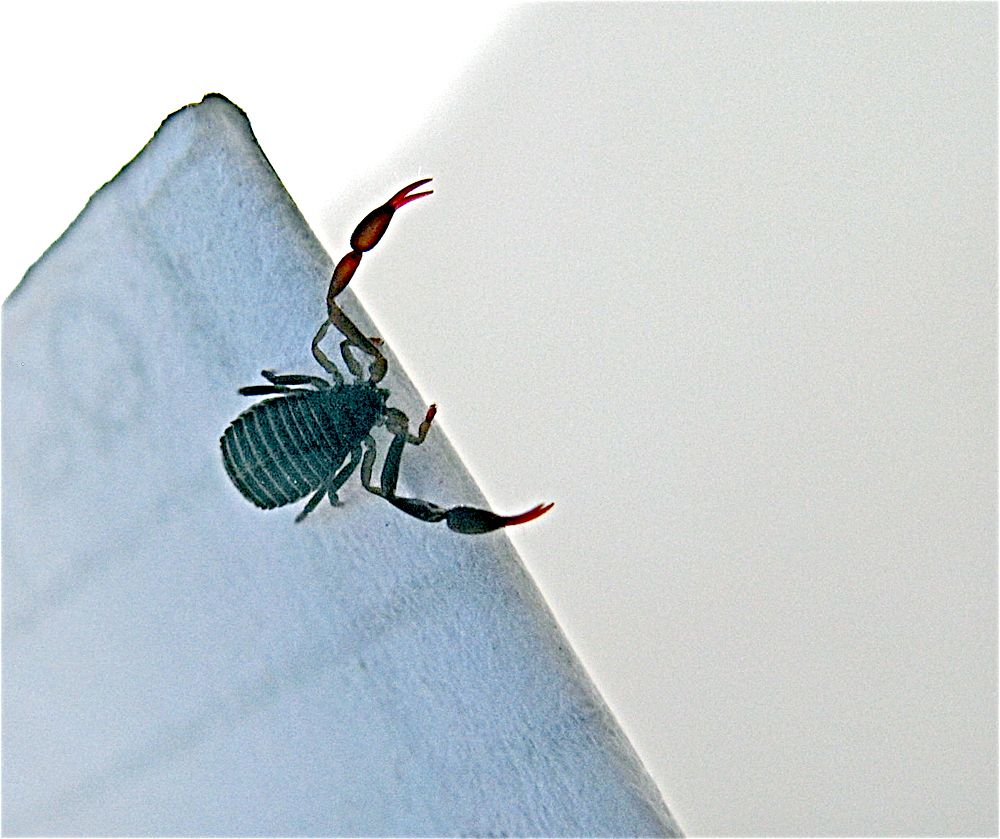

……………………………..or a scorpion!

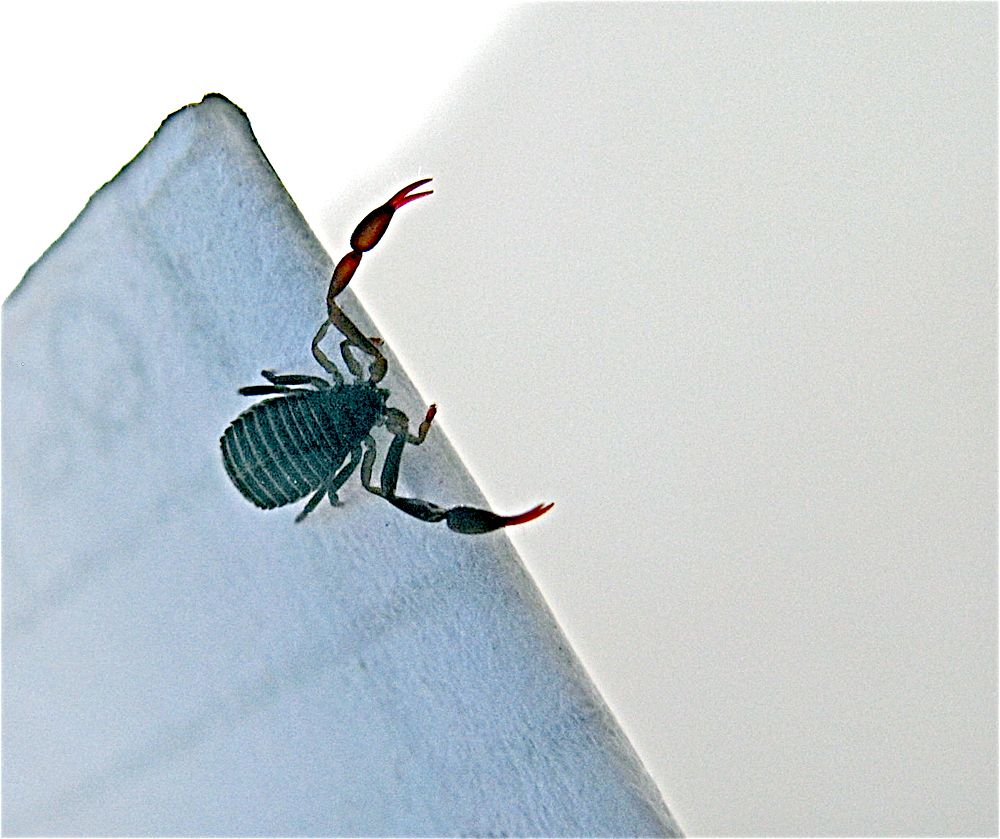

Fear me only if you are a springtail, or a mite, or any arthropod smaller than me. I am the size of a lentil, so although my scissor-like pincers look fierce and outsized for my body, and the pedipalps wielding them are Popeye strong and elbowy, you are a looming threat — I run from the shadows of your hands, and the clicking black boxes you hold over me, by scuttling rapidly backwards across the  exposed surface you expect me to sit still on. I am the pseudoscorpion, an arachnid, little cousin to spiders, solpugids, and amblypygids.

exposed surface you expect me to sit still on. I am the pseudoscorpion, an arachnid, little cousin to spiders, solpugids, and amblypygids.

<< me, much larger than life on the folded edge of a piece of regular paper (photo A.Shock)

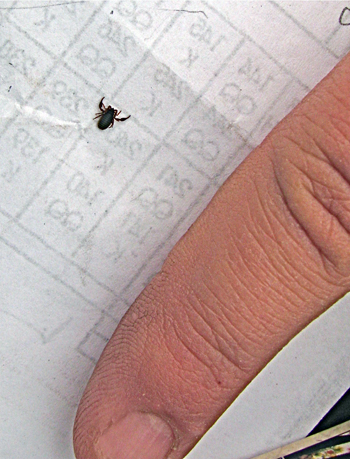

My family and I are tiny predators found all over the world who, if you must use your own reference point to validate us, beneficially snap up even tinier creatures which, grown larger, might trouble you: newly hatched mites and ticks, for instance (they’re cousins, too, and I certainly enjoy that branch of the family, if you catch my drift). Usually I go contently unnoticed, but this past weekend I found myself exposed to sunlight, spied by thumb-mammals who were trying to pack up a buffet they’d set up for me in the pine dirt on the roof of Arizona (they called it a tent and slept in it, which is rude: I don’t doze on their dinner plate). I had been grazing all night on minute leggy snacks that also wandered up from the forest floor onto the buffet — admittedly, stuffed to the spiracles (it was a plentiful spread!), I was a little muddled and got lost in the folds and channels and couldn’t find my way down by sunrise.

They picked me up — I swear they were about to crush me as a loathly tick, but the next thing I knew they had carried me over to their table where they held me captive for a while, which made me alternately freeze  hoping they wouldn’t see me, and flee, which didn’t work either. So I kept waving my pincers at them until no doubt fearful of my ferocious aspect, they put me back in the needles and dirt, and I went on my way.

hoping they wouldn’t see me, and flee, which didn’t work either. So I kept waving my pincers at them until no doubt fearful of my ferocious aspect, they put me back in the needles and dirt, and I went on my way.

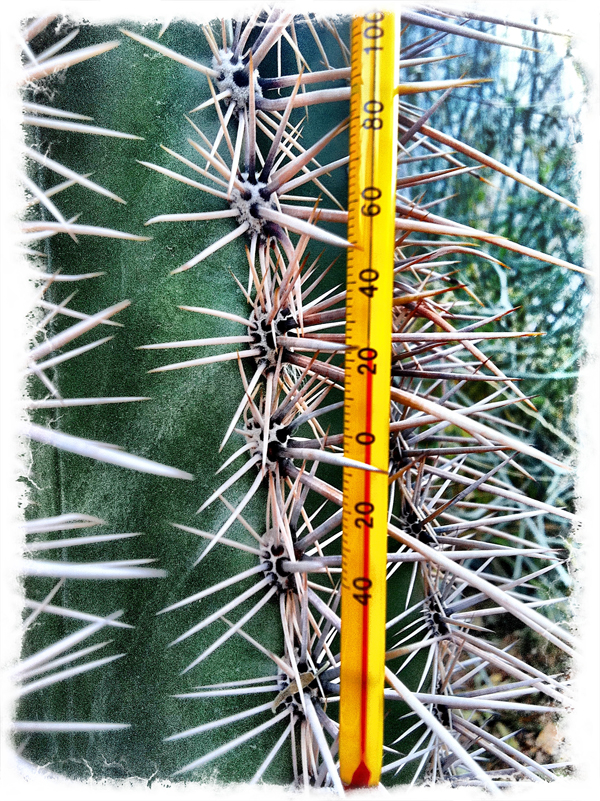

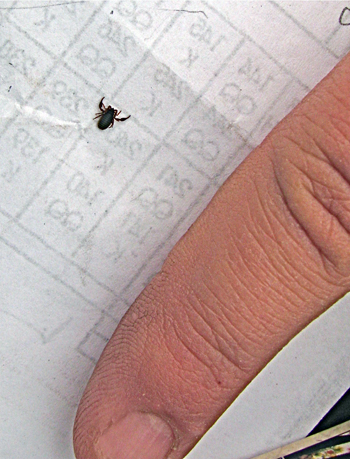

<< their idea of scale

my idea of scale >>

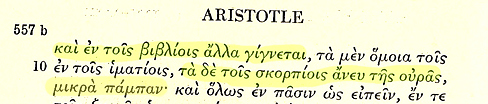

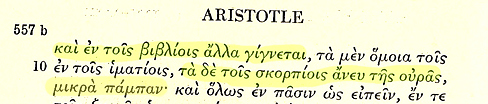

You may never have seen or even heard of my family, but we’re numerous and famous. We’ve been around since the Devonian; that’s 380 million short years, O Primate — fossils attest to that. Note my efficient body design: NOT “primitive,” please — why improve on perfection? But you seemed to notice us, or care enough to write about us, only since the time of Alexander the Great. Please don’t look so surprised, of course we know about him — pseudoscorpions have lengthy ancestral memories. My 2347-times-great grand-cousins inhabited Alexander’s libraries and kept them free of booklice, dust-mites, and silverfish larvae (no doubt King Darius’s libraries, too; we’re the Swiss of the Arthropoda). Anyway, Alexander’s elementary school teacher, who always had his nose in papyrus scrolls, spared a few words for us and some cousins (who live in clothing and keep them free of moths and other undesirable animalcules, unless he’s referring to lice, which are the undesirable animalcules). Wait, I have his famous quote about us by heart:

Oh, you need a translation? Allow me, it’s easy Greek: “Still others occur in books: some like those in mantles, others like scorpions without tails, totally small…” That’s us. Then there’s some stuff about fig wasps… he goes on and on about them; those Greeks do like their figs. Anyway, you see? a shout-out from Aristotle — not too shabby!

So how do we get into your books, or for that matter, high up into the mountainous roof of Arizona? That is a prized family trait — some of us are phoretic. (Honestly, the high-falutin’ term shouldn’t surprise you, didn’t I just quote Greek?) It means we hitch rides on larger organisms, like flies or wasps, and let them  carry us around for a while before dropping off (pincers again: very useful things for gripping as well as dining).

carry us around for a while before dropping off (pincers again: very useful things for gripping as well as dining).

<< a pseudoscorpion latched onto a fly thigh (photo by Sarefo, Wikimedia Commons)

We may be commensal, but we’re not parasites: other than a little drag on our ride’s flight efficiency, we do no harm, and it’s a great way to get around to greener, or rather, more joint-leggedy pastures. And you don’t notice, but we cling to the underside of firewood or potted plants you bring inside from the garden. From there, it’s just a hop scuttle and creep into your woolen carpet (lots of yummies there!) or bookshelf. You’d have nothing left to wear or read if it weren’t for us. A slight exaggeration, perhaps, but without doubt we are excellent guardians against hungry woolen moths, carpet beetle and other dermestid insect larvae, not to mention our less human-centered roles in natural ecosystems: we are leopards on the Serengeti of small-scale soil horizons — though you may need magnifiers to detect our depredations, or to count the legs of our prey.

There’s so much more — I haven’t even told you about our ability to weave protective silken cocoons for ourselves or our offspring by spinning them from spinnerets at the tips of our chelicerae, or that some of us dance elaborate dances before spermatophore transmission (not that that’s any of your business), or that we’re relaxed regarding the concept of eyes, having one pair, two pair, or none at all, or that there are more than three thousand species of us, some limited to single cave sites, others making their living in giant saguaro cactus. But I suspect I’ve bent your ear enough on the efficiencies and curiosities of my large and ancient family. So, here are a couple of websites (yes, that’s arachnid humor) you can visit, borne there on the underside of your computer’s elytra:

visit, borne there on the underside of your computer’s elytra:

For excellent photos click here, for more in-depth info click here, and for those with inexhaustible curiosity about the order Pseudoscorpionida (thanks for noticing, you free-thinking Prussian, Herr Doktor Haeckel), click here at this excellent resource, or here at our Wikipedia entry.

It’s been nice chatting, but there are collembolids to collar and amphipods to ambush. And digest. Have a nice day, and please don’t bother to dust. Really.