits, the egg-head art history mavens, not even the archæo-techs with their analytical equipment or the archæo-geeks with their objective, impersonalized classification systems.” Not above this jab at Rankle, and never averse to holding forth in front of an audience, Wayfarer was in full spate. It was pleasant sitting under the high-starred indigo sky, her bobbed gray hair ruffled by a light breeze that was almost refreshing, with a group of attentive students listening to her over empty plates. Still no wine, but at least there were no mosquitoes, either, unlike in Lassiter.

“So, you’re trying to identify these unsecured antiquities?” asked the undergraduate, whose wasp-stung neck had sprouted a couple of painful-looking swellings.

“No, I’m an expert on neither archæology nor ancient history. My specialty is a body of literature in a language very few people outside the field have ever heard of. But a small number of my colleagues – Avsa Szeringka foremost among them – questions the likelihood that any culture would leave a substantial amount of written material behind them but no quotidian artifacts. She thinks the scattered numbers of bastard belongings – the unsecured antiquities currently unrecognized in university, museum and private collections all over the world could be ‘mined’ for candidate items, for the belongings of this crypto-culture, these hidden people.” That was sufficient; the students didn’t need to know the rest of Avsa’s controversial theories, and Rankle was already hostile enough.

Wayfarer noticed Zvi was watching the director now, whose mouth was set in an asymmetrical, skeptical line. But the big grad student with the impressive beard was watching her.

“Unrecognized in museum collections?” he asked.

Rankle said, “Zohn thinks he’s interested in museum studies.”

A good-natured booming filled the space under the tarp and bowled Rankle’s condescending remark cleanly out into the desert. “I am interested in museum sciences,” Rory laughed. “And I’d like to know what to keep an eye out for, since I’ve got an intern-fellowship starting next fall at the Ashmolean. The Tradescant Collection must be full of unsecured antiquities.”

“Exactly; it’s one of Avsa’s favorite places to dig for them,” commented Wayfarer, “Oxford is within easy range of the Szeringka Institute… you may run into her searching for things.”

“Like what kinds of things?”

Wayfarer shrugged. “Like spoons,” she said, holding hers up, “for instance.” The professor knew the word spoon was usually good for a laugh, and the students obliged.

“I mean that fairly literally,” she told them. “Spoons have been around for millenia. It’s just the sort of thing that might show evidence of cultural personalization, or a declaration of ethnic association. It’s not uncommon for cultural cohorts without a dedicated homeland to maintain their social, ethnic, religious, or ancestral identity in their implements of daily life.” This didn’t seem like something she should need to explain to this group, in this place.

“You’re looking for a personalized spoon?” asked the wasp-stung undergrad. The maroon welts on his neck clashed with his bright blue Oriental Institute tee shirt, its white Achæmenid winged lion design cracked and sun-faded, and full of tiny holes at the letter-edges.

His tenacity made Wayfarer smile. “What’s your name, son? Well, Eric, perhaps not actually a spoon. But I would start by looking for an object with an identifying mark, a distinctive and perhaps unexpected characteristic.” Years of teaching had shown her that if you wanted students to understand, you had to speak their language. “A logo, if you will: like on your tee shirt. It could be a symbol, or a character, something that sets it, and its owner, apart from the neighbors. In fact you could say,” she wound up thematically aptly, “that we’re looking for an object like everything else around it, but not quite. As someone who studies language, I might say, an artifact with an accent.”

Rankle interrupted this lesson pragmatically. “Well, the generator goes off at nine pm sharp, so if you’d like to see your little unsecured antiquity in the light, you’d better do it soon.”

There were a dozen or so pairs of eyes on her. It didn’t seem as if this day was ever going to end, but Wayfarer stood up. “By all means,” she said, “let’s have a look.”

to end, but Wayfarer stood up. “By all means,” she said, “let’s have a look.”

To be continued…

To read Part 4, “The Unsecured Antiquity”, click here.

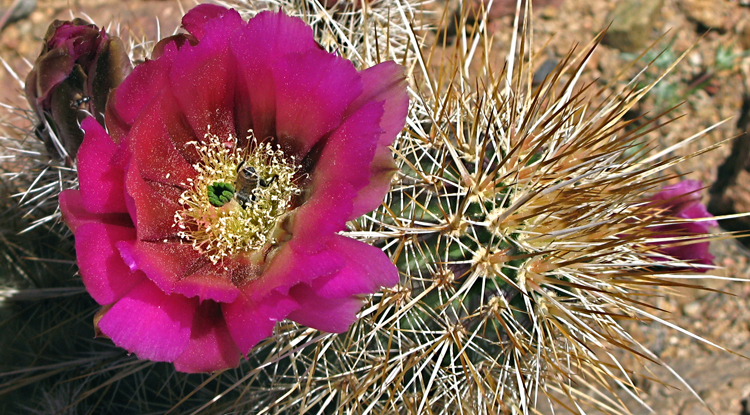

Buckhorn Mountains NW of Phoenix is the spring wildflower bloom. This past weekend the succulent plants predominated: Ocotillos were in full swing, and the prickly pear were starting to get the hang of it.

Buckhorn Mountains NW of Phoenix is the spring wildflower bloom. This past weekend the succulent plants predominated: Ocotillos were in full swing, and the prickly pear were starting to get the hang of it.

most of the year. But their pink-to-magenta flowers are up to three inches across, making flowering cactus stand out on the most brutally exposed slopes of rocky hills and arroyos. <<

most of the year. But their pink-to-magenta flowers are up to three inches across, making flowering cactus stand out on the most brutally exposed slopes of rocky hills and arroyos. << they’re happy baking in the full Arizona summer sun, and can thrive in a crack in solid rock that even a rock wren would scorn.>>

they’re happy baking in the full Arizona summer sun, and can thrive in a crack in solid rock that even a rock wren would scorn.>> << One hog we found had the hugest flowers I’d ever seen: that’s E‘s man-sized palm for scale, not my girly-paw.

<< One hog we found had the hugest flowers I’d ever seen: that’s E‘s man-sized palm for scale, not my girly-paw. right next to the apple-green pistil, which hasn’t opened fully into its star-shaped ærial panoply. You can also see the formidable armory of spines on the fleshy, water-hoarding stems. Even javelina are discouraged by them, although I’ve seen otherwise imposing boar javelinas with lips daintily reddened by the petals of the flowers of a “claret cup” hedgehog cactus. This petal-snacking would be considered hog-on-hog predation, except that neither javelina nor hedgehogs are actual pigs.

right next to the apple-green pistil, which hasn’t opened fully into its star-shaped ærial panoply. You can also see the formidable armory of spines on the fleshy, water-hoarding stems. Even javelina are discouraged by them, although I’ve seen otherwise imposing boar javelinas with lips daintily reddened by the petals of the flowers of a “claret cup” hedgehog cactus. This petal-snacking would be considered hog-on-hog predation, except that neither javelina nor hedgehogs are actual pigs.

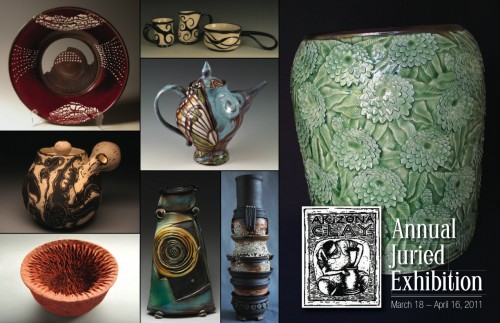

Allison does not consider herself a wildlife artist,

but an observer who takes notes in clay.

Allison does not consider herself a wildlife artist,

but an observer who takes notes in clay.